Withnail: the portrait of the artist as a lost man

Posted On

Posted On

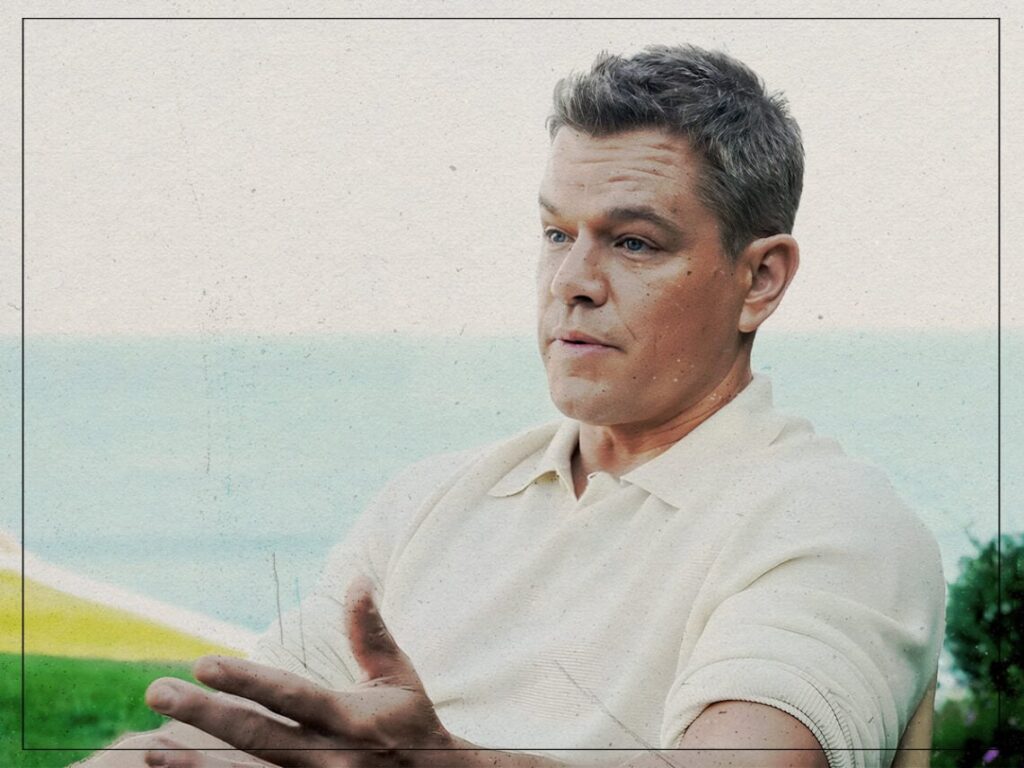

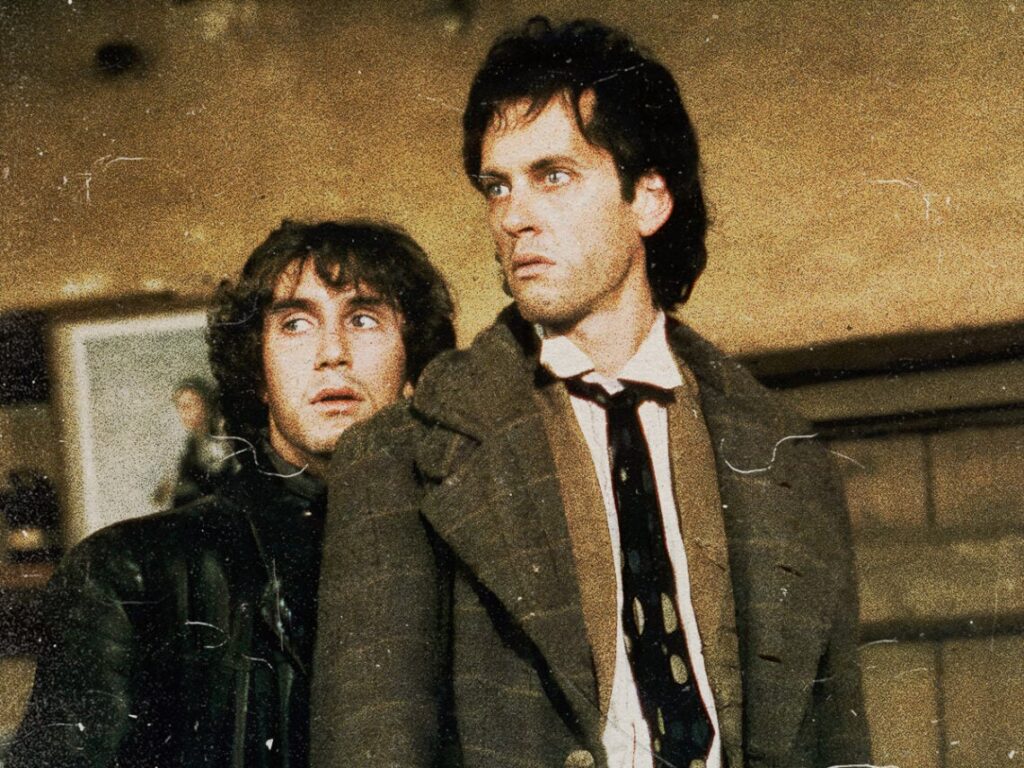

(Credits: Far Out / Handmade Films)

There are so many quote-worthy lines in Bruce Robinson’s 1987 cult classic Withnail and I that it’s harder to find the lines that aren’t iconic than the ones that are. Starring Richard E Grant and Paul McGann as two penniless actors in late 1960s London, it is a downbeat comedy about disillusionment, friendship, and an accidental holiday.

Robinson based the film on his own experience as an unemployed thespian and his friendship with fellow out-of-work actor Vivian MacKerrell. From living in squalor to downing lighter fluid in lieu of liquor, the story is, in many ways, true to life. But it’s Grant’s performance as Withnail that makes the film more than just a string of antics and memorable dialogue.

Withnail was brought up in an upper-middle-class family and had a public school education, but by the time the events in the movie take place, he has become a bundle of contradictions. His voice oozes poshness even as he shouts expletives at passersby while driving around London. He wants the finest wines known to humanity even when he can’t afford beer. He is an actor and a thespian of the first order, but he can’t get a job.

According to Grant, Robinson described Withnail as a “lying, mendacious, cowardly, prancing, posing, utterly charming old darling”. Somehow, the actor managed to make him even more than that. Withnail is undoubtedly misanthropic and selfish. He is overflowing with charisma and theatricality. He feels that the world has dealt him a bad hand despite his privileged upbringing. He is a terrible friend, as evidenced by the fact that he completely ignores Marwood (the “I” of the title) when he is subject to unwanted sexual advances from Withnail’s Uncle Monty (Richard Griffiths).

But he is also a tragic figure, not just a reprehensible one. His willingness to live in a rat-infested flat isn’t just a reflection of his nihilism but proof that he has refused to capitalise on his family’s wealth. He sees himself as an artist, even if no one else – including casting directors – sees him as one. He is lost somewhere between this uncompromising image of himself and the cruel reality that some people don’t get to live their dreams.

When Withnail realises that he and Marwood need to get out of the suffocating gloom of London, he gains permission from Uncle Monty to visit his cottage in the countryside. The digs are even worse there than in London, with constant rain, chilly locals, and no food. They resort to shooting fish from a bridge with a shotgun and shivering in freezing beds at night. Withnail’s romantic idea of a bucolic holiday was just that – an idea. He is supremely unprepared for the realities of the world but would still rather imagine the possibilities and be wrong than prepare himself for the worst. This shameless romanticism is the heart of the character. He may be selfish, sullen, and cowardly, but he is driven by a wild fantasy that he is bound for greater things, be it a weekend of sunshine and fresh air or theatrical glory.

His outlook on life makes him an irreparably lonely figure. Marwood is the closest thing he has to a friend, but, as is evident in the way Robinson described his relationship with MacKerrell, he sees Withnail as more of a character than a confidant, a curiosity who illustrates a finite period of his life rather than a permanent fixture.

At one point in the film, Uncle Monty says something unintentionally prophetic. “It is the most shattering experience of a young man’s life when he awakes and quite reasonably says to himself: ‘I will never play The Dane.’ When that moment comes, one’s ambition ceases. Don’t you agree?” This evocation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet returns in the final scene of the film. Marwood has just learned that he has been offered the lead role in the play and will finally be escaping London for good. He even gets a new haircut to hammer the point home that he is evolving while Withnail, drunk and poetic as ever, remains lost in place. After the two say their goodbyes in Regent’s Park, Withnail staggers to the wolf enclosure at the zoo in a torrential downpour and thunders one of the most famous soliloquies of the play, “What a piece of work is man,” to the animals behind the fence.

Recognising that he has been left behind, he is still willing to “play The Dane,” even if there is no audience to witness him. Withnail embodies the single-minded determination of an artist, even when he is the only one who will ever know he is one.

[embedded content]

Related Topics