What does the neorealism movement tell us about the reality of post-war Italy?

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Wikimedia / Alfred Eisenstaedt / Alfred Eisenstaedt / NATO)

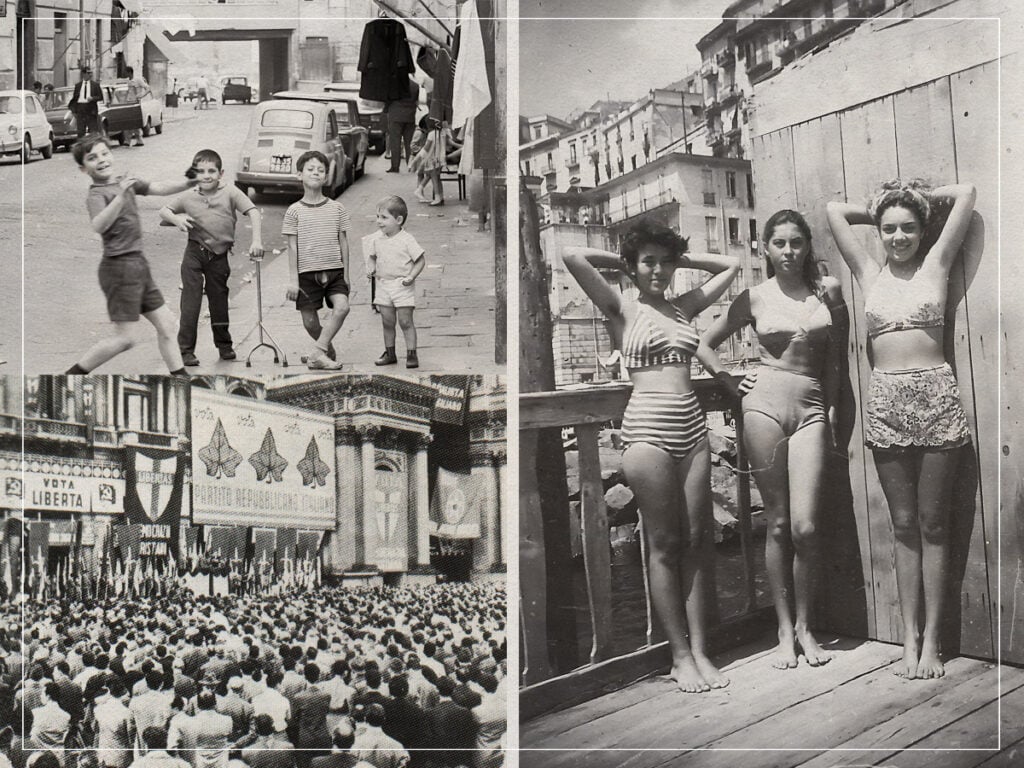

World War II is naturally considered one of the most pivotal events in modern history, with its disastrous consequences rippling through most parts of the globe. Not only were millions of casualties recorded on both sides of the conflict, but the socio-political climates of several countries were also forever altered, with many nations struggling to adapt to life after the war came to an end.

While one most closely associates the fascist regimes of World War II with Nazi Germany, Italy had also been subject to a fascist dictatorship, reigned over by Benito Mussolini, who had served as the Italian duce from 1919 until 1943, when he was executed by Italian partisans. In the years that followed, Italy lay torn apart, with the country’s shared emotional trauma matched only by its ravaged physical and economic state.

As Italy struggled to climb out from its ruins in hopes of newfound political stability and redefinition after the era of fascism that had preceded it, the most prominent filmmakers of the country banded together. They created the neorealism movement, a cultural collective that sought to accurately portray the harsh realities of poverty, economic devastation and the personal wreckage that had become of Italy’s inhabitants.

Prior to the movement’s origins, the Italian film industry had primarily been comprised of overly sentimental, glossy, Hollywood-like studio-led productions that largely overlooked what had indeed become of Italy during the awful global conflict. By contrast, the films of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica and Luchino Visconti started to closely examine the hardships of everyday life in Italy, sticking to an ethos of using non-professional actors and shooting on location to capture an unbridled air of authenticity and honesty.

Italian neorealism, therefore, revealed much about the realities of post-war Italy. At the movement’s core, at least in terms of its narrative position, films under the banner of neorealism focused on the stories of the poverty-stricken, the disenfranchised, the oppressed and the outcast. By telling the tales of the marginalised, neorealist directors informed the world what had become of Italy as a result of Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime and the Second World War.

Take, for instance, Roberto Rossellini’s seminal 1945 neorealism film Rome, Open City. Taking place at the conclusion of World War II during the Nazi occupation of the Italian capital, Rossellini’s film focuses on a group of Italian resistance fighters as they aim to sabotage the plans of the German forces. What Rossellini portrays, though, is the awful circumstance of life in Italy, with a brutally honest depiction of a lack of food supplies, cruelly imposed curfews for Italian citizens and arbitrary-seeming arrests of those who had done little wrong.

(Credits: Far Out / Wikimedia / NATO)

Where Rossellini detailed life in Rome at the end of the Second World War in Rome, Open City, Vittorio De Sica showed the harsh realities of what came next following the conflict’s official end. In 1948, De Sica released his masterpiece Bicycle Thieves, which tells the moving story of Antonio Ricci, a poverty-stricken father searching for his bicycle amid his desperation to find work and support his wife and child.

In the destitute streets of post-war Rome, De Sica details the overcrowded housing situation of the Italian capital during a time of mass unemployment. By using the search for a bicycle as the main narrative avenue, De Sica places the vehicle under the scope of its representation for travel and, therefore, work itself. At the same time, the analogue can also be a symbol of self-reliance, which was sadly rare in the post-war era of Italy’s harrowing history. Antonio’s search for the bicycle has unduly become a symbol of the neorealism movement itself, an enduring icon eternally burned into the cultural retina of European cinema lovers.

Elsewhere, neorealist films explored the cruel economic hardships faced by those seeking a better life in the aftermath of World War II. Luchino Visconti’s 1948 film La Terra Trema documents the struggle faced by a poor group of Sicilian fishermen. As Italian socio-politics shifted into widespread ownership of capital by greedy industrialists, peasant workers were undoubtedly exploited for their labour, and Visconti showed no qualms in detailing the cruel mistreatment of such a cross-section of Italian society, just as De Sica had demonstrated the desperation of retaining a rented property amid widespread eviction with his 1952 work Umberto D.

Still, there is a quiet optimism in Italian neorealism that showed that the movement was not merely aiming to showcase the harsh realities of post-war Italy but to give glimmers of hope that one’s economic prospects and quality of life would one day improve. One of the very first films in the movement, De Sica’s 1946 film Shoeshine, focuses on two optimistic young shoeshine boys who try to gather enough money together to buy a horse – yet another symbolic representation of autonomy and travel – with many Italians seeking a better life away from the harsh confines of their native country.

Social critique had undoubtedly been the flavour of Italian neorealism in general, and most directors showcased the worst conditions of post-war Italian life with little compromise. However, that belief in the human spirit and in the human ability to rise against adversity in moments of personal and social conquest rang true and films with the neorealist ethos at their heart paid dividends in providing Italian society with reason to believe that their fortunes would indeed change – as they invariably did when the Second World War receded further and further into the distance.

Italian neorealism, therefore, provided an invaluable insight into what kind of lives Italian society was experiencing in the aftermath and during World War II. An unflinching documentation of what had become of the European country was undoubtedly challenging to witness. Still, it was a vital time in the history of Italian cinema in that the likes of Rossellini, De Sica and Visconti showed both the truth of Italian society and the resilience of the Italian people as they made strides toward a better socio-political existence.

Chasing the Real: Italian Neorealism is at BFI Southbank from May 1st – June 30th, with selected films also available to watch on BFI Player.

Rome, Open City is re-released by the BFI in selected cinemas from May 17th.

[embedded content]