The surprising role of karaoke and live music in the work of Aki Kaurismäki

Posted On

Posted On

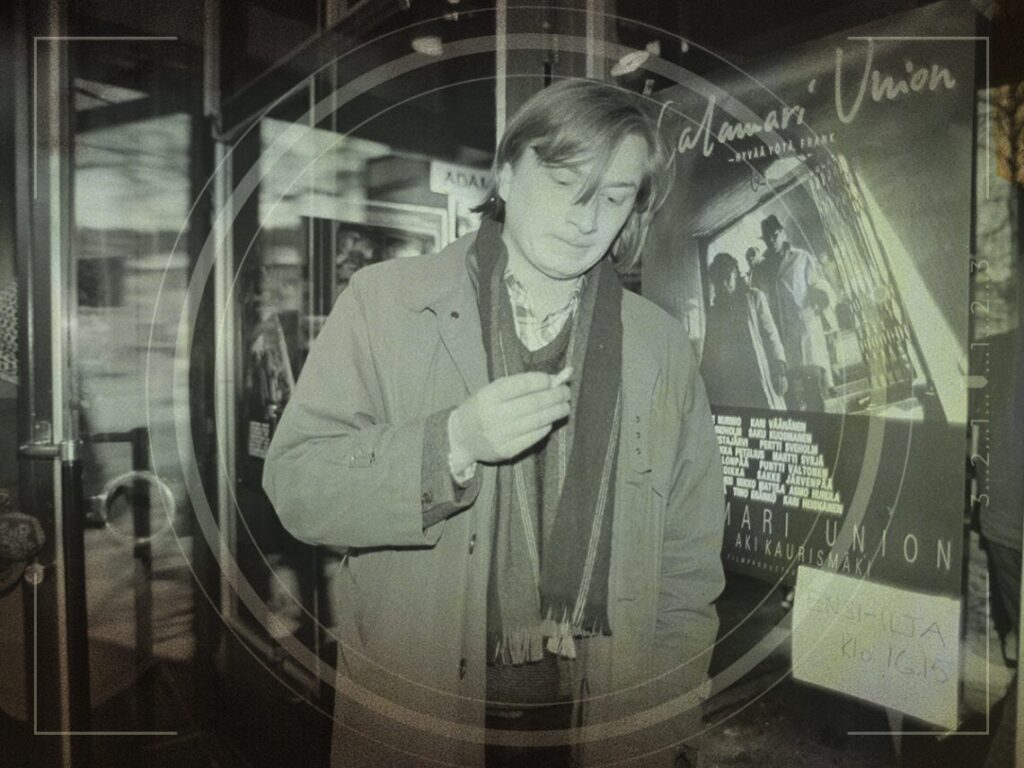

(Credits: Far Out / Finnish Heritage Agency)

The Finns are not known for their optimism, yet despite this, Aki Kaurismäki’s films have become the ultimate cure for all the tortured souls and cynics of the world. There’s a lightness to his work that creeps up on you in spite of the often-heavy subject matter, with the director infusing his timeless critique of Capitalism into stories about characters who find beauty and community within the darkness, resisting in their own quietly beautiful ways. From Le Havre to The Match Factory Girl, Kaurismäki’s films offer a delicate and muted reality, washing over you in their simplicity and inducing a sense of melancholic calm in spite of their bleakness. The characters miraculously survive the horrors of an uncaring world through their touching efforts to create community and connection, finding ways to reinsert humanity into a broken system and find a gentle power in their compassion for others, no matter how little they have.

Often centering around working-class people, Kaurismäki is the unsung hero of untold everyday stories, with each film being touched by misery and the struggle to survive while simultaneously being grounded in hope, with the pursuit of love naturally breeding optimism and a yearning for something better, no matter how unattainable this may seem. Kaurismäki often expresses this tonal clash between hope and pain through one narrative device in particular, something that is most prevalent in his 2023 film, Fallen Leaves.

Set in modern Helsinki, Fallen Leaves follows two lonely people who cross paths in a karaoke bar one evening, encountering constant obstacles on their journey to find love, whether it be lost phone numbers, stray dogs or alcoholism. What is most striking about Fallen Leaves is the bleakness of their world and the sobering realisation that this film takes place now, with the characters leading lives that feel reminiscent of a lost era. The city feels harsh and devoid of beauty, with Ansa and Holappa working thankless jobs that pay them just enough to survive, with few material possessions that would signify a modern life. However, there is a scene in which we see a calendar on the wall that reveals it is set in 2023, shocking us in the cold reality of late-stage capitalism and those who work long and unrewarding jobs with little to show for their efforts.

After meeting at a karaoke bar one evening, with the couple barely uttering more than a few sentences to each other, we realise that love and human connection is the key to surviving this life and making it bearable. We have seen their lives without the presence of love, and it is difficult, but this darkness is lifted with the possibility of romance and a person to share it with, making this fleeting connection all the more precious.

However, Kaurismäki reiterates the value of their blossoming love by making it nearly impossible to reach, with the couple encountering a comical number of setbacks in their efforts to kindle their relationship, with Holappa losing the sacred piece of paper with her phone number, the key to reconnection, then eventually meeting and driving her away as a result of his alcoholism and breaking his leg.

There comes a point towards the end where we wonder if these crazy kids will ever work it out, with Kaurismäki fluctuating between hope and misery as they reach for each other only to be torn away. It forces us to reckon with just how dehumanising their lives are without the promise of love, with nothing outside of their work to assert their humanity, existing as cogs within the capitalist machine. This emotional clash is highlighted through the karaoke scene towards the end of the film, with Holappa drinking alone in his misery over not being with Ansa, which is accompanied by a trio of Finnish girls who sing whose title translates to Born in sorrow and clothed in disappointment.

Interestingly enough, this isn’t the first time that Kaurismäki hasn’t used a live karaoke performance in one of his films, with the director also using this narrative device in Le Havre. After noticing it again in Fallen Leaves, I began to think about the meaning behind this choice, and drew correlations between the tone, lyrics and placement of both songs.

Born in sorrow and clothed in disappointment has incredibly bleak lyrics, despite the slightly comical way in which the trio are dressed. It’s a touching and poignant moment in the film, with Holappa reckoning with everything he has lost and the reality of a life without love. The anti-capitalist sentiment is reflected in the lyrics, with the song describing someone who is a prisoner in life and looking forward to the freedom only offered by death. Each chorus repeats the line, “I am a prisoner here forever, fences also surround the cemetery, when the earthly wash would finally end, but they only dip deeper into the ground, I like you but I can’t stand myself”.

It’s a truly devastating moment and one of the few in which Kaurismäki allows himself to fully linger in the misery of the story, creating a balance between hope and pain for the rest of the film besides this one moment. He only allows himself to explicitly wallow in sadness when paired with a musical sequence, perhaps as a way of immersing the audience in this mood and hammering in the true tragedy of this story, confronting us with the reality of Holappa’s life through the lyrics. While many audiences won’t understand what the trio are saying, the tone of the scene somehow implies the thematic weight of the lyrics, communicating a profound sadness even to those who don’t understand a word of Finnish.

While Kaurismäki’s films communicate a miraculous sense of hope and optimism despite their subject matter, he reiterates the urgency of his anti-capitalist critique and the brutal consequences of this system through the use of live music, allowing for one moment in which he abandons the uplifting overtone and dwells on the true gravity of his message. By conveying this through music, it could either be Kaurismäki’s way of shielding us from this darkness or exaggerating it, but either way, we feel unsettled by its raw vulnerability and unblinking hopelessness, reminding us of the true evil at the heart of his films and briefly reconnecting us with a deeply familiar Finnish sentiment.

[embedded content]