The absurd story of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s fake execution

Posted On

Posted On

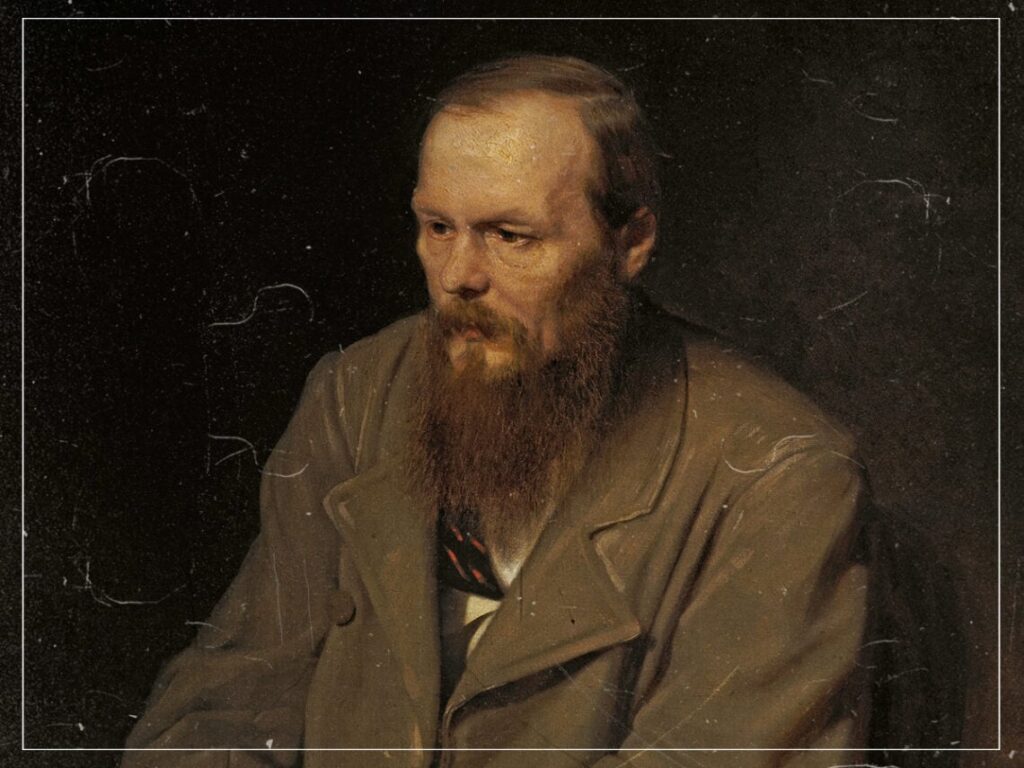

(Credits: Far Out / Vasily Perov)

Fyodor Dostoyevsky is often referred to as the progenitor of existentialist literature. This is mostly, but not exclusively, in reference to his 1864 novella Notes from Underground. This bleak exhibition of the Underground Man’s psyche against the backdrop of 19th-century St. Petersburg was precursory to 20th-century masterpieces of existentialist fiction, especially those by the French writers Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Developing ideas probed by Dostoyevsky, Camus was fixated on the absurdity of existence and explored how people from different ethical and religious backgrounds react to these absurdities. His most consummate exploration of absurdism was 1947’s The Plague, wherein a troublesome pestilence sweeping the fictional French city of Oran allegorised the rise of fascism in Europe during World War II.

Dostoyevsky’s life was plagued by tragedy and misfortune, but his reaction to it allowed him ultimately to succeed and prosper from his suffering. From an absurdist point of view, the universe is an ungovernable and irrational mass, and our existence in it is of little meaning or consequence. An absence of religion can be regarded with fear, but absurdism embraces the universe’s dispassionate will and can bestow certain liberties.

Contrary to absurdism, Dostoyevsky embraced Orthodox Christianity but paved the way for Camus through his philosophy regarding human suffering. “Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart,” he famously wrote in the 1866 novel Crime and Punishment. “The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on Earth.”

In his final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky attributes human suffering to the will of God. Although he concedes that this suffering can never be redeemed, he posits at length that suffering can be a virtue, imbuing life with meaning and direction. As far as Dostoyevsky was concerned, a reaction to suffering maketh the man.

At the heart of Dostoyevsky’s life and major literary works was a crucial period of suffering. The novelist was arrested on April 23rd, 1849, for his involvement with the Petrashevsky Circle, a group of intellectuals who championed liberal and socialist ideas that were considered subversive by the Russian authorities at the time. More specifically, he was accused of criticising the armed forces, possessing an illegal printing press used to create anti-government propaganda, involvement in a plot against Tsar Nicholas I, and denouncing the Orthodox Church and Tsarist establishment.

For these treasonous crimes, the Tsar sentenced Dostoyevsky to death by firing squad. The writer stood face-to-face with mortality on December 22nd, 1849. Chained alongside fellow members of the Petrashevsky Circle, he knelt and kissed the cross, following execution customs before being tied to a pillar, blindfolded, to await the firing squad. Just as the tension reached a fever pitch, a messenger representing the Tsar arrived with a stay of execution. Subsequently, the convicts were sentenced to four years of hard labour in a brutal prison camp in Siberia.

Dostoyevsky’s exaltations are immortalised in a letter he wrote to his brother Mikhail just hours after the planned execution. “Why didn’t I face death for three-quarters of an hour today, live with this thought in my head, was I not a hairsbreadth away from death, and now I am living again,” he wrote. Adding, “I am being reborn in another form.”

It later transpired that the Tsar calculated this sequence of events in advance, hoping to torture the convicts with the fear of death, subsequently earning their gratitude and respect. Dostoyevsky was undoubtedly grateful for the gift of time. “When I turn back to look at the past, I think of how much time has been wasted, how much of it lost in misdirected efforts, mistakes, and idleness, in living the wrong way,” he wrote to Mikhail, conveying the impact of this abject absurdity. “However I treasured life, how much I sinned against my heart and spirit—my heart bleeds now as I think of it.”

“Life is a gift, life is happiness, each minute could be an eternity of bliss,” he concluded.

Sadly, this was far from the end of Dostoyevsky’s suffering. For four gruelling years, he endured the abject hardship of a Siberian prison camp before entering compulsory military service in exile for a further six. Unlike many of his fellow prisoners, Dostoyevsky survived, with freedom finally restored in 1854. He would reflect on this period of suffering in The Houses of the Dead, a semi-autobiographical novel published in 1862.

[embedded content]