‘Serial Mom’ and ‘To Die For’: When female criminality becomes camp

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Savoy Pictures)

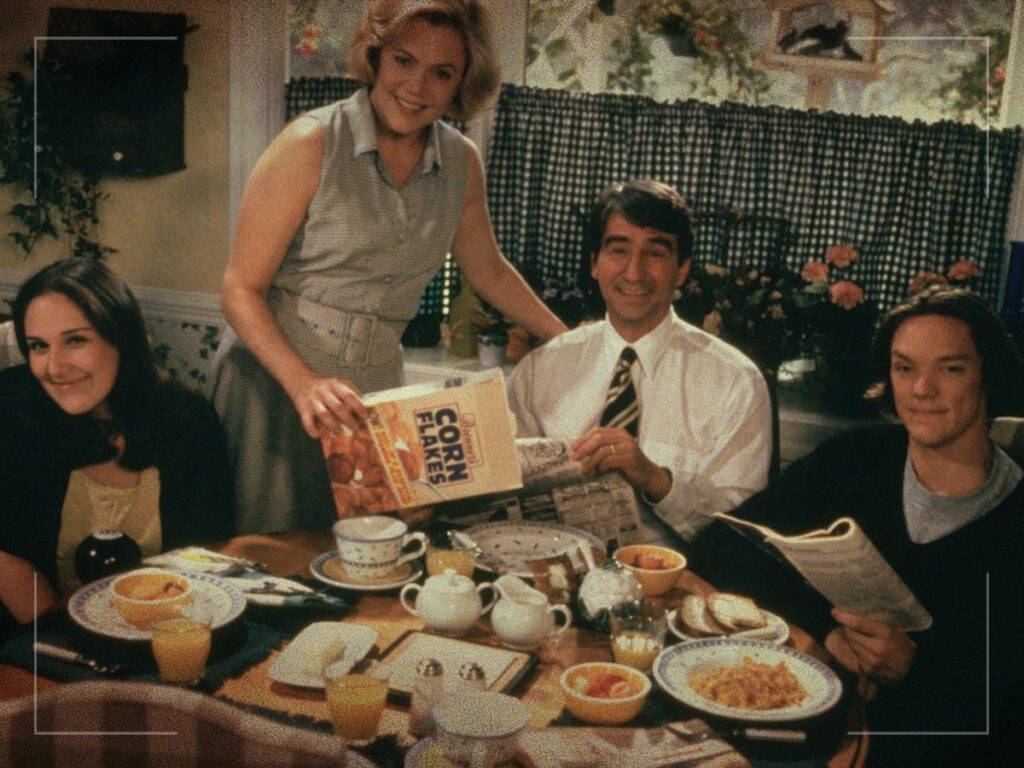

In 1994, John Waters released one of his greatest films, Serial Mom, in which Kathleen Turner gives an Oscar-worthy performance as a housewife with a taste for the macabre, killing anyone who wrongs her family members.

Just one year later, Gus Van Sant’s To Die For was released, with Nicole Kidman playing a woman who hatches a plan to kill her husband. Both films intertwined themes of celebrity and campiness with female criminality, emphasising a connection between gender and spectacle.

It’s no secret that most murderers tend to be men, with the percentage of female serial killers a considerably smaller number. Thus, by featuring female killers in the lead of each film, both played with an overtly over-the-top tone, there’s a real sense of detachment from reality at work. The rarity of women like Turner’s Beverley and Kidman’s Suzanne serves each movie’s approach to comedy, with the innate absurdity of their actions, like Beverley killing one of her victims with a leg of lamb, a prevailing theme.

Both movies would have arguably taken on much darker tones if the protagonists were played by men, and that’s because it’s a lot less funny to watch films featuring the kind of violence that affects countless women across the world every day. Yet, when Beverley burns a high-schooler to death at a gig in which the band are wearing giant vaginas, female criminality soon becomes camp.

In Notes on Camp, Susan Sontag defined the term as “not a natural mode of sensibility, if there be any such. Indeed, the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.”

Irony also plays a significant part in the formation of camp, and here, female killers are portrayed in an exaggerated way because it’s ironic – women rarely kill at the same rate as men. These women become caricatures of violent women; they’re not scary or truly threatening, at least not on the surface, and they take pride in their appearances as well-rounded (and well-groomed) members of society.

Additionally, fame shapes each woman’s narrative, with each film revealing the heightened world of celebrity as fake and vacuous. In Serial Mom, Beverley soon becomes the hottest celebrity of the moment, gaining superfans who follow her every move and advocate for her innocence, while Suzanne’s desire for success as a television star leads her to have her husband killed when it becomes clear that he is only a hindrance to it. Both movies show how enticing yet damaging fame and celebrity can be, satirising the way that people will go as far as committing heinous crimes to achieve worldwide recognition, enjoying the feeling of being adored by others, regardless of why.

The satire that informs Serial Mom and To Die For questions the general public’s interest in murderous figures, especially when the person guilty of the crimes is someone you wouldn’t expect. In the latter, Suzanne’s quest for celebrity stardom includes seducing a high-schooler to kill her husband for her, and Van Sant pulls this off with perfect levels of satirical dark comedy. Suzanne is incredibly ambitious, and you’d never tout her as the murderous kind, but in Van Sant’s world, anything is possible.

In real life, female criminality certainly isn’t camp. Murder is not camp. Yet, it is such a unique phenomenon – how has a woman, perhaps a mother, become a cold-hearted killer? – that naturally attracts the public’s attention, and the seeming ‘unnaturalness’ of it lends itself to the camp cinematic framework. Dark and outrageous, these films deliver poignant social commentary on fame, gender, and criminality, leaving us to wonder when we draw the line.

When do we start or stop empathising? Should these movies be as funny as they are? And would these films take on the same camp sentiment if the protagonists were male?

[embedded content]

Related Topics