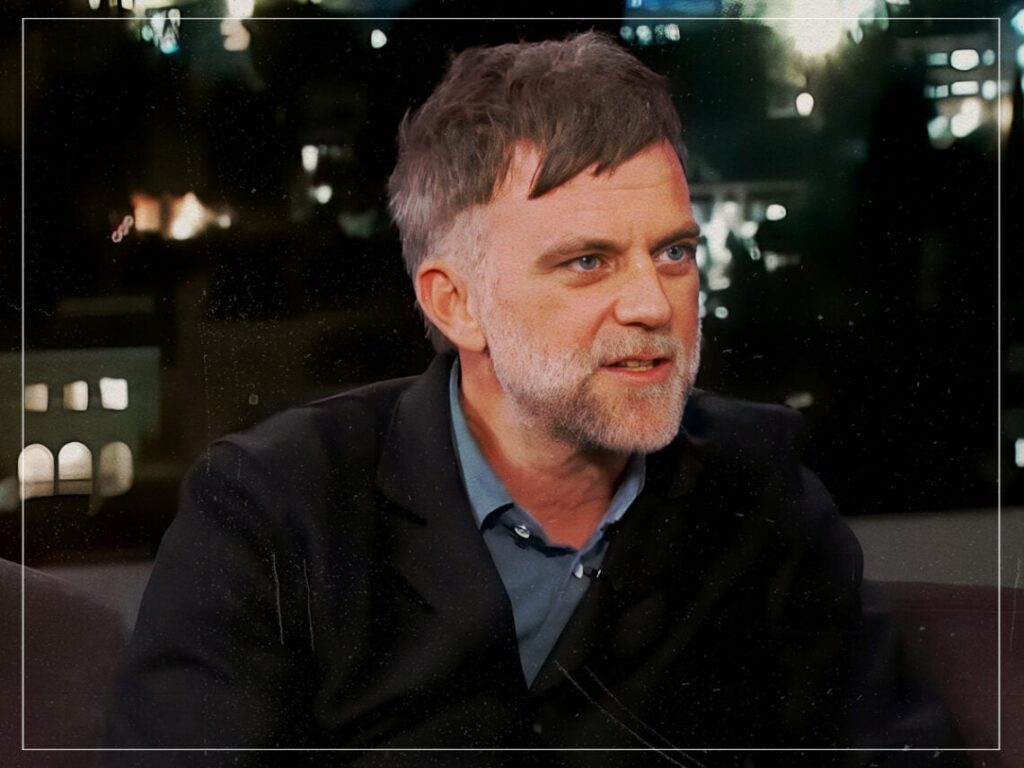

Paul Thomas Anderson explains how to draw a great performance from an actor

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / YouTube Still)

Born in Los Angeles’ Studio City, Paul Thomas Anderson’s future as a filmmaker seemed secure from the get-go. He grew up just a short drive away from Hollywood and had a father involved in the entertainment industry, clearly finding himself attracted to this opulent and enticing world.

After he started making films as a child, he knew he wanted to be a filmmaker, subsequently making his first feature, Hard Eight, in 1996. While it was successful, he found much greater acclaim with Boogie Nights, released the following year, which contained an impressive cast, including Burt Reynolds and Philip Seymour Hoffman. He also recruited John C. Reilly, who he had cast in Hard Eight, while Hoffman and Melora Walters had also appeared in the filmmaker’s debut.

A common theme throughout Anderson’s movies is the use of actors he’s previously collaborated with. It seems as though when he finds an actor who really understands his style and approach to filmmaking, he’ll use them again and again. This is often the case for directors who consistently work with ensemble casts, from Robert Altman to Quentin Tarantino.

Anderson is no exception, with his most frequent collaborators including the late Hoffman, Daniel Day-Lewis, Julianne Moore and Joaquin Phoenix. His repertoire of actors is also impressive, and most of his most beloved stars are Oscar winners or held in incredibly high esteem. The performances within Anderson’s films, from Day-Lewis’ breathtaking turns as Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood and Reynolds Woodcock in Phantom Thread to Hoffman’s Lancaster Dodd in The Master, are always astounding.

Thus, fans often wonder how Anderson manages to capture these performances, but he is adamant that the most important factors are the actor’s pre-existing talent and “scheduling”. Talking to The Film Pie, Anderson explained, “They’re pretty great without me. You can write a scene really well and do all the other traditional things that get you there but you’d be surprised how much of a contributing factor scheduling can be.”

He added, “A performance can be like an athletic event. If you’re asking someone to come in and deliver something, it takes a high degree of concentration and physically takes something out of them. It’s as small and as incremental as managing hour-to-hour what they’re doing and what they’re up against.”

For Anderson, making the workload as efficient and easy to manage as possible is considerably more effective. “Sometimes an actor will go and do a film and the director won’t tell them how many shots they’re going to need to do a scene. So they have to spend an enormous amount of energy in anticipation of what may be asked of them rather than being clear about how to schedule the day,” he continued.

Being able to preserve energy, rather than waste it all and drain it before it’s required for a harder scene, is vital for getting the most out of the actors. “It helps you invest in what you’re doing and not just throw a bunch of things at the wall and overcrowd it and get tired and grumpy and sick of making a movie,” Anderson concluded.

[embedded content]