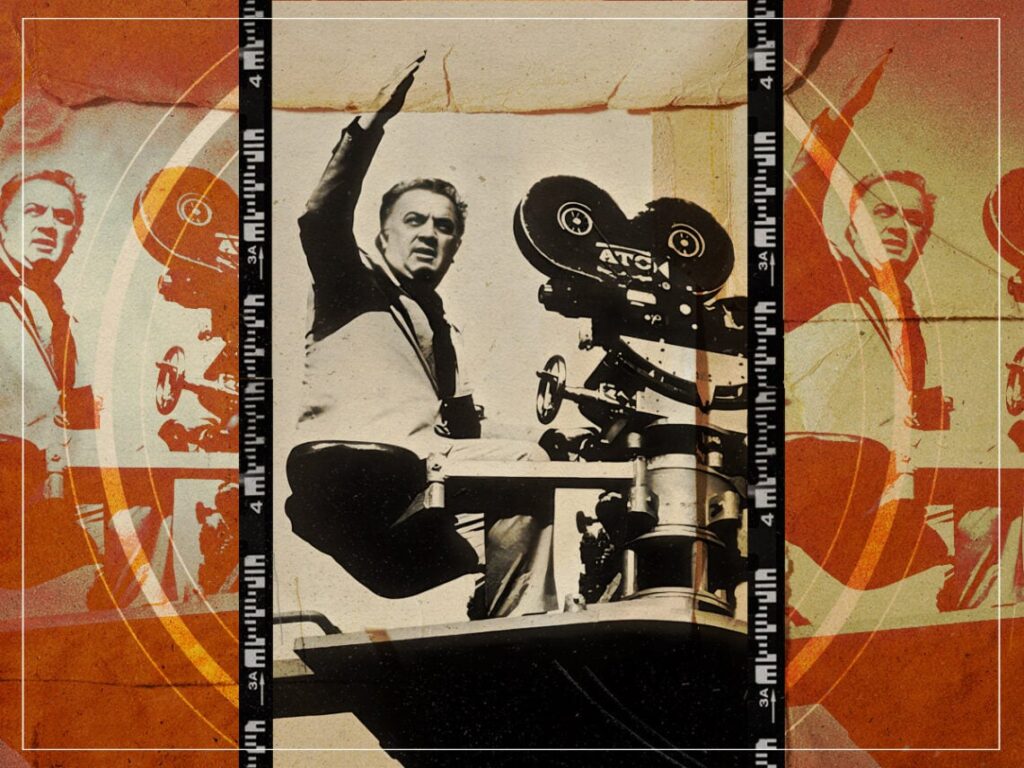

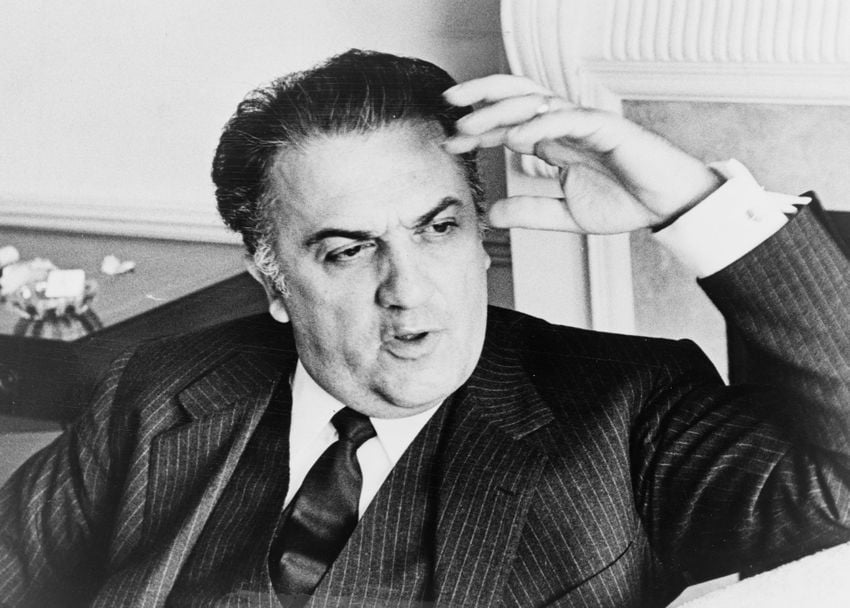

Federico Fellini: The neorealist roots of Italy’s greatest director

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

In few places throughout the course of the mid-20th century was an artistic resistance to the onslaught of fascist socio-politics felt more than in Italy. As the grip of Benito Mussolini’s regime tightened on the country, the Italian film industry was largely dominated by studio-led productions that falsified the well-being of its inhabitants, but the moment that Mussolini’s censorship on the arts somewhat loosened, the most prominent Italian directors of the 1940s and 1950s were on hand to shake up the cinematic medium.

In 1943, the Italian neorealism movement was born with Luchino Visconti’s film Ossessione, which used non-professional actors, shot on location and detailed the harsh realities of life under a fascist dictatorship. Neorealism suddenly became the favoured artistic mode of address in Italian cinema, with the likes of Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica using the blueprint that Visconti had championed.

The aforementioned directors would all go on to become some of their country’s most acclaimed cinematic artists, but few enjoyed the universal acclaim of their fellow countryman Federico Fellini, who would later become known for his surrealistic portrayals of human life with La Dolce Vita and 8½, leading to a reputation as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of all time.

Fellini’s beginnings as a director, though, are inextricably linked to the Italian neorealism movement, and though he is not as closely associated as the likes of Visconti, Rossellini et al., he is undoubtedly responsible for its overall development, having worked with some of the movement’s most prominent figures and also having produced at least a handful of works under its artistic guidelines.

The future director was born in Rimini in 1920, and his relatively humble early days on Earth provided a socio-political understanding of the world that would pay dividends in his treatment of class in his future films, despite his overall apoliticism. At school, Fellini became a member of the Avanguardista, the compulsory fascist youth organisation of Italy, which also informed the young man of the realities of Mussolini’s ongoing propagandist regime.

After supposedly studying at law school in Rome (where no actual records exist) and briefly working as a journalist, Fellini found a penchant and skill for comedy, and he began writing for the biweekly humour magazine Marc’Aurelio, which invariably led to later opportunities in the film industry. As the 1940s came into fruition, Fellini was writing sketches and jokes for radio and film productions, and after narrowly avoiding the World War II draft, he began an apprenticeship of sorts, in line with the neorealism movement, that coincided with the Allied liberation of Rome.

Roberto Rossellini had met Fellini in a shop where the latter had been drawing caricatures of American soldiers, and it was at this point that Fellini’s credentials as a proponent of neorealism were borne. At the time, Rossellini had been working on what would become Rome, Open City – often considered one of the greatest Italian neorealism works of all time – and Fellini was employed by the director to write some gags and a few scenes of dialogue for its screenplay. Fellini would duly go on to be nominated for the ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’ Academy Award in 1947 for his work on Rossellini’s film.

Having established himself as a screenwriter on Rome, Open City – plus a handful of previous films including Before the Postman, The Peddler and the Lady and The Last Wagon – Fellini continued his journey into neorealism with Rossellini’s Paisa while also beginning his collaboration with another of the movement’s key figures, Alberto Lattuada, with whom he worked on Flesh Will Surrender, Without Pity and Il mulino del Po. Before long, Lattuada would grant his peer his first co-directing opportunity with 1951’s Variety Lights, marking the end of his apprenticeship and the start of the remainder of his professional life.

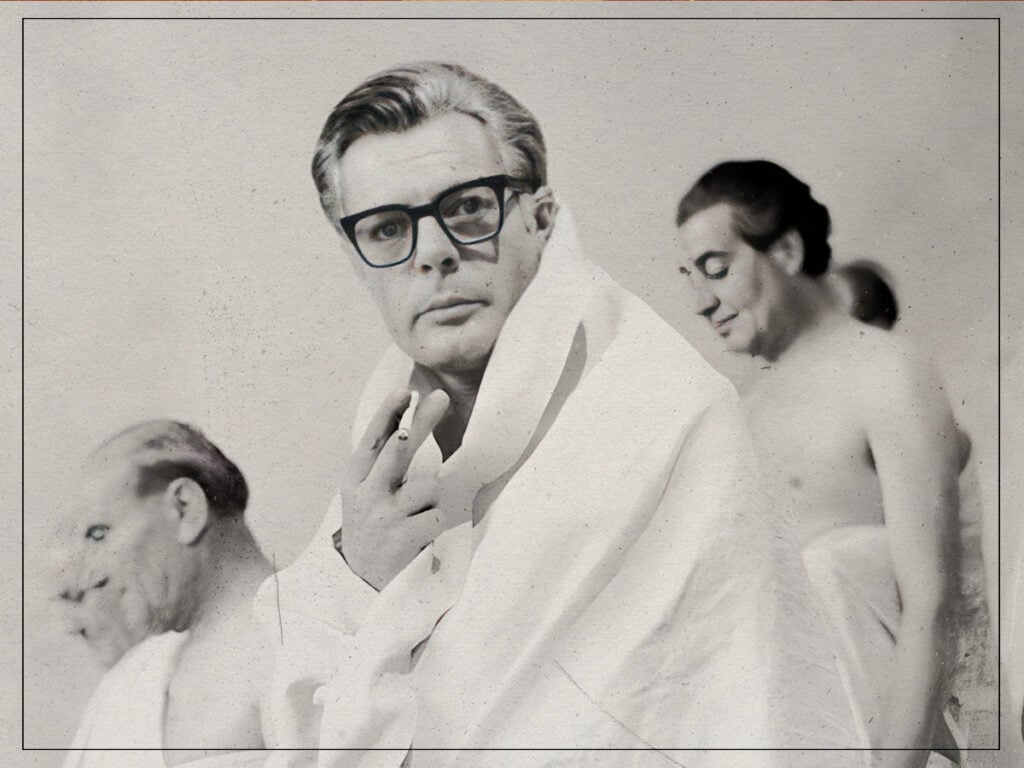

Variety Lights tells of a young woman who joins a struggling vaudevillian troupe, which results in a growing sense of jealousy and bitterness among the players, and the emotional honesty and narrative authenticity on display in the film would come to influence Fellini’s own works of the future. A year after Variety Lights’ released, Fellini delivered his first solo directed feature film in the shape of The White Sheik, which also undoubtedly delved into the traditions of neorealism.

The romantic comedy, starring Alberto Sordi and Leopoldo Trieste, focuses on a man who brings his new wife to Rome for an audience with the Pope and to meet his family. However, when the bride runs away to find the hero of her favourite romance novel, the man must desperately explain her disappearance. The comic exaggeration of The White Sheik would help to broaden the appeal of the neorealist movement, which had tended to be a righteously dour affair, though with good socio-political reason.

Still, the kind of downtrodden narratives that the Italian neorealism movement was defined by could still be found in the early works of Fellini, at least up until his 1960 film La Dolce Vita. In I vitelloni, La strada, Il bidone and Night of Cabiria, Fellini provided the stories of the most marginalised members of society, who were often found in littered and largely deserted Italian environments, either rural or urban.

Take, for instance, the five small-town male protagonists of I vitelloni, the sex-working female main character of Nights of Cabiria, or the strange relationship between a strongman and simple-minded woman in La Strada, each of which proves Fellini’s neorealist insistence on documenting the harsh realities of life in post-war Italy, just as the likes of Rossellini and Visconti had done in the years prior.

However, it ought to be stressed that Fellini’s films mostly tap into the aesthetics and themes of neorealism rather than serving as some of its most direct examples. Instead, Fellini had imbued his early works with an air of comic surrealism that would come to define the most significant period of his professional life as a director, straying somewhat from the direct storytelling of some of the movement’s most prominent forbears.

As the Italian neorealist movement wound down towards the end of the 1950s, Fellini, like many of his fellow directors of the time, departed the movement to create his own unique style of film, most notably in the shape of La Dolce Vita, 8½, and Satyricon, and his acclaim and stature as one of Italy’s greatest ever directors continued to expand.

So, while it would be hard to argue that Fellini is one of the most significant figures in Italian neorealism, it’s undeniable that his early works greatly contributed to the overall importance of the movement. Fellini’s early neorealist phase showed a director with a fascination with the most authentic mode of storytelling, which would undoubtedly inform the rest of his directing career, and a desire to disrupt the fascist censorship of cinema with moving stories surrounding the outcast and downtrodden members of post-war Italian society.

Chasing the Real: Italian Neorealism is at BFI Southbank from May 1st – June 30th, with selected films also available to watch on BFI Player.

Rome, Open City is re-released by the BFI in selected cinemas from May 17th.

[embedded content]