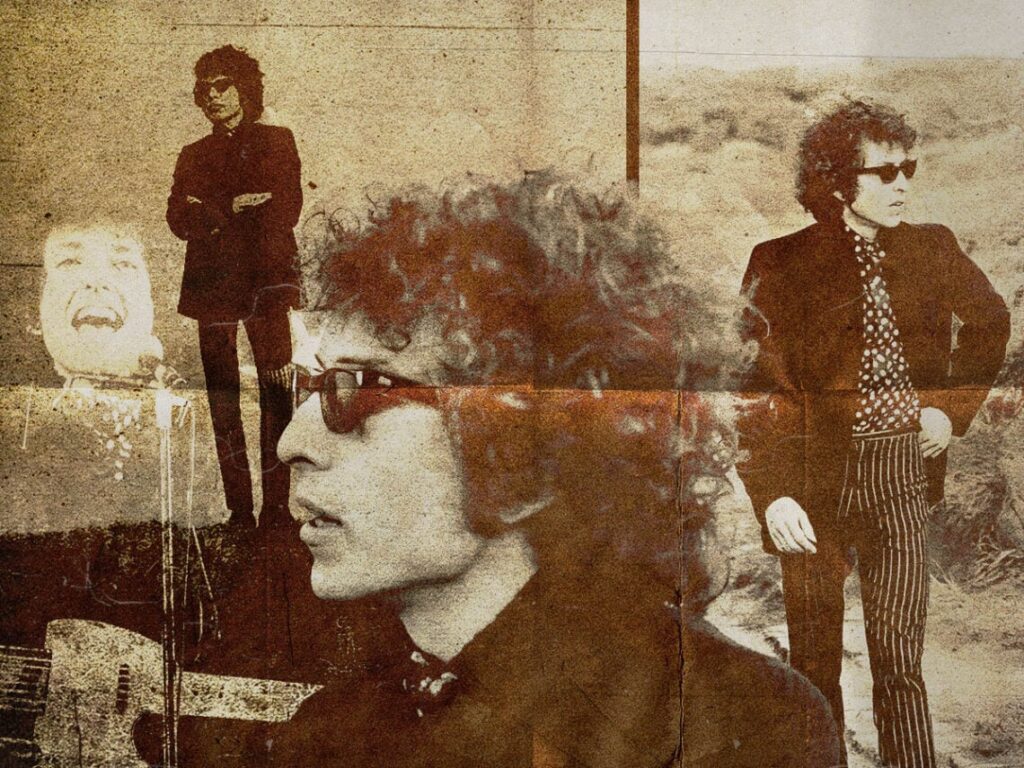

The muses behind Bob Dylan’s ‘Blonde on Blonde’

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Bent Rej)

Bob Dylan is famously tight-lipped and tricky. As an artist, he is one of the most globally respected names in history. He’s held up as a kind of God-like genius, turning the folk of the 1960s into something newer and bigger. For millions, he’s the epitome of a musician, the person all paths seem to lead to. However, when it comes to the person of Robert Zimmerman, he’s impossible to pin down, and his inspirations are even more so.

The figure of Bob Dylan really exists in a web of purposefully spun lies. When he first broke into the big time, he spread a whole false origin story about himself. “I was with the carnival off and on for six years,” he claimed, pretending like he spent his youth as a clownish runaway. He didn’t. But that early example shows exactly the type of celebrity Dylan is, one that will always throw people off his tracks.

So naturally, when it comes to the real-life inspiration behind his songs, he was never going to come right out and say it. Even to the people in his life at the time when he wrote some of his biggest tracks, his personal life was held like a high-stakes secret. He’d turn up one day and suddenly be married, religious or playing an electric guitar, never letting anyone in on the thought processes or inner moving beforehand.

But if you look for the clues, they’re there. Amidst the poetry of his lyrics, Dylan’s muses regularly peak through the codified clues and images. On his 1966 album, Blonde On Blonde, he couldn’t hide the various breakups, breakdowns and breakthroughs going on. Perhaps more so than any of his other albums, this one is clearly and richly about his life and the people that were in it, whether he denied ever knowing them or not.

Painting a portrait of his mid-1960s life, especially his New York years spent spiralling around the world of the Chelsea Hotel, Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgewick, various characters play a vital role. Singers, lovers, artists and beyond are the classic album’s muses.

The muses behind Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde

Edie Sedgwick

“Everyone knew she was the real heroine of Blonde On Blonde,” Patti Smith wrote in a eulogy poem to Andy Warhol’s superstar, Edie Sedgwick. And she was right. Sedgwick, more so than anyone else, colours this album. In almost every track, there is some clue that draws back to the model, yet Dylan still claims he barely knew her.

But he almost certainly did. The pair met in the mid-1960s as both lived at the Chelsea Hotel and seemed to share a mutual fascination with each other. “She called me up and said she’d met this folk singer in the Chelsea, and she thinks she’s falling in love,” Sedgwick’s brother Jonathan remembered, “She sounded so joyful instead of sad. It was later on she told me she’d fallen in love with Bob Dylan.”

But then it went sour. Dylan hated Andy Warhol and his control over Sedwick. He couldn’t seem to get on with her lifestyle, and then, in 1966, he delivered the final blow to the lovelorn starlet when he married Sara Lownds behind her back. “Her biggest joy was with Bob Dylan, and her saddest time was with Bob Dylan,” her brother wrote.

That is reflected across the record, which becomes a jagged and regularly cruel piece. ‘Just Like A Woman’ is the most vivid and sweet sign of Sedgwick as Dylan paints a picture of the damaged figure: “With her fog, her amphetamine, and her pearls.” But as he sings, “Ain’t it clear that I just can’t fit, Yes, I believe that it’s time for us to quit,” he’s already signalling the end.

The rest of the songs on the record aren’t quite so nice towards her. ‘Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat’ takes callous jabs at Sedgwick’s mental hospital stints, mocking her. ‘One Of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later)’ is an absolute masterclass in the worst apology possible. Throughout the album, Dylan’s various references to wealth and broken down women all take the form of a blow thrown at Sedgwick as he sings of being “helpless like a rich man’s child”.

[embedded content]

Andy Warhol

Naturally, as Edie Sedgwick is the muse of Blonde On Blonde, Andy Warhol is there too. Through their toxic friendship, Warhol really held the keys to his starlet. Dylan saw that dynamic clearly, writing it into ‘Temporary Like Achilles’ as he sings, “Achilles in your hallway / He don’t want me here, he brags.” Deeming the pop artist as Achilles, the play on the idea of an Achilles heel presents Warhol as Sedgwick’s weakness and the thing that will lead to her downfall.

Just as he routinely signals towards the ‘Poor Little Rich Girl’ star, he equally throws swords at Warhol and his drug-fuelled world. In ‘Just Like A Women’, he paints the artist and his world out to be Sedgwick’s “long-time curse”.

“After he stole my baby / He wanted to steal me,” he sings in ‘Pledging My Time’ as a possible reference to the infamous screen test he did for Warhol as biographers wrote, “he [Warhol] was clearly star-struck, in awe of Dylan’s sudden, vast celebrity. He had a more practical agenda, too: to get Dylan to appear in a Warhol movie.” After that screentest, he made his thoughts on Warhol vividly clear when he traded an original Elvis print for a sofa.

[embedded content]

John Lennon

Another star Dylan was taking jabs at on Blonde On Blonde was John Lennon. Despite the Beatles declaring the folk singer their “idol”, the feeling wasn’t mutual. It started out so nicely when the musicians met in 1964, when Dylan introduced the Liverpool boys to weed. But when ‘Norwegian Wood’ came out in 1965 on Rubber Soul, it went sour.

“What is this? It’s me, Bob. [John’s] doing me! Even Sonny & Cher are doing me, but, fucking hell, I invented it,” Dylan said about the track. In response, he mocked the track on ‘Forth Time Around’, parodying the tight rhyme scheme, guitar picking and jovial melody. He finishes it off with a final message to Lennon, “I never took much, I never asked for your crutch Now don’t ask for mine.”

[embedded content]

Joan Baez

If Edie Sedwick was stung by Dylan’s sudden and secret wedding, Joan Baez was wounded. When Dylan randomly married his girlfriend Sara Lownds after never expressing any interest in the institution, his tour manager famously asked him, “‘Why Sara?! Why not Joan Baez?’”

To which the musician delivered one of the most eye-roll-inducing responses in history; “Because Sara will be home when I want her to be home, she’ll be there when I want her to be there, she’ll do it when I want her to do it. Joan won’t be there when I want her. She won’t do it when I want to do it.” Dylan’s dismissal of Baez’ talent and desire to not be overshadowed is well documented in her track ‘Diamonds and Rust’. “My poetry was lousy, you said,” she sings in a devastating recounting of their love.

But the clue to Blonde On Blonde lies in his most cryptic and winding track, ‘Visions Of Johanna’. Despite being written while living with his future wife, Dylan seemed to be pining for Baez. “And Madonna, she still has not showed,” he sings, seemingly referencing the way his old love was nicknamed the “barefoot Madonna”. Baez seems to confirm the connection on her track, singing, “The Madonna was yours for free”. It could be that throughout the entire track, the “visions of Johanna that conquer my mind” were memories of his old flame.

[embedded content]

Sara Lownds

Really, considering he married her, more songs should reference his future wife, Sara Lownds. But even the one that does feel uncertain. On his later track, ‘Sara’, Dylan remembers “staying up for days at the Chelsea Hotel / writing ‘Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands’ for you”. In a rare and clear confirmation of his muse, he announces that the song is about her. Even the title, especially “Lowlands”, feels like a direct reference to Lownds’ surname.

However, there have been some disputes. It was during his time at the Chelsea Hotel that Dylan and Sedgwick were together, with some claiming “sad-eyed” would be a perfectly fitting description for the star. Joan Baez, at one point, even thought the track was about her. But really, we have to take Dylan’s word for it here that this song is, in fact, about his wife.

[embedded content]