Revolutionary cinema: ranking the 10 greatest Italian neorealism movies

Posted On

Posted On

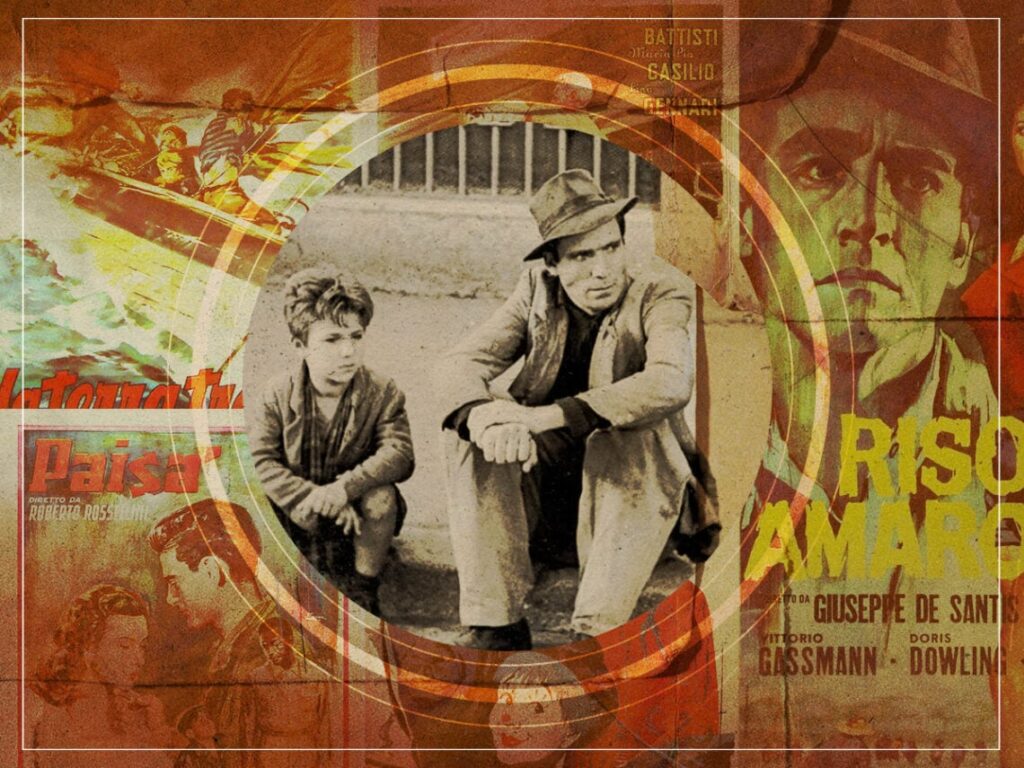

(Credits: Far Out / BFI / Original Promo)

When we think of cinema, the first thing we often think of is the Hollywood studios that make such juggernaut franchises as Marvel, Fast and Furious and James Bond, but such movies are often made cynically with profits purely in mind. On the opposite end of that spectrum is the Italian neorealism movement of the 1940s and 1950s, a cinematic ideology that protested generations of social oppression.

For decades leading up to the start of the Second World War, the cinema industry in Italy was tightly regulated by the government, with Telefoni Bianchi movies, which promoted the prosperity of the country, being the sole type of film being made. Yet, these films simply didn’t reflect the reality of contemporary Italy, with the struggles of the poorest people being seemingly ignored by those in power.

Yet, change came toward the end of WWII when the Fascist rule of Benito Mussolini came to an end, and Italy was forced to identify itself in an entirely new frame of existence. Neorealism was the cinema that was born from these ashes, with the movement being a cinematic protest against everything that had come before it, focusing on the real struggles of those who had been hit hardest by the war.

Dedicated to realism above all else, these movies tackled the troubled morals of a country wrestling with its own identity, with the very best films of the era coming from such pioneers as Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica and Luchino Visconti.

The 10 greatest Italian neorealism movies:

10. Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946)

Vittorio De Sica might have started his filmmaking career by making Telefoni Bianchi movies, but it only took a few years for him to become a master of Italian neorealism. It was Shoeshine, released in 1946, which helped him achieve this status. The film is widely considered one of the earliest examples from the movement, and it was incredibly successful, too, winning an honourary Oscar as well as a nomination for ‘Best Original Screenplay’.

Shoeshine follows two young boys working as shoe shiners, attempting to save up the little money they make to buy a horse. The pair end up getting in trouble with the police, resulting in them being sent to a juvenile detention centre. Despite the actors being non-professionals, they deliver incredible performances for De Sica that highlight the realities of growing up under economically challenging circumstances.

[embedded content]

9. Germany, Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948)

While most Italian Neorealist films take place in Italy, Rossellini used Berlin as the setting for Germany, Year Zero, released just three years after the end of World War Two. Yet, the filmmaker utilised the same techniques that made his other works, like Rome, Open City, so good – capturing the bleak realities of a country devastated by war. He also used a child as his protagonist, in keeping with Neorealist tradition, although he deals this young child a particularly cruel fate.

The movie is easily one of the bleakest of the movement, with the main character, Edmund Köhler, witnessing his father’s health rapidly deteriorating. When Edmund is reunited with an old teacher, a Nazi, he finds himself under the influence of his twisted beliefs, carrying out a heinous act that he thinks will make him seem like a hero. Rossellini didn’t hold back when he made Germany, Year Zero; it’s a tough watch with the power to haunt your mind long after watching it.

[embedded content]

8. Il Grido (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1957)

Michelangelo Antonioni is one of the few Italian neorealism directors whose style and influence allowed him to excel outside the borders of his own country, making such celebrated European films as Blow-Up in 1966 and The Passenger in 1975. Before such movies, however, he was considered one of neorealism’s most influential voices, helping to lay the foundations of its form with Il Grido in 1957, a film which follows a man’s aimless wander away from his responsibilities.

Leaving the love of his life and the town he holds dear to his heart, Il Grido spoke to the symptoms of so many lost individuals in post-war Italy who simply wished to walk away from their problems to discover new pastures. A beautiful and deeply haunting piece of cinema, Il Grido might be one of neorealism’s most poetic offerings, giving viewers something that better resembles arthouse poetry rather than documentary-like realism.

[embedded content]

7. Bitter Rice (Giuseppe De Santis, 1949)

One of the main reasons the Italian neorealism cinema movement emerged was that film critics Giuseppe De Santis and Luchino Visconti rejected the kind of cinema they were being forced to watch throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. Both these critics later put their cinematic knowledge to the test; however, they turned their attention to filmmaking and made such classics as 1948’s The Earth Trembles and 1949’s Bitter Rice in the process.

A low-tempo crime movie telling the story of two criminals evading the law who decide to work in a rice field while trying to recruit new members into their gang, Bitter Rice was a key neorealism text, accurately reflecting the realities of rural workers in Italy. Also pioneering in its commentary on sexuality and gender roles, Bitter Rice was, thematically, one of the most revolutionary films of the era.

[embedded content]

6. La strada (Federico Fellini, 1954)

Federico Fellini isn’t usually one of the first people to come to mind when we think of Italian neorealism since most of his popular works deal with fantasy and dreams. Yet, several of his earlier films, such as La Strada, are considered part of the movement, although they emerged as it was beginning to die out. Still, Fellini brought a unique vision to this period in Italian cinema with La Strada, bridging the gap between neorealism and the fantasy themes which would define his later films.

Thus, La Strada isn’t as bleak of a tale as Germany, Year Zero, for example. The film sees a woman named Gelsomina embark on a journey with a strongman, who teaches her various tricks to perform so that she can earn money for her poor mother. Fellini highlights the way that poverty can force people to go to extreme lengths to earn money, but through Gelsomina’s eyes, he asserts that no matter your situation, there is always an opportunity to find beauty in the everyday. The film isn’t all whimsical, though – there are plenty of tough moments which keep it firmly grounded in realism.

[embedded content]

5. Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1952)

Before De Sica started to move away from Italian neorealism, he made Umberto D., naming the titular character after his own father. The movement started to fade out in the early 1950s, but before its flame was snuffed, De Sica proved that there was time for him to make another masterpiece. Starring Carlo Battisti as Umberto, we witness his attempts to stay afloat in the face of poverty. Struggling to find enough money to pay rent because of his measly pension, Umberto sells his things, but regardless, he finds himself stuck in a less-than-desirable position.

Eventually, Umberto feels so hopeless that suicide seems like his only option, although he must find someone to take care of his loyal dog, Flike, first. While the movie deals with some bleak themes, it’s not a strictly depressing watch. Rather, De Sica highlights the power of human connection and companionship as a saving grace. There are many heartwarming scenes, particularly those between Umberto and Flike, which give the film its charm and warmth.

[embedded content]

4. Paisan (Roberto Rossellini, 1946)

Another film from, arguably, the definitive master of neorealism, Roberto Rossellini, many consider 1946’s Paisan to be the director’s masterpiece. A hard-hitting war movie that delves into the existential realities of so many in post-war Italy, the film tells the story of American soldiers pushing through the country in attempts to drive out German forces, with every new mile of ground bringing them face to face with locals who were once the enemy.

One of the simplest yet most emotionally complex movies of the neorealism movement, Paisan has since become a favourite of arthouse lovers across the world. A great influence on the great Martin Scorsese, whose four grandparents were Italian immigrants, the director said of the film: “I was experiencing the power of cinema itself, in this case, made far beyond Hollywood, under extremely tough conditions and with inferior equipment… I was also seeing that cinema wasn’t just about the movie itself but the relationship between the movie and its audience.”

[embedded content]

3. The Earth Trembles (Luchino Visconti, 1948)

Too often forgotten when it comes to the very best movies of the Italian neorealism movement, The Earth Trembles from Luchino Visconti is a powerhouse of filmmaking. One of the most authentic neorealism films there is, Visconti’s drama tells the story of fishermen in Sicily who strive to take their business independent after having struggled under the weight of capitalist wholesalers for years. Speaking directly to the values of the cinematic movement, The Earth Trembles is championed by academics as being the quintessential neorealist film.

Giulia Saccogna, the programmer for the BFI’s latest Italian Neorealism season, stated about the movie: “La terra trema as possibly the purest example of neorealism with its whole cast of non-professional actors, speaking their local dialect, and the compositional rigour of each frame that gives the film an ecstatic beauty.”

[embedded content]

2. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

Just two years after Shoeshine, De Sica made what is considered by many his magnum opus, Bicycle Thieves. A classic entry to the Italian neorealist film movement, the film follows a poverty-stricken man, Antonio, and his young son, Bruno, as they embark on a journey to find Antonio’s stolen bicycle. After pawning the family’s prized possessions in exchange for a bike, Antonio’s new mode of transport is stolen while he’s working on a ladder, leaving him to chase after the thief to no avail.

With Bruno in tow, the pair do all they can to retrieve the bicycle. Antonio desperately needs it so he can provide for his family, which includes his wife and newborn baby. While the film was received rather negatively in Italy because of its honest portrayal of working-class citizens neglected by the Italian government, it received much greater praise abroad, even receiving an Academy Award. Bicycle Thieves is a tender and heartfelt film, yet one that doesn’t hide the harsh realities of post-war Italy.

[embedded content]

1. Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

For an art movement that was born from the hardships of wartime, Roberto Rossellini’s 1945 release Rome, Open City is the most essential film of the lot, pioneering a way forward for many directors to come. A raw recount of the social deprivation of the country in the final years of the war, Rossellini’s film tells the story of a resistance leader in Rome who desperately evades the Nazis while Italy is under German occupation.

Calling the film the best place to start when it comes to Italian neorealism, Saccogna further added that the film “was a transitional film for a society coming out of 20 years of fascism, an essential testimony of the German occupation of the capital made at a time when Germans still occupied the North of Italy”. To watch Rome, Open City is to see the social and political spark that triggered the protest of neorealism. There is truly no other film like it.

[embedded content]

Chasing the Real: Italian Neorealism is at BFI Southbank from May 1st – June 30th, with selected films also available to watch on BFI Player.

Rome, Open City is re-released by the BFI in selected cinemas, from May 17th.

[embedded content]