The Ballad of Booze: Carson McCullers’ favourite cocktail

Posted On

Posted On

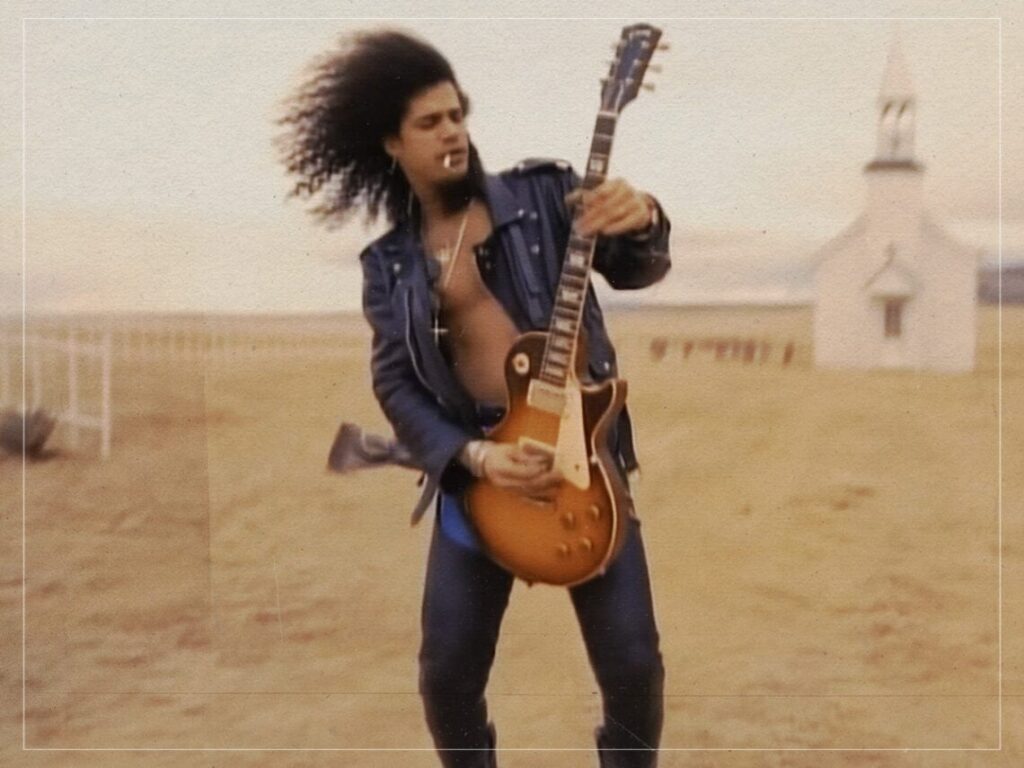

(Credits: Far Out / YouTube Still)

The arts seem eternally bound to alcohol and psychoactive drugs. Some of these substances supposedly enhance creativity, as Aldous Huxley suggested in his 1954 essay The Doors of Perception, and others seem to leave the creative mind in a state of perplexion and inertia. Even William Shakespeare, who was not known to be an alcoholic on the level of his contemporary Christopher Marlowe, rarely wrote a play that didn’t reference alcohol.

Thanks to high-functioning mescal and tequila addicts like Malcolm Lowry, the heady Jazz Age soirees of F. Scott Fitzgerald and the wild hedonism of Hunter S. Thompson, we tend to associate 20th-century literary figures with the ailment of alcoholism. Still, the craft is long-steeped in the lincture. In his verse epic Don Juan, Lord Byron shed some light on the matter, “Man, being reasonable, must get drunk; / The best of life is but intoxication.”

Many a writer has banged their head against the bottle in fits of consumption, often allowing the bottle to consume them. However, somewhere between the blurry parties, drunken walks home, and the sore head in the morning lie the foundations for affecting, imaginative writing. Ernest Hemingway may have lived longer had he never discovered France’s deceptive grape juice, but arguably, his literary career depended on the mood swings and creative stupors it induced.

Although many of our famous writers like to alter their mental states using drugs and alcohol, their approaches vary wildly. In Hunter S. Thompson’s case, it involved a daily routine of rising at 3pm, carving out a line of cocaine with a late lunch, chasing with more cocaine, Heineken, grass and Chivas before dropping acid at 10pm, ready to start writing at midnight.

Naturally, most writers wouldn’t be able to survive Thompson’s routine, let alone write in it. For many, drinking would be the evening-time reward for a day of writing against the oppressive yet curiously helpful tide of a hangover. This was certainly the case for Fitzgerald, who refrained from drinking while working at his typewriter. Meanwhile, his contemporary novelist, Carson McCullers, liked a hair of the dog session to get the best of both worlds.

McCullers, the novelist, playwright, essayist, and poet famed for The Heart is a Lonely Hunter and her play The Square Root of Wonderful, among other seminal works, allegedly left some of her contemporaries in the dust when it came to booze—not that it’s a competition. Tragically, as much as some of our beloved writers enjoyed a drink, it all too often became a factor in their premature demise.

According to Carson’s first biographer, Virginia Spencer, she was fond of sherry tea and whiskey, often in quick succession of one another. “She sat hunched over her typewriter wearing a sweater and leather jacket, drinking scalding sherry tea and an occasional double shot of whiskey,” Spencer documented. She noted elsewhere that McCullers would often write with Tennessee Williams, him at one end of the table and her on the other with a giant bottle of whiskey between them.

Famed composer David Diamond, who entered into a complex romantic relationship with McCullers, revealed her favourite cocktail to unwind with after a day of writing. “Carson was seated in the living room, of course sipping, as tho’ it were sugar water, a whiskey highball,” he wrote in a memoir. She would then straighten out the following morning with a few soft beers.

Carson’s alcoholism was undoubtedly exacerbated by her dramatic personal life in which she grappled with a love triangle between herself, Diamond and her husband, Reeves McCullers. Additionally, she lived as a closeted lesbian for most of her life. In the 1950s, she discussed her sexuality with therapist Dr. Mary A. Mercer and alluded to her orientation in her final, unfinished work of fiction, The Exquisite Psycho. In one scene published by John Dalmas many years after her death, aged 50, in 1967, a character named Camille says, “I wonder if that’s my real problem. Wonder whether I am bisexual. If that’s true, it might solve a lot of problems.”

[embedded content]