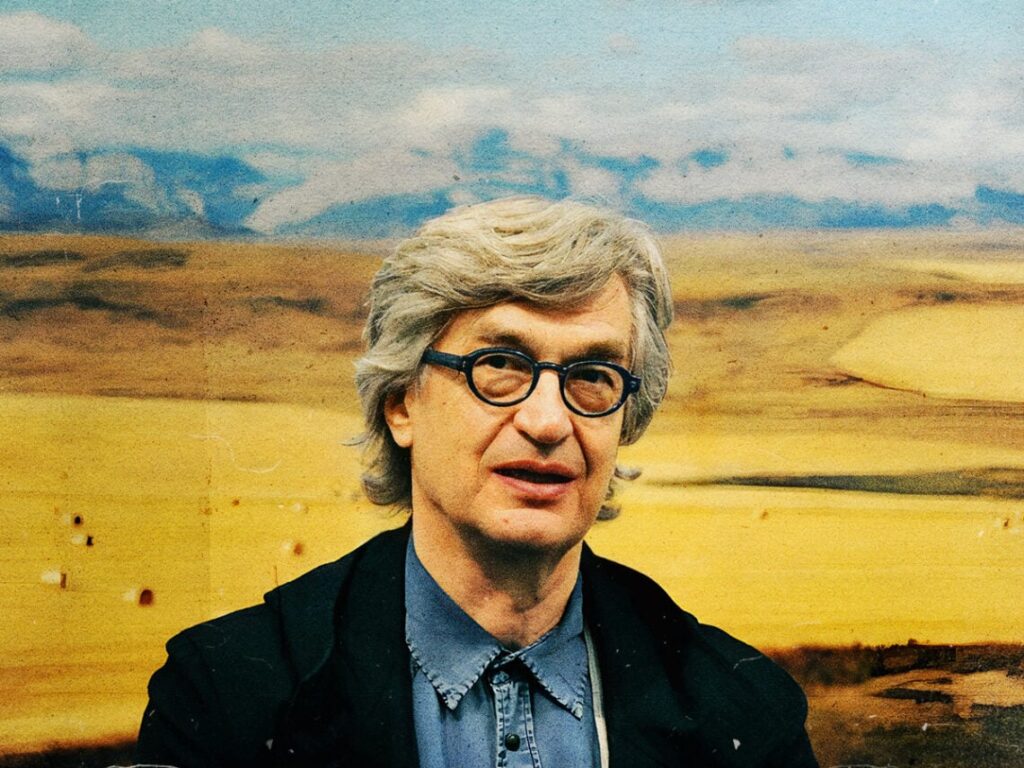

Wim Wenders on how Van Morrison transcended “meanings and definitions”

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

All of Wim Wender’s movies are so beautifully human. He never shies away from showing the breadth of emotions and experiences that make being alive such a complex yet rewarding affair, imbuing each movie with a poetic sensibility.

One of the defining traits of his movies has always been travelling. His exploration of life is reflected in his dissection of transience and the constant sense of change that comes with being on the road. With Alice in the Cities, one of his early road movies, he explores one man’s spiritual and physical journey as he travels from New York to Germany, looking after a child he meets at the airport who he is initially reluctant to care for. With movies like Paris, Texas and Wings of Desire, Wenders continued to interrogate what it means to be alive, further emphasising the pleasures and pains of humanity in the latter by following an angel who desires to become mortal.

Throughout his filmography, Wenders has always prioritised good music, which often plays an integral role in the atmosphere of his films. In Alice in the Cities, Sibylle Baier plays a gentle folk song on a boat, Wings of Desire features performances from artists such as Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and Paris, Texas is anchored by Ry Cooder’s emotive slide guitars. Wenders even directed the documentary Buena Vista Social Club, all about Cuba’s musical history, exploring Cooder’s involvement with the ensemble of the same name.

Clearly, music is hugely important to Wenders and his films, using the perfect tracks to elevate the levels of feeling and humanity in his work to even greater heights. It’s unsurprising, then, that he loves Van Morrison, a musician who has always dug deep into the facets of existence, exploring spirituality, love and nature. His lyrics capture something that feels out of reach to the average person – as if he knows something we don’t. Wenders’ preoccupation with human existence and spirituality (Wenders once told ASX, “It’s [spirituality] driving my work”) seems to, in a way, mirror Morrison’s approach to songwriting.

Discussing Morrison’s songs, Wenders once said: “I know of no music that is more lucid, feelable, hearable, seeable, touchable, no music you can experience more intensely than this. Not just moments, but extended . . . periods of experience which convey the feel of what films could be: a form or perception which no longer burls itself blindly on meanings and definitions, but allows the sensuous to take over and grow . . . where indeed something does become indescribable.”

There’s a visceral quality that Wenders loves, which is a testament to Morrison’s ability to illuminate the human experience through his words. Wenders even made a short film in 1969 about his love of music, 3 American LPs, including Morrison’s ‘Astral Weeks’. Wenders’ love of Morrison started in the ‘60s when the musician was a part of Them. For Wenders, discovering these English-language bands was truly mind-blowing.

He once explained, “These kids, they were ‘my generation,’ just like the Who were saying it. They were just as old as I was, a couple of them maybe a year or two older, and most of them were art students who had invented that music from scratch. I identified with them — that was my own generation, and the music they made was really my music.”

[embedded content]