Sun, sand, sex, and survival: the year that changed Australian cinema forever

Posted On

Posted On

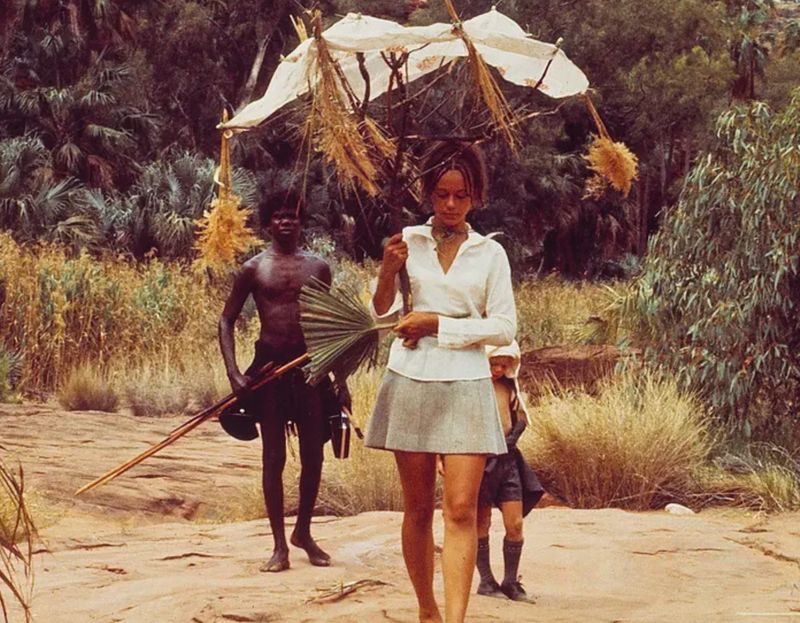

(Credit: YouTube still / 20th Century Fox)

While Australia may not immediately spring to mind when asked to think of the global contributions towards cinema in general, directors such as Nicholas Roeg, have produced some of the most captivating films of the Australian new wave era, which are now globally revered and paved the way for a shimmering cinematic renaissance.

A number of filmmakers throughout the early 1970s and mid-’80s became the recipients of increased government funding for the arts, allowing for bold and daring new voices to be translated onto the screen and spark the careers of directors like Peter Weir, George Miller and Bruce Beresford, going on to make films such as Picnic at Hanging Rock, Walkabout and The Cars That Ate Paris. However, while many of these projects later defined the future of Australian cinema, there were three films in particular sparking the rise in popularity of this genre.

The films of this persuasion were all concerned with similar themes and subject matter, exploring the intricacies of the modern world, our disintegrating respect for nature and the mistreatment of Australia’s Indigenous people. Many of these directors were posing important questions about our place in the world and the changing nature of humanity itself, encouraging audiences to reflect on these issues with their provocative and fearless storytelling.

However, one of the key movies from this era was Walkabout, directed by Roeg in 1971. The film follows two young siblings who are abandoned in the outback by their father, forging a friendship with an Aboriginal boy who teaches them the skills to survive in the harsh wilderness.

It is a uniquely hypnotic watch, with startling imagery that highlights the jaw-dropping beauty of the Australian outback, forcing us to reckon with the fact that we have destroyed something so special by distancing ourselves from the earth for the sake of progression, corrupting what is natural and making lives out of unnatural forces.

Walkabout was pivotal within this movement, along with two other films that were strangely released during the following three months of the same year.

Stork, directed by Tim Burstall, is rather different in tone, following an awkward man called Stork who finds himself in constant trouble as he struggles to maintain jobs and winds up the women around him . While it is light-hearted and distinctly unserious, it was crucial within this movement to create a rambunctious and sometimes charming portrait of counter-culture in Australia and a new dawn of creativity that was taking over, leading to whacky new projects/stories.

And lastly, Ted Kotcheff’s film Wake in Fright was the final film to spur on the success of this movement. The film follows a schoolteacher who visits a small mining town and joins in on their crazed obsession with gambling, leading to a five-day bender in the hopes of winning the money to move back to Sydney. It is highly nihilistic and oppressive, with the lead character stuck in a hell of his own making and exposing his failings as he desperately scrambles for a better life. Without all three of these films, the Australian New Wave would not be where it is today, carving out a strangely dystopian side of cinema that confronts issues ever-pressing today.

[embedded content]