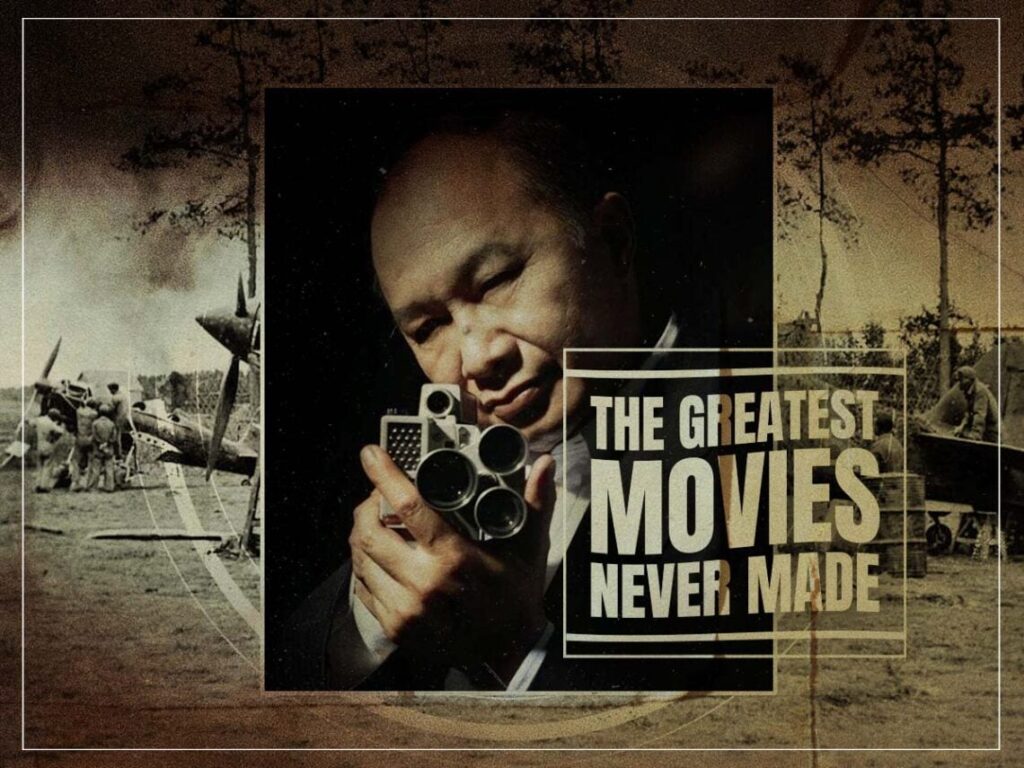

The greatest movies never made: John Woo’s ‘Flying Tigers’

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / MUBI / Picryl)

Having reinvented the face of action cinema through his landmark contributions to the genre in the late 1980s and early 1990s, John Woo was well within his rights to believe he could make the same type of transformative impression in Hollywood.

Unfortunately, his decade-long detour to America was a disappointment in the grand scheme of things, with only Face/Off holding a candle to his multitude of prior masterpieces, including A Better Tomorrow and its sequel, The Killer and Hard Boiled.

However, returning to his native China was exactly the recharge his batteries needed, with Woo mounting the ambitious two-part historical epic Red Cliff, which was one of the very few period-set blockbusters to justify the craze that exploded in the wake of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator.

The prospect of Woo not only returning to the past but actively seeking to channel the spirit of both Saving Private Ryan and Band of Brothers in one fell swoop was as monumentally ambitious as it was mouth-watering, which makes it all the more disappointing that Flying Tigers never managed to make it to the starting line.

Of course, one obvious cause for concern was that Woo had already made a big-budget war movie, and Windtalkers wasn’t very good. As expected, the action sequences were a thing of beauty, but everything else was sorely lacking. It was a box office disaster, a critical pariah, and not exactly the film to intimate to the wider world that Woo and warfare went hand-in-hand.

Flying Tigers was a story much closer to his heart, though, one that would have allowed him to indulge the Hollywood side of the business to a certain extent but also gave him the opportunity to work on native soil, which is where all of his greatest-ever features were made. Throw in an enticing release strategy, and it had every chance of being yet another masterpiece from an action icon.

The titular outfit was the nickname given to the First American Volunteer Group, an organisation formed and populated by American pilots to assist the Chinese Air Force in repelling the Japanese invasion during World War II. Recruited before Pearl Harbor and deployed overseas, their goal was to take the fight to Japan and protect China while training local aviators on how to take to the skies and defend their homeland using techniques and tactics developed and deployed by the United States military.

Intended to be an English-language production featuring an ensemble cast of Chinese and American stars, there was talk at various points of Liam Neeson and Woo’s Mission: Impossible II compatriot Tom Cruise getting involved to add a heavy dose of international star power, but Flying Tigers didn’t even get as far as starting the casting process.

Aware that he was trying to capture two markedly different audiences for the same project, an ingenious strategy was devised to ensure that most people saw it. In China, Flying Tigers would be released as a two-part epic, something that had worked incredibly well for the filmmaker’s Red Cliff when it earned more money at the local box office than James Cameron’s Avatar.

In the United States, the two movies would be re-edited into a six-hour miniseries that would air on television, which is how it earned comparisons to both of Steven Spielberg and Tom Hank’s World War II classics. In an interview with Deadline, Woo hinted that the expense was the number one obstacle that thwarted his passion project.

Calling it “a very big Hollywood-style, big budget action movie,” the auteur confessed “it was hard to get financed” when there were so many practical and CGI requirements, noting that “it would have had a budget equal to Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor,” which came in at a cost of $140 million.

An action-packed war drama helmed by a director who’d recently returned to the top of their game with Red Cliff that could be experienced either as two movies or a single TV series detailing one of the most unheralded and interesting substories of World War II sounds incredible, but not even a talent as well-versed in studio politics as Woo could convince the financial power players the American and Chinese co-production was a financial risk worth taking.

[embedded content]

Related Topics