The touching, emotional sparseness of Kelly Reichardt’s ‘Old Joy’

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Criterion Collection)

Known and loved for her minimalist contributions to the slow cinema genre, which is broadly defined by its free narratives and long takes, Kelly Reichardt is considered a vital name in the independent American film industry. Among her greatest works are the likes of River of Grass, Wendy and Lucy, Meek’s Cutoff, Certain Women, First Cow and Showing Up.

Reichardt’s films often detail the lives of working-class people in small, rural American towns, and in 2006, she kicked off a series of dramas set and filmed in Oregon with Old Joy, a stunning piece of cinema that explores the naturally changing course of friendship as we grow individually and transition into new periods of our lives.

Adapted from a short story by Jonathan Raymond, Old Joy focuses on two old friends, Mark and Kurt, played by Daniel London and Will Oldham, respectively, who come together for a weekend camping trip in the forests of Oregon. As is often the case with a Reichardt movie, the film eschews an intense narrative in favour of capturing the subtleties and minute emotional resonances of its characters.

Away from high-stakes drama (how awful this film would be if Mark and Kurt encountered a vicious bear), Old Joy trundles along at a contemplative pace, entirely in line with its stunning natural setting and patient Yo La Tengo score. Mark and Kurt’s journey to nowhere is truncated by snippets of conversation, mostly about nothing, only occasionally tapping into their evidently dying (if not dead) friendship.

Kurt is still living a hippie hand-to-mouth lifestyle, while Mark has seemingly moved on; he has a proper job, his wife is pregnant and he spends his driving time listening to debate public radio. Naturally then, Kurt and Mark have drifted in the years preceding Old Joy, but they seem to be clinging to what once was, the “glory years”, so to speak.

The old friends’ relationship is essentially where Reichardt does most of her emotional damage, but it’s in the words not said between Mark and Kurt through which we feel the most uncomfortable. At one point, Kurt almost breaks through and tells Mark that he wishes there was a way to get rid of whatever is going on between them, but Mark understands that he’s largely finished with his constantly stoned friend and that he’s suddenly “grown up” himself.

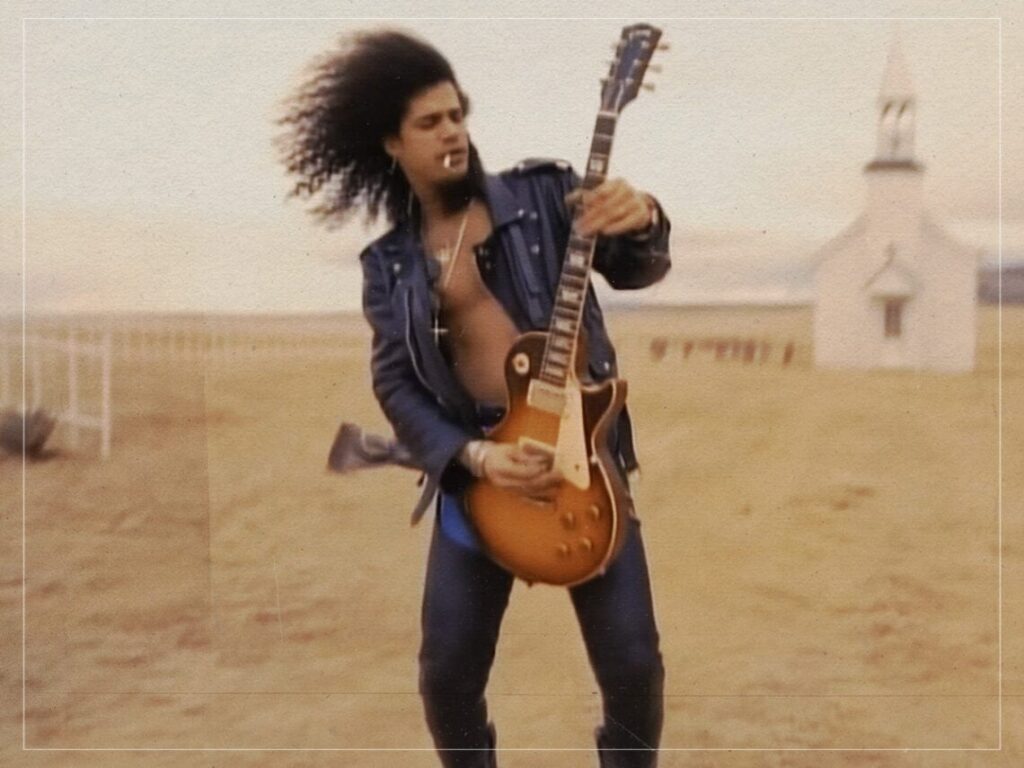

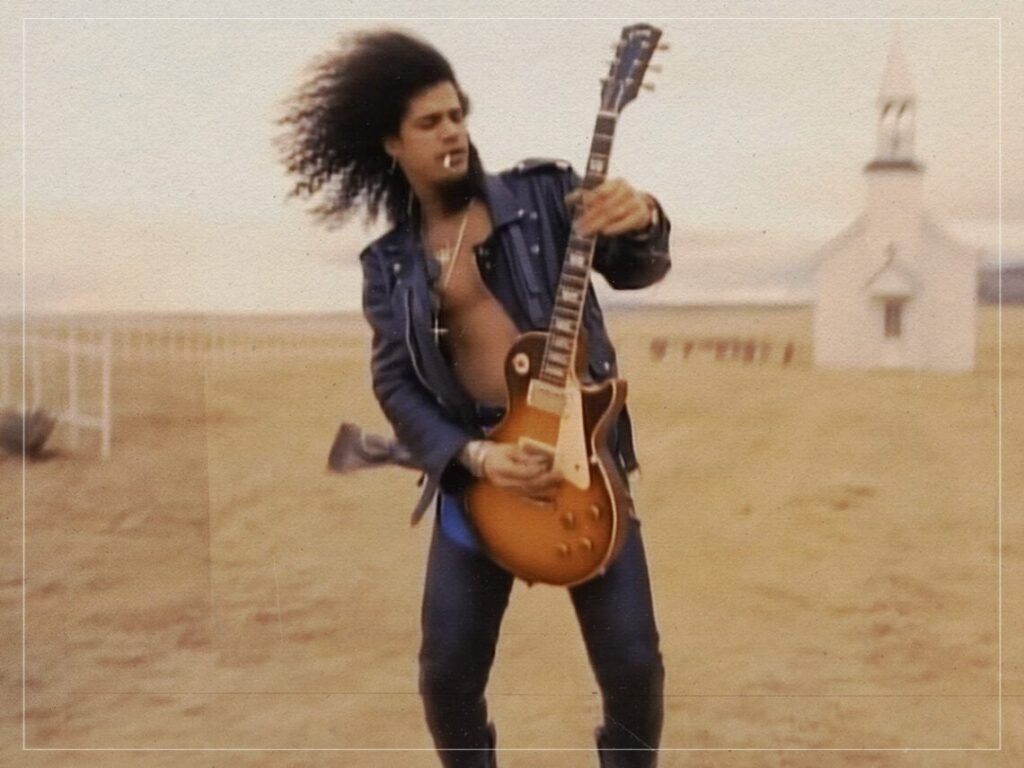

This kind of narrative exposition is elevated into new artistic heights by the aesthetic and production choices of Reichardt, though, whether through the finger-picked guitar work of Yo La Tengo or the constant hum of the cicadas, which makes the occasional silence between Mark and Kurt all the more deafening, thereby making their disillusionment from one another heartbreakingly more evident.

With stunning wide-angle shots of the Oregon wilderness and naturalistic long takes, Old Joy is a film that arrives in a simultaneously tranquil yet problematic manner. A walk through the forest ought to be a welcome escape from the pressures of life, especially with an old friend, but there’s something ugly that bubbles beneath Mark and Kurt’s journey, a hidden devastation that arrives as a result of Reichardt’s sparse approach.

Male friendship is often defined by its loud, beer-guzzling masculinity, but something different is afoot with Mark and Kurt, a suspected loneliness that neither can confront even with the help of the other. Old Joy is a stunning film that works its magic on you slowly, and it serves as a beautiful examination of the passage of time and the emotional consequences of the lack of human connection.

[embedded content]

Related Topics