When Salvador Dalí collaborated with Jackie Gleason on his album cover

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Carl Van Vechten / James Koll)

When you think of Salvador Dalí, you immediately think of surrealism, of melting clocks and elephants on stilts. Or you may think of Christ of Saint John of the Cross, The Temptation of St Anthony, and the Metamorphosis of Narcissus. Or you might visualise his famous moustache and his pet ocelots and anteaters.

Meanwhile, when Jackie Gleason is brought up, you may recall his role as Starchy alongside one of the greatest actors of all time, Humphrey Bogart, in the 1942 film All Through the Night. Or, you may think of his later performances in The Hustler, with Paul Newman, and Smokey and the Bandit, starring Burt Reynolds.

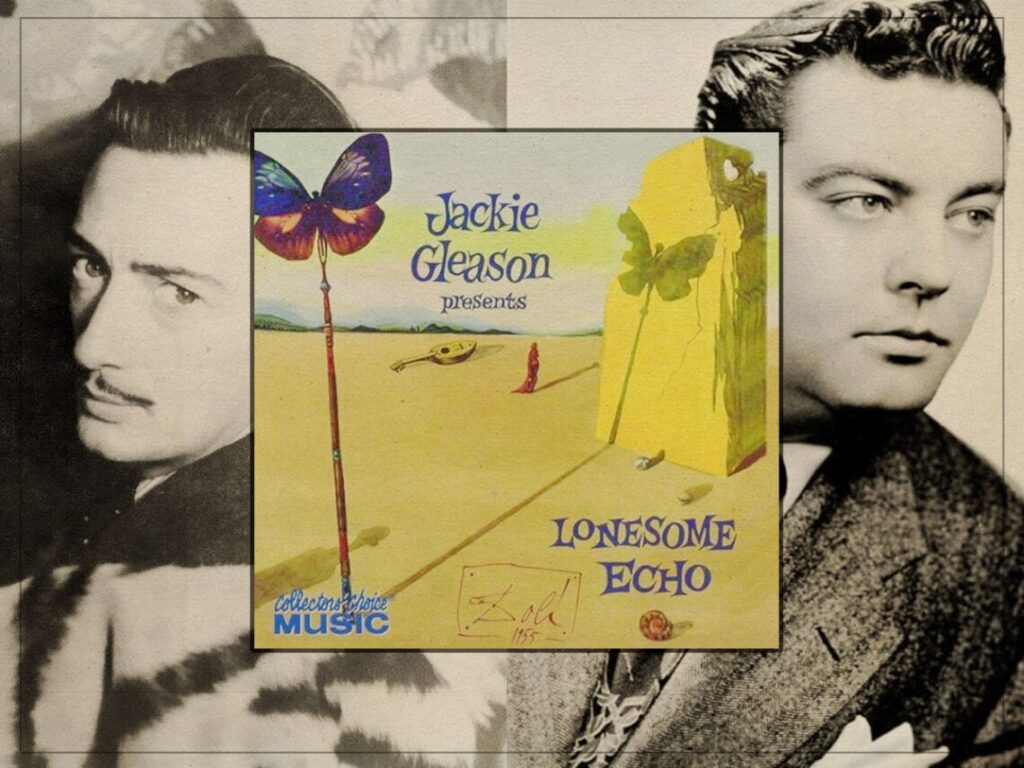

However, if either of them, Gleason or Dalí, come to mind, you are unlikely to find a connection, and you’re even more unlikely to think of lush orchestral mood music or the Great American Songbook. But perhaps you ought to, as the pair were great friends and even came together in 1955 for Gleason’s gorgeous studio album Lonesome Echo.

Released by the legendary Capitol Records, the album went to number one and remained on the charts for half a year. A hazy and enchanting collection, Lonesome Echo is a mellifluous and dreamy presentation of songs like Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer’s ‘Come Rain or Come Shine’, Irving Berlin’s ‘How Deep Is the Ocean?’ and the Rogers and Hart show-tune ‘Dancing on the Ceiling’, as well as some less familiar numbers.

Gleason, who couldn’t read a note of music, conducted an orchestra of strings which included mandolins, cellos, domras as well as guitars and a marimba, all of which lent the record a distinctly Mediterranean feel. The solos, performed by Romeo Penque on oboe, grounded the songs in the more contemporary movie-music style of the time. Owing to the combination of strings and mandolins, cellos and oboe d’amour, the album at times feels like it could be the perfect backing track for something by Dean Martin, while at others like something which would fit right into Disney’s The Jungle Book.

It wasn’t Gleason’s only album, but the collaboration on the cover with Salvador Dalí might make it his most well-known. Dalí’s touch could be found on the back and front of the record. On the reverse, surrounding an image of Dalí and Gleason laughing together and shaking hands, were the liner notes written by the Catalonian surrealist.

On the front was a piece of his art. Featuring the wings of a butterfly perched atop a totem pole in the desert, casting a long shadow on a yellow monolithic rock, while in the distance, a robed monk passes by a mandolin lying in the sand, the album art featured all the hallmarks of a great Dalí piece. Just like all of his best work, the longer you look at it, the more you find, the more it is revealed and unfolds before your eyes, and the harder the meaning becomes to parse.

Dalí made some attempt to explain his work in the liner notes, noting that “The first effect is that of anguish, of space, and of solitude. Secondly, the fragility of the wings of a butterfly, projecting long shadows of late afternoon, reverberates in the landscape like an echo. The feminine element, distant and isolated, forms a perfect triangle with the musical instrument and its other echo, the shell.”

Conversely, the music inside the sleeve doesn’t require nearly as much close attention or thought, and its beauty speaks for itself. Gleason said that this was by design, as his ultimate goal was to create “musical wallpaper that should never be intrusive, but conducive”.

Gleason continued to make music for the rest of his life, and while Dalí didn’t dabble in the medium as much himself, he would continue to work on further album covers throughout his career, all in his trademark surrealist style.

Related Topics