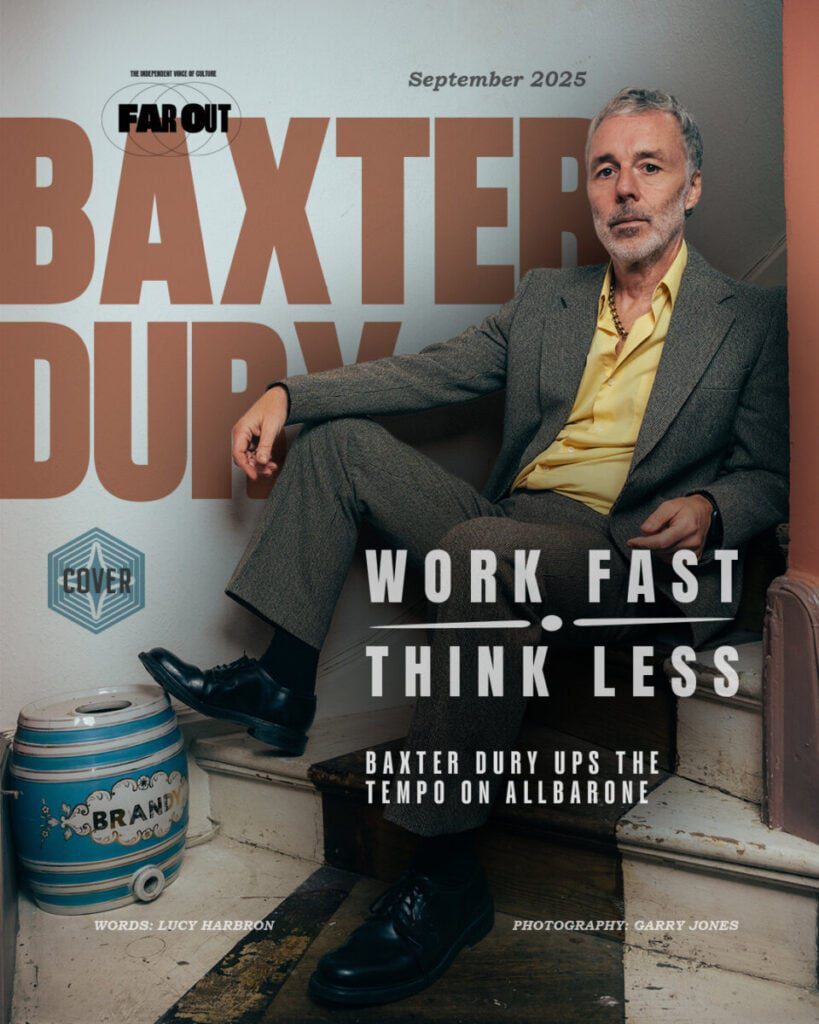

Work fast, think less: Baxter Dury ups the tempo on ‘Allbarone’

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Garry Jones)

Teachers at school like to tell us that the walls are blue because the author meant something by that. Baxter Dury has spent eight albums pretending that’s true. On his ninth, he decided to stop.

“You know, when we talk about songwriting and stuff, and they go, Well, this and that, and what does it mean? I go, I don’t fucking know,” Dury admits at the very end of our conversation, “I sort of grab at stuff, and some of it’s real and some of it’s not. I mash it all up, and as long as no one gets too offended, I sort of censor it, and then I put it out there.”

That’s the writing process that very few other artists would own up to. As for the blue curtains and the childhood lessons that they surely represent something bigger, he’s fucked that off; “Actually, no, they don’t mean that,” but he qualifies for a second, “Probably some psychopathic writers definitely do.”

Yet still, my job as a journalist, sitting next to Dury in a pub in Hammersmith, is to paint meaning onto the curtains. I know that, he knows that, and for every album cycle before this one, the game has been played. Here, we both try to ditch it. “What’s really interesting is you write songs like that, and depending on, a lot of time what country you’re in, they’ll totally interpret it in an entirely different way, and sometimes fantastically,” he said, adding, “France, for instance, a very philosophically overindulgent country, will go off on them. And you sort of have to agree, because you don’t know what they’re talking about, and it sometimes makes you look a bit more intellectually robust than you really are.”

For eight albums, Dury has been offering up his work, hearing these readings of it and, by his own admittance, essentially picking the smartest on and adopting it as if that was his purpose all along, that was what he was always getting at, even if he was actually getting at absolutely nothing. That’s fine, though. That’s the lesson making Allbarone taught him – that’s absolutely fine.

The story of Dury’s ninth album doesn’t really begin with him. Instead, it begins with Paul Epworth, the pop master producer behind work from Adele, Rihanna, Florence and the Machine and many more. They’d known each other for a while, but the idea of their two musical worlds colliding seemed alien and incompatible until suddenly it didn’t.

It was Glastonbury 2024. Dury had been touring I Thought I Was Better Than You for what felt like forever, and around as the final song of his set, he played, as usual, ‘(Baxter) These Are My Friends’, his collaboration with Fred Again.

As always, the crowd danced. He always gets them moving throughout the set, but with the permission that a song like that one seems to grant, with its more obvious energy, the crowd always seems to fully commit to it. Each night, he wanted that and loved it, and then suddenly, the idea of a Paul Epworth production didn’t seem so weird.

“Maybe I’d sort of psychologically made him, in his tender state in Glastonbury, ask me the question that I wanted him to ask,” he recalls of the moment, acting it out; “He sort of, in quite a cheesy way, went, ‘We should make music’. And I went, and I tried not to look too excited. I went, ‘Maybe, yes, maybe.’”

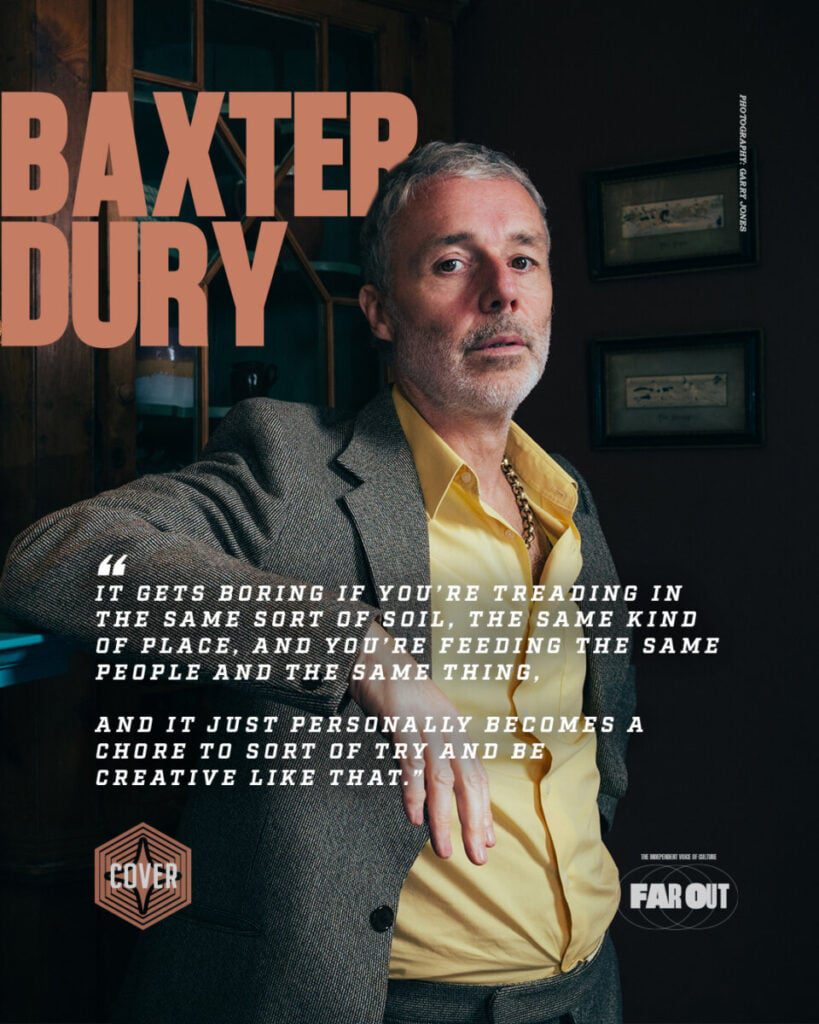

It would have been easy for Dury to produce another album of the same, of what he dubs “cockney, mockney… talking man music”, but he decided to do something different and do it all in a different way.

“It gets boring if you’re treading in the same sort of soil, the same kind of place, and you’re feeding the same people and the same thing, and it just personally becomes a chore to sort of try and be creative like that,” he said, reflecting on the impact of boredom on both maker and listener. Paul Epworth’s job was to essentially force him off that patch of ground.

“I just had someone quite muscular, not in a manly way, but just in a bossy way, a muscular plan-making person that just went, ‘We’re going this way’. And I went, ‘OK, it’s so exciting’. And I sort of followed him, really,” Dury admitted. The sessions for Allbarone all worked on Epworth’s schedule rather than traditionally following his own. Dury would show up at the studio, sit behind the producer as he crafted a sound and sometimes outright ignored Dury’s ideas to keep him off that patch of old-land.

It was tough. “I’m a sort of flappy, bossy dude,” Dury will admit. “I tend to flap and say, We’re doing this and we’re not doing this in an attempt to try and do a song in every version possible. I’ll take it in a bossa nova route and then a reggae route or whatever, and that’s just the way I attempt to exhaust my creative process,” he said about the long way around from which all his previous albums have eventually formed. Epworth didn’t allow that; “He just simplifies it and takes it in the way that he thought was right.”

At the end of their three-hour session, Dury would essentially be handed a track and be set off to write his lyrics as homework with no arguing back, implored to write fast and not think too much. After the first few hours, it became clear that Dury couldn’t play his usual neurotic games. “He went, ‘Yeah, done.’ And I was like, ‘Wow’,” he said as the first sounds of the album played out that day, “Immediately you find a way of working. And it wasn’t always that easy, but essentially I knew it was going to work.”

It was going to work because in the undercurrent of it all, both Epworth and Dury knew what the artist wanted, because they’d both witnessed it that day at Glastonbury during that final song when the crowd started really moving.

“We had a discussion about just upping the tempo of what I did because he saw us play live, and he really enjoyed it, and he thought we could make this go much faster, which sort of naturally goes into dance realms,” Dury said and so really, Allbarone was Dury making an album you can really dance to and roping in a big pop producer to get him out of his head and into that high-tempo mindset where things can be fast and fun and sometimes meaningless as long as they have heart.

And there is still heart here as Allbarone still has all the Baxter Dury-isms fans love and want and expect, from the sharp character commentary to the witty humour and wry one-liners. The point wasn’t to totally be someone else, the point was just to be himself, differently.

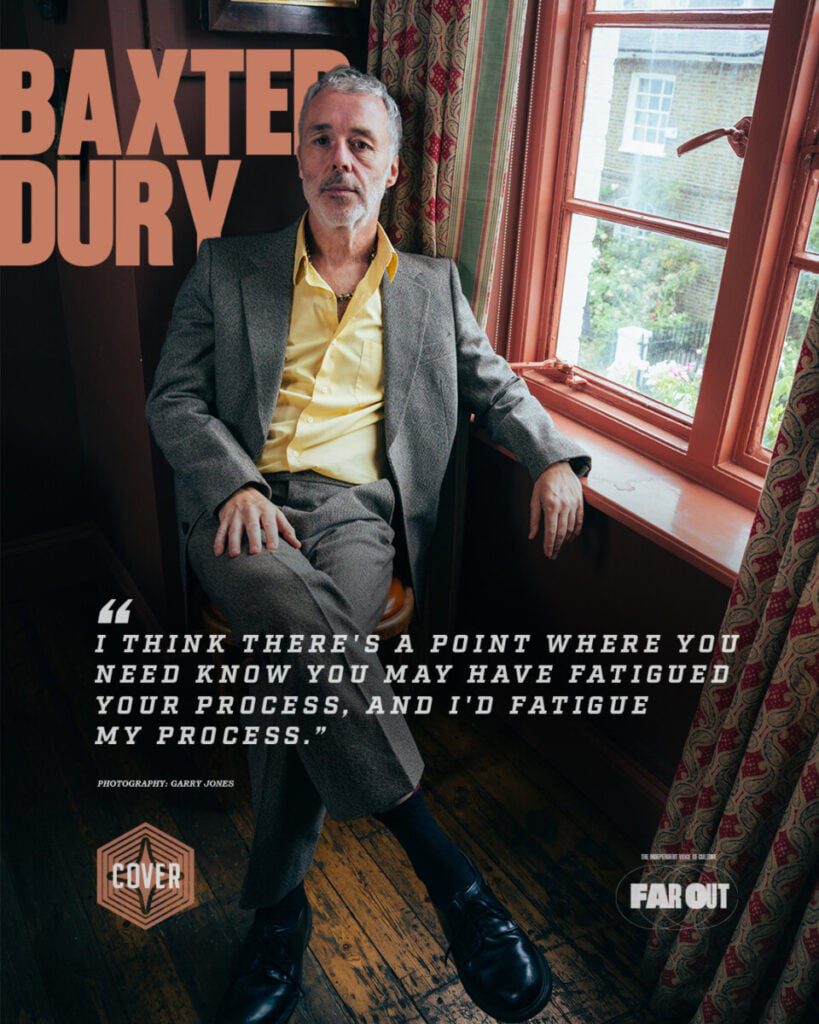

“I think there’s a point where you need to know you may have fatigued your process, and I’d fatigue my process,” Dury said. Tired of the cycle, tired of acting like he meant that smart reading of nonsense, tired of the same-old-same-old, he needed to let loose, and there’s no better way to do that than with a dance in a room where the curtains are blue just because they’re cool, just because the word rhymed or simply, just because.

[embedded content]

Related Topics