Why Ingmar Bergman preferred New Hollywood to the French New Wave

Posted On

Posted On

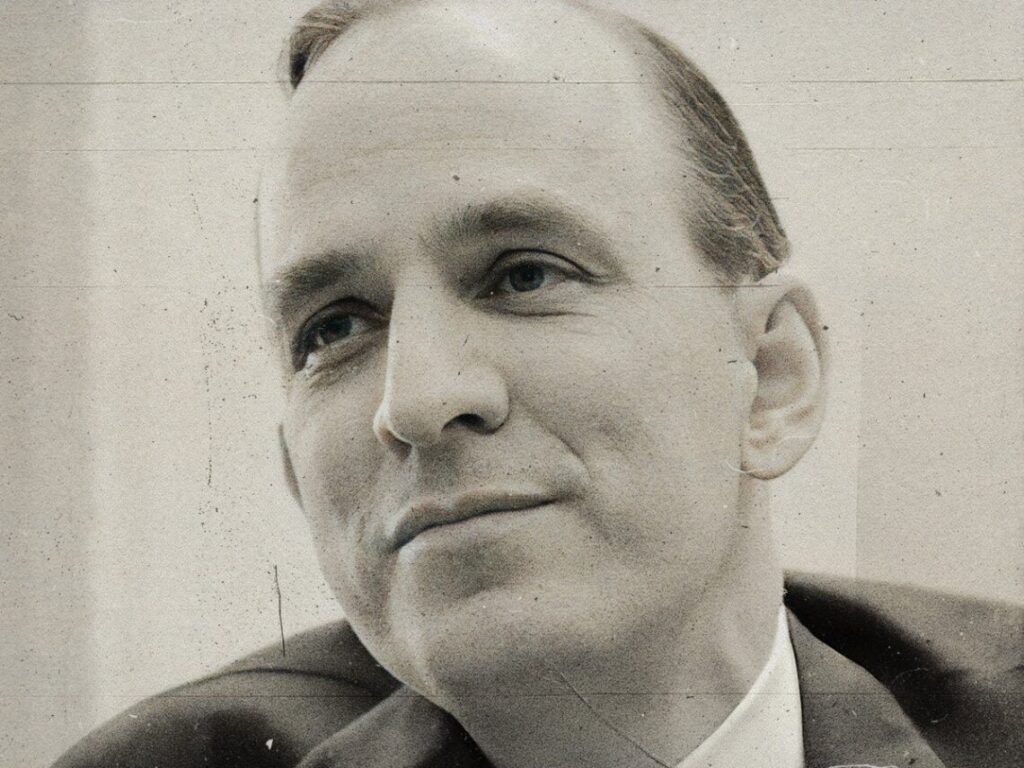

(Credits: Far Out / Joost Evers / Anefo)

Many of cinema’s greatest-ever directors with careers spanning decades are in the position of watching trends, fads, and movements come and go as the sands of the industry continue their never-ending shift, with Ingmar Bergman surprisingly more partial to a landmark moment for America.

The filmmaker’s contemplative, mediative, and achingly personal approach to the art form doesn’t have a great deal in common with the type of films that turned Hollywood into the biggest hub the media has ever known, which makes it surprising that he was a great deal more enthralled with what was happening Stateside in the early 1960s.

As a European auteur who made their features exclusively in Europe, all of which carried a distinctly continental feel in terms of aesthetic and atmosphere, it’s hardly foolish to imagine that Bergman would have placed the French New Wave on a pantheon well above New Hollywood.

At the same time François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Éric Rohmer were rewriting the rulebook of cinematic convention through a number of all-time classics, there was a new generation emerging in Tinseltown who were planning to do the exact same in an entirely different way.

What makes Bergman’s comments even more fascinating is that they came in 1964, which means he believed ‘New Hollywood’ to be superior to its French counterpart in a time before Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Rosemary’s Baby, Easy Rider, or any of the other trailblazers and pioneers had even emerged.

When asked by Playboy if he felt America’s emerging directors had something to say, Bergman answered in the affirmative. “Yes, I do. I have seen just a few examples of their work; only The Connection, Shadows and Pull My Daisy,” he said. “I should like very much to see more. But from what I’ve seen, I like the ‘American New Wave’ much more than the French.”

Shirley Clarke’s experimental found footage film, John Cassavetes’ socially-poignant race relations drama, and the short film co-directed by Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie with improvised narration from Jack Kerouac are three of the earliest ‘New Hollywood’ offerings, and it was more than enough to make Bergman’s mind up.

“They are so much more enthusiastic, idealistic, in a way,” he suggested. “Cruder, technically less perfect and less knowing than the French filmmakers, but I think they have something to say, and that is good. That is important. I like them.”

The French New Wave and New Hollywood represented entirely different ideologies on opposite continents, but as a combined force, they swept through the filmic world and turned it upside down in the 1960s. Bergman didn’t even pass comment on the heaviest-hitting Francophile filmmakers, either, which indicates that he might not have been its biggest fan. The movement was only in its infancy, but he knew something seismic was brewing on the other side of the pond.

[embedded content]