Pivoting on a dime: 10 scenes that completely changed entire movies

Posted On

Posted On

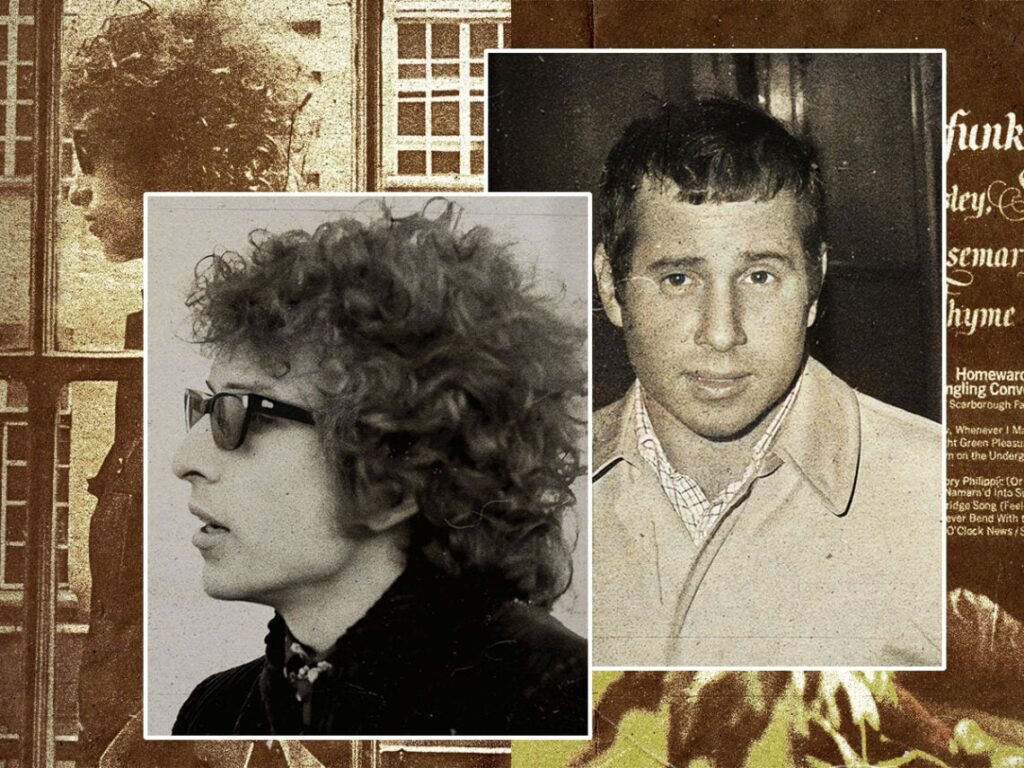

(Credits: Far Out / Miramax Films / YouTube still)

There’s no rule that says any movie has to pick a style, tone, or even genre and stick to it from the first to last scene, with many subversive filmmakers having changed things up at the drop of a hat. From Burn After Reading to Hot Fuzz, some of the finest movies of all time have you positing the question, “What genre is this again?”

On other occasions, all it takes is a single scene to completely alter the landscape of a character, plot thread, or entire film, and it always works best when the audience doesn’t even see it coming. Alas, it’s not easy to pull the rug out from under the audience.

When it backfires it can come across as a cheap gimmick, but that wasn’t the case when the following ten filmmakers decided that right when viewers were getting comfortable with what they were seeing, it was the ideal time to toss the rulebook out of the window.

It isn’t always flawless, but when it works, it really works. Mileage may vary, of course, but it can’t be argued that these flicks were never the same once they deployed their game-changing moments that completely flipped the script.

10 scenes that completely changed entire movies:

10. Sunshine (Danny Boyle, 2007)

A single scene completely changing a movie isn’t always a good thing, with Danny Boyle making the ill-judged call to suddenly turn Sunshine from an existential drama into a cosmic serial killer thriller.

The first two-thirds of the movie are excellent, with the stellar ensemble cast displaying the gravity of their situation when it begins to dawn on them their last-ditch mission to reignite the Sun and save humanity may well be doomed.

Switching gears to its detriment, the introduction of Mark Strong’s charred antagonist Pinbacker takes Sunshine in a completely different direction that renders it unrecognisable from its former self, sucking all the wind out of its sails for a formulaic final act.

[embedded content]

9. To Live and Die in L.A. (William Friedkin, 1985)

The audience surrogate is one of cinema’s most tried-and-trusted practices, giving viewers a way into the story by retelling the events contained within from the perspective of the main character. However, William Friedkin wasn’t in the mood for playing ball.

Michael Greene’s Jimmy Hart helps foil an assassination attempt on the president, and takes his next assignment staking out a warehouse in the desert alone to keep an eye on potential counterfeiters. Suddenly, he’s off the table, rendering the prototypical notion of the audience surrogate obsolete.

Does that mean To Live and Die in L.A. is now the story of William Petersen’s Richard Chance? Hardly, with Friedkin revelling in using a single scene to create a sense of doubt and unease that’s pivotal to the rest of the film.

[embedded content]

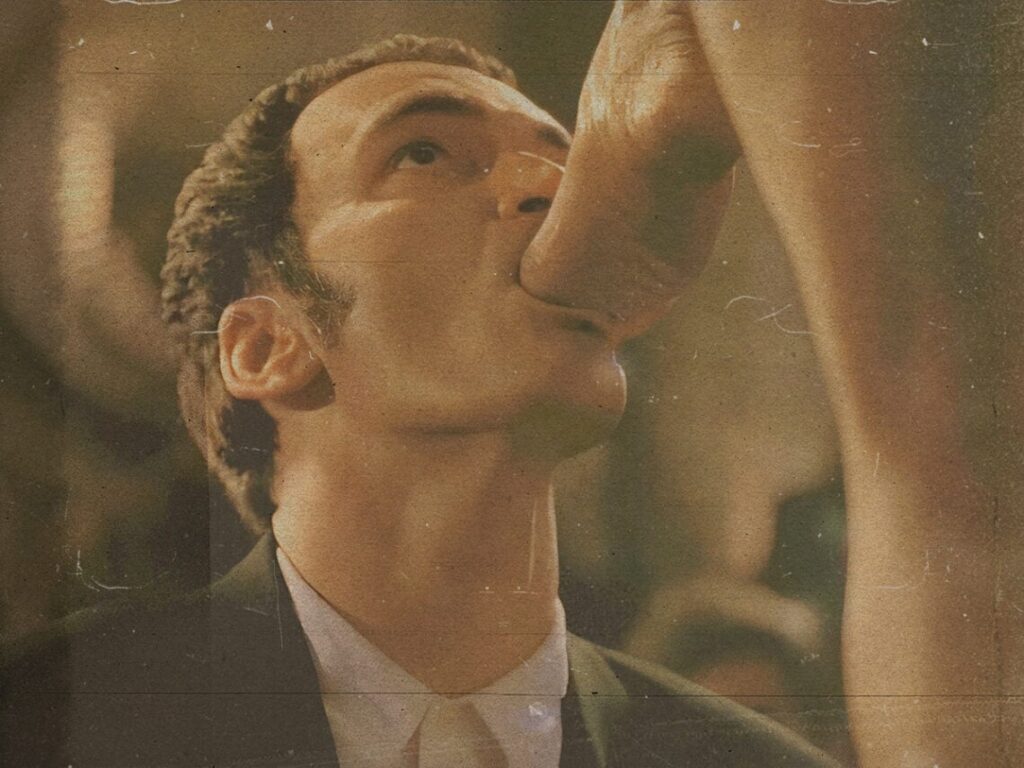

8. Seven (David Fincher, 1995)

No, it’s not the head in the box scene, but it is another sequence featuring Kevin Spacey as cold and emotionless serial killer John Doe.

Conventional wisdom dictates that in the realm of the serial killer thriller, the dogged detectives on the hunt for the murderer in question will spend the first two acts playing catch-up before it builds towards a climactic showdown where they get their perpetrator.

However, Spacey – who went unbilled and unmentioned in the pre-release build-up – simply waltzes into the police station midway through and turns himself in. In a moment, all bets were off as to what could come next, with Doe clearly having more tricks up his sleeve after willingly giving himself up to the authorities.

[embedded content]

7. One Cut of the Dead (Shin’ichirō Ueda, 2017)

Horror tends to be at its best when operating on multiple levels, but rarely has it gone further through the looking glass than on One Cut of the Dead.

The story appears to be that of a Japanese film crew tasked to shoot a shoestring zombie movie in a single take, with the first third unfolding as a solitary tracking shot. Once the penny drops, though, the movie delivers a mind-blowing bombshell.

The credits begin rolling, indicating that the genuine narrative of One Cut of the Dead is actually about the film crew who made the movie depicted in the opening stretch, with that film-within-a-film-within-a-film mindfuck utterly upending every shred of expectation created up until that point.

[embedded content]

6. The Usual Suspects (Bryan Singer, 1995)

Sure, it’s more of a twist than a single scene that alters the complexion of an entire movie in one fell swoop, but who says they can’t be one and the same?

For the majority of its running time, Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects is a razor-sharp comedic crime thriller coasting on the back of Christopher McQuarrie’s Academy Award-winning screenplay, hinging on the central mystery of who Keyser Söze is and what he wants.

Suddenly, though, the story is recontextualised as being told from the perspective of the most unreliable narrator imaginable. At that moment, it’s entirely OK to pause The Usual Suspects and ruminate for a minute or two over everything to have just unfolded, because every frame instantly carries a new and different meaning.

[embedded content]

5. Gone Girl (David Fincher, 2014)

It might have been based on a bestselling novel, therefore, there were plenty of folks who knew exactly what to expect heading in, but for anyone unfamiliar with the source material, David Fincher turned their world upside down.

What was once the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Rosamund Pike’s Amy Dunne has now become a psychological pot-boiler, with the missing spouse of Ben Affleck’s Nick not only alive and well, but the orchestrator of her own ordeal.

It’s a masterful bait-and-switch that immediately changes the loyalties, allegiances, and perceptions of both the characters in Gone Girl and the viewers who were formulating their own opinions of them, with Amy’s reign of terror having not even begun.

[embedded content]

4. Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

Completely intentional it may be, but David Lynch clearly revels in deliberately obscuring precisely what was so… off… about Mulholland Drive‘s warped reality until the Club Silencio scene.

Questions were being asked about the blurred lines between the real and the fantastical from the very beginning, but this was the exact moment where Lynch laughed openly the face of answering any questions without posing several more.

Before Club Silencio, Mulholland Drive had been careful not to get too definitive about where one reality ended and the next began, until the filmmaker finally offered the most explicit confirmation that the answer may well be everything.

[embedded content]

3. Parasite (Bong Joon-ho, 2019)

Bong Joon-ho has shown himself to be adept at any genre he turns his hand to, so in hindsight, maybe it wasn’t all that surprising his ‘Best Picture’ winner turned everything on its head with the ring of a doorbell.

Explorations of class and wealth inequality have always been key to the director’s work, so there was nothing overtly out of the ordinary as he examined the wildly disparate existences of the Park and Kim clans through the lens of a deliciously dark comedy.

It’s not an accident that it occurs exactly halfway through the film, either, with Parasite forsaking its established tone in favour of taking a much darker and even more subversive turn.

[embedded content]

2. From Dusk Till Dawn (Robert Rodriguez, 1996)

Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez might be best buddies and nameworthy directors, but they also have completely different stylistic and thematic approaches to their work.

When they put their heads together and had the former writing and the latter of directing, it probably should have been obvious that From Dusk Till Dawn was going to be far from a straightforward affair.

The first half is all Tarantino with its crime thriller stylings and endlessly quotable dialogue, but once the gang takes their seats at the Titty Twister, the first sight of blood gives rise to a bonkers splatter-fest of vampiric insanity.

[embedded content]

1. Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

They didn’t call him the ‘Master of Suspense’ for nothing, Alfred Hitchcock went out of his way to ensure audiences couldn’t watch Psycho on the big screen unless they were seated before it started.

Star Janet Leigh was a big name who’d been the focal point of the marketing, and the norm had convinced everyone that Psycho would follow her Marion Crane as she did her best to survive the bloodthirsty murderer lurking in her midst.

Of course, in one of the genre’s most iconic scenes, Marion ended up taking the stabbiest shower imaginable to pull the rug from right under everyone to refit Psycho as a whodunit with an even more sinister twist to come.

[embedded content]