Three movies that defined Michael Powell as Britain’s most potent filmmaker

Posted On

Posted On

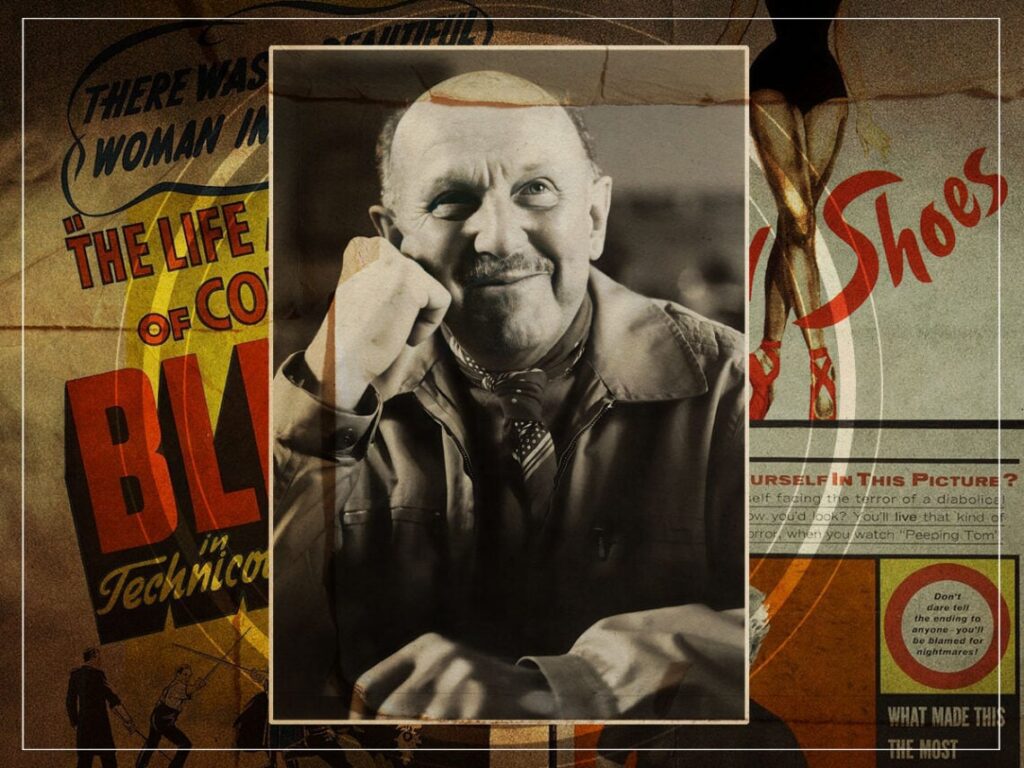

(Credits: Far Out / IMDB / Original Promo)

Although he’ll forever be inextricably linked with Emeric Pressburger for their many seminal contributions to celluloid, Michael Powell was more than capable of thriving whenever he flew solo.

Obviously, it’s completely fair for the duo to be remembered best as a cohesive unit when they were responsible for 24 films made between 1939 and 1972, which saw them forge a unique working relationship that no other duo has been able to replicate, never mind duplicate.

Pressburger was the story-minded of the two, but they’d share screenwriting duties after bouncing ideas back and forth. Powell assumed the lion’s share of directorial duties while Pressburger served in a more producorial capacity during shooting, and he was more heavily involved in post-production than his counterpart.

However, they’d share credit, which was fair enough when they were effectively a hive mind. Their idiosyncratic methodology wouldn’t have amounted to much if they weren’t capable of delivering the goods once their movies hit screens, but a back catalogue of all-time greats makes it patently clear there are innumerable very good reasons why Powell and Pressburger are revered the way they are.

Not to downplay Pressburger’s involvement at any level, but as the more visually driven of the two who assumed command of the directing, Powell was largely the brains behind the sumptuous shot composition, arresting frames, and jaw-dropping vistas that populated many of their best works.

An argument can be made that each of them failed to recapture their unified magic when they went their separate ways, even if there is one notable exception in Powell’s case. Nonetheless, he was one of the most important and potent voices to ever grace British cinema, with the following three films offering the definitive assessment of everything he was as an artist.

Three movies that define Michael Powell:

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943)

Gone with the Wind might be the epitome of Hollywood grandeur, but that didn’t mean Britain wasn’t capable of delivering staggering romantic war epics of its own, with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp combining sweeping storytelling with innovative filmmaking to lay down a new marker for the moving image.

Walking a tonal tightrope by interweaving melodrama, romance, warfare, and satire, the movie ruffled feathers at the very top of the food chain. Winston Churchill blocked its release in the United States after The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp dared suggest that fighting with honour may not always be the best way to emerge on the winning side.

Tracing the life of Roger Livesey’s officer Clive Candy, the narrative is powered by his relationships with Anton Walbrook’s former enemy and newfound friend Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff and Deborah Kerr’s nurse Barbara Wynn, with the trio’s trials and tribulations intersecting at various point in time.

A societal snapshot of British life at the height of World War II in one respect, but on a much grander scale, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp sought to cast its eye over the very essence of what it means to be alive in any location during such fractious times; war, love, friendship, family, society, and politics are all placed under a spotlight, one that doesn’t have any issues placing the decision-makers under its satirical glare.

That universality wasn’t lost on Powell, either, who described it as “a 100% British film, but it’s photographed by a Frenchman, it’s written by a Hungarian, the musical score is by a German Jew, the director was English, the man who did the costumes was a Czech; in other words, it was the kind of film that I’ve always worked on with a mixed crew of every nationality, no frontiers of any kind.”

With all of its Technicolor bombast and accomplished performances, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was a maelstrom of moving parts that managed to achieve more than most films of its ilk. It was a feast for the eyes that entertained and engaged, all while critiquing the socio-political landscape to such an extent that the corridors of power were left enraged.

It goes without saying it’s not the easiest balancing act to pull off, but Powell made it look effortless, with the end result a watershed moment for not just British cinema’s grandiosity, but the resonant thematic undercurrents it can carry even in its most populist guise.

[embedded content]

The Red Shoes (1948)

When Martin Scorsese celebrates a movie that’s affected him so deeply, he can’t imagine his life without it and still manages to find new complexities no matter how many times he revisits the story, it goes without saying that film is a masterpiece.

He’s hardly alone in espousing the merits of The Red Shoes, either, with everyone from Steven Spielberg to Greta Gerwig falling over themselves to sing the praises of a fantasy drama that took everything everybody loved about Powell and Pressburger and ramped it up to new and even more staggering heights.

There isn’t a single frame in the 134-minute running time that isn’t a work of art unto itself, with The Red Shoes the director’s most ambitious feature by far, but executed with such style, grace, and poise that it comes across as being the easiest thing in the world for Powell to put together from behind the camera.

The recurring motif of the titular footwear embodies the passion and sacrifice of Moira Shearer’s Victoria Page, who finds herself wrestling with a choice that’s archetypal in nature. Obviously, there’s nothing formulaic about The Red Shoes, which takes one of the simplest stories to tell and refits it into one of the most beautiful motion pictures ever made.

Victoria is torn between chasing the dream she’d dedicated her life to achieving or following the chance to be loved in the way she’d always desired. There are going to be consequences either way, with magical realism and hallucinatory imagery evoking the mindset of a protagonist who wants two things but remains completely aware they’re never going to get them both.

The production design, choreography, camerawork, and score all work in perfect harmony to concoct a kaleidoscopic exploration of what it means to be alive and what it could cost to live it that navigates its way through drama, romance, dance, and even lashings of horror to yield a timeless tale like no other.

[embedded content]

Peeping Tom (1960)

The initial backlash to Peeping Tom was so vociferous and overwhelming that it ended up doing irreparable damage to Powell’s career, only for the passage of time to gradually place the hybrid of psychological thriller and horror on its deserved pedestal.

The boundary-pushing dive into the seedier side of obsession was reprimanded in Italy for its lurid content and remained banned in Finland until 1981, with British audiences left clutching their pearls at what had become of a director best known for their more classical and palatable works.

While there was more than hint of hyperbole to be found in the reactions, it was cruelly ironic that for the first time in a long time Powell had chosen to use his cinematic voice to test the waters of how far the medium was willing to bend, only to discover that it was so far his reputation ended up in tatters.

It seemed grossly unfair that at around the same time Alfred Hitchcock was being celebrated for Psycho, Powell was fed to the wolves for Peeping Tom when they dealt in many of the same themes and served equal importance in pioneering what would eventually become known as the slasher subgenre.

Carl Boehm’s Mark Lewis is a socially awkward loner who spends his evenings taking voyeuristic photos of scantily-clad women, not to mention his depraved habit of recording the dying reactions of his murder victims for the perverse pleasure of his own snuff film library. Quaint by modern standards, but too shocking for most back then.

A treasure trove for Freudian scholars everywhere, Peeping Tom gained headlines for its graphic nature, but the way Powell incorporates complex reflections on mental fragility, the depths of desire, and the inherent – and innovative – subversion of treating the audience as voyeurs in a movie about voyeurism were swept under the rug in favour of the outrage.

[embedded content]

Related Topics