The stone-cold thrills of ‘The Hitch-Hiker’, the first film noir directed by a woman

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / TCM)

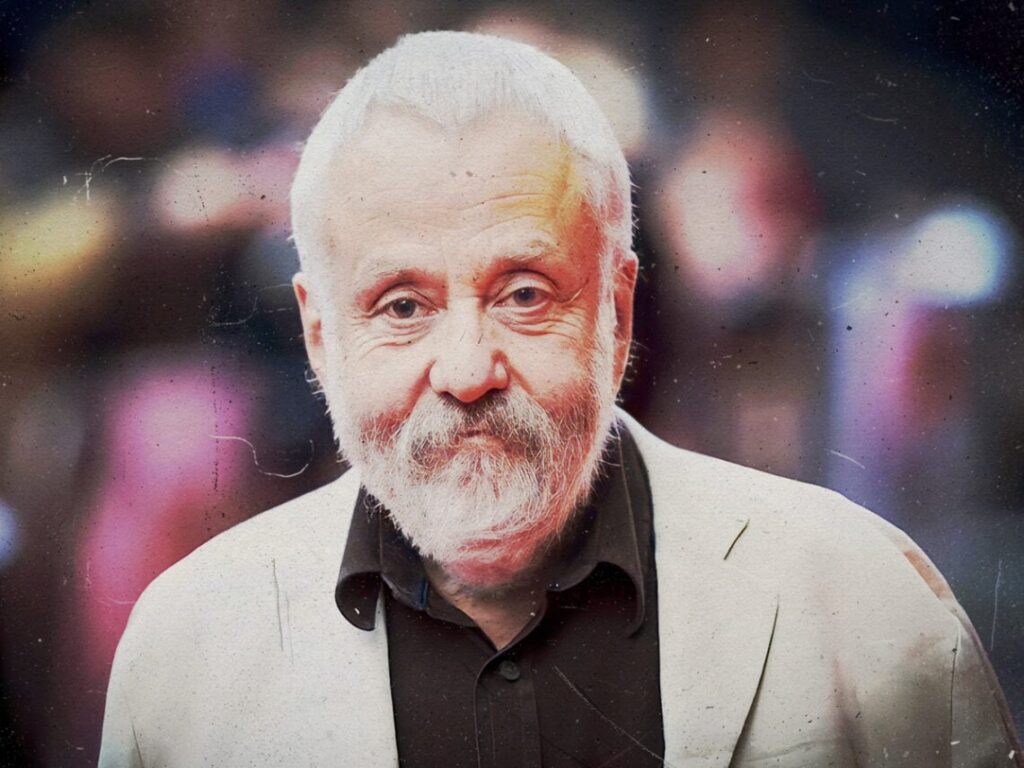

In 1950, there were only two women in the Directors Guild of America: the pioneering filmmaker Dorothy Arzner, whose career began in silent pictures but whose final movie was released in 1943, and Ida Lupino, a former Hollywood starlet who had just started her career as a director and was already wreaking havoc with her decidedly unglamorous take on filmmaking. Although Lupino never became a mainstream auteur on the scale of Billy Wilder or John Huston, she directed some of the most daring and socially relevant films of the era in the guise of low-brow B-movies. The plot of her 1953 film The Hitch-Hiker was pulled straight from the headlines, and it made her the first woman to ever direct a film noir picture.

Lupino was born into a showbiz family in London in 1918 and began to act in movies as a teenager. At just 15, she was discovered by Paramount and earned a contract that took her to Hollywood. She played young vixens in the mould of Jean Harlow during her early career before transitioning to hard-edged roles in the 1940s, playing women attached to dangerous men. High Sierra, her most famous film, saw her playing the girlfriend of a gangster who falls for a hardened criminal, played by Humphrey Bogart.

In the late ‘40s, Lupino started a production company with her then-husband Collier Young called The Filmakers. She would later say that her interest in directing arose during her lengthy periods of downtime on movie sets while working as an actor. But she didn’t want to make just any type of movie. The mission statement of The Filmakers was to write, produce, and direct low-budget, issue-oriented films, and they followed through.

The first film Lupino directed, Not Wanted, was about pregnancy out of wedlock, a taboo subject at the time. Although Elmer Clifton is credited with directing it, Lupino did the bulk of the work after he suffered a heart attack. It became a surprise hit despite the subject matter and allowed her to continue making movies. Her next film, and the first one with which she is given sole credit as director, was the 1950 drama Never Fear, which drew on her personal experience of contracting polio. She followed it up with Outrage, which is centred around the rape of a young woman. Although the attack is only alluded to, there is a lengthy sequence that shows the rapist stalking his victim through the street. She would later make films about a female tennis prodigy and, of all things, bigamy.

In the context of Lupino’s other movies, The Hitch-Hiker was perhaps her most mainstream, at least in its plot. Based on the real-life crimes of William Edward Cook Jr, it follows two men who are taken hostage at gunpoint by a hitchhiker in the rural desert of Mexico by an escaped convict and forced to drive him to a remote town where he can catch a ferry to freedom.

Film noir was one of the most popular genres to emerge during World War II. Featuring cynical heroes, expressive use of light and shadow, and a pervading sense of futility, they were in concert with the general mood of the cinema-going audience. Hollywood glamour gave these films a visual style all to themselves, especially when it came to the trope of the femme fatale, a female character who lures the protagonist to his doom, either knowingly or accidentally.

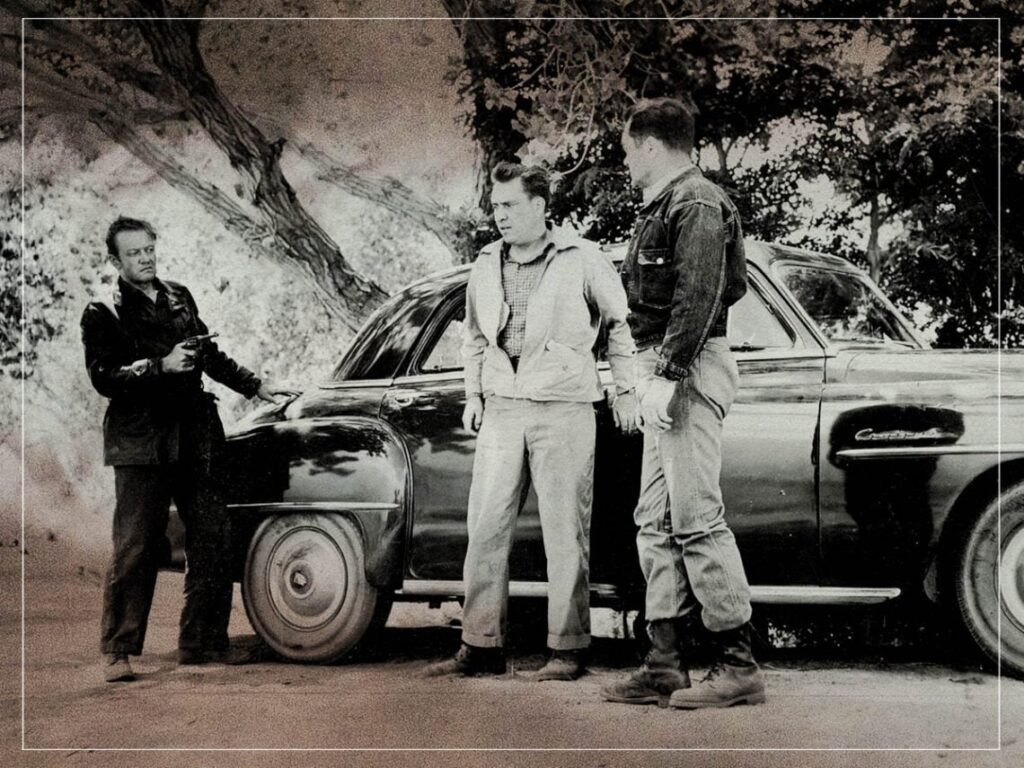

Starring Edmond O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy as motorists Roy and Gilbert and a grizzled William Talman as the titular villain Emmett Myers, The Hitch-Hiker is notable for eschewing female characters in favour of exploring male relationships. As Myers slowly wears away at their resolve, Roy and Gil rely on each other for comfort. Without a female character to play the damsel in distress or the femme fatale, it is the men who are vulnerable and Myers who toys with their increasingly frail emotional states.

The film is also notable for its use of outdoor settings. Instead of being shot on a carefully lit soundstage, it takes place largely in the open desert. Where shadows are often used as metaphors for the human psyche in film noir, The Hitch-Hiker uses the barren, wide-open vistas of Mexico as a metaphor for isolation and loneliness.

Lupino also manages to create a sense of mounting terror with very little action. A series of small reveals – the doubt as to whether or not Myers’ gun has bullets, the revelation that Roy and Gil have their own shotgun, the fact that Myers has a “bum eye” that means he literally sleeps with one eye open – keep the tension high. At the same time, Lupino shreds the nerves of the audience by introducing a grating series of underlying stress. A car horn won’t turn off. A dog barks continuously. A child asks a few too many questions.

At the end of the film, Lupino sidesteps convention yet again. While the Hays Code dictated that villains could not go unpunished, she found a way to pull the rug out from under any hope of redemption. Only when Myers is handcuffed by police do Roy and Gil find the nerve to attack him. And once he’s been hauled away, their staggering gaits and haggard faces are anything but triumphant. As they walk into a darkened shipyard in an unknown town, their futures seem anything but bright.

The Hitch-Hiker was not a success when it was released, though one critic did praise Lupino’s “masculine strength” as a director. Instead, it has become another masterpiece that has only received its due after the death of its creator. Lupino went on to direct several more movies, but lack of funding after her divorce from her producing partner meant that she eventually moved into television. She worked as a jobbing director on series like The Twilight Zone and Bewitched before her death in 1995. Three years later, The Hitch-Hiker was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant,” and is now considered a classic of the film noir genre.

[embedded content]

Related Topics