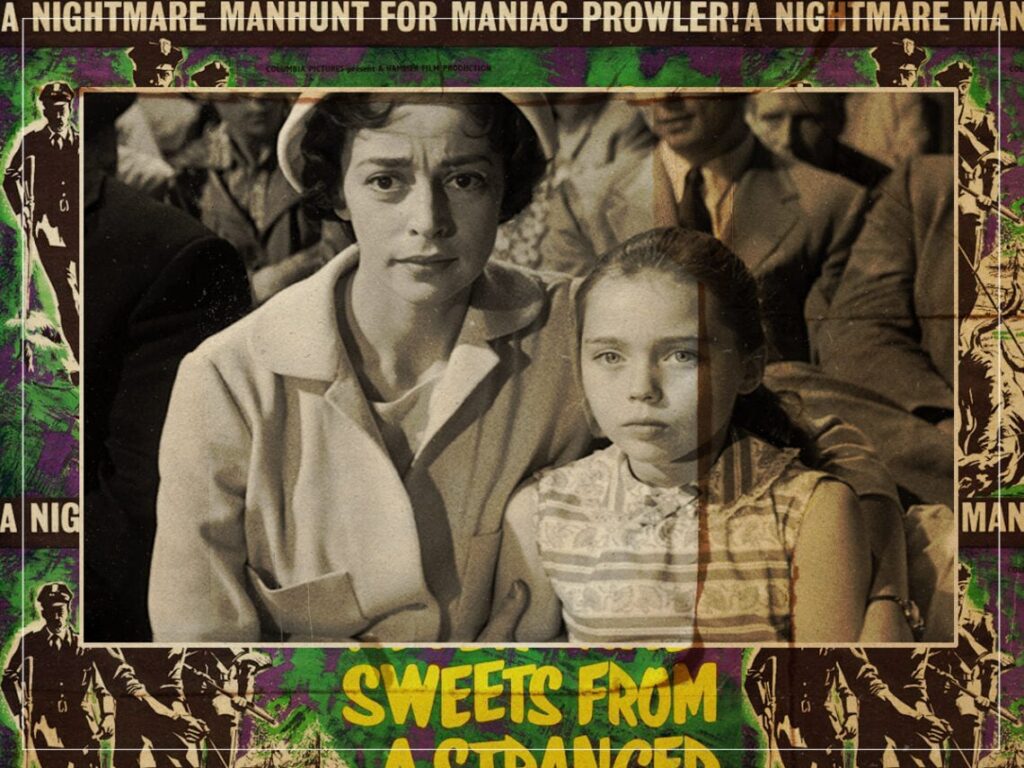

‘Never Take Sweets from a Stranger’: Hammer’s haunting non-horror

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Hammer Films)

Mention Hammer Films to anyone, and their mind will instantly wander to the succession of horror movies that became the studio’s bread and butter for decades, which is perfectly understandable when that’s what made the company such a well-known brand in the first place.

The outfit had dabbled in whatever genre took its fancy from the moment it was formed in 1934, but Hammer reached the peak of its popularity by way of terrifying tales. Christopher Lee’s Dracula helped usher in the golden years in 1958, and for the next two decades, horror formed the overwhelming majority of the production house’s catalogue.

In fact, it was the single most prolific entity in British cinema throughout the 1960s, which inevitably caused many titles to be overlooked, ignored, or neglected because they didn’t feature a monster stalking through the shadows in search of its next victim. However, there was plenty of irony to be found in Hammer’s most haunting movie not even being horror at all.

Instead, it was a dramatic thriller, which doesn’t leap out as an obvious candidate when audiences were up to their eyeballs in vampires, mummies, Frankenstein, ghouls, beasts, zombies, creatures, and whatever else required actors to be stuffed into costumes and slathered in makeup. And yet, Never Take Sweets from a Stranger was truly chilling.

Going against the grain of Hammer’s outlandish output and tackling taboos that had rarely been depicted in a mainstream motion picture, director Cyril Frankel used Roger Garis’ play The Pony Cart as the jumping-off point to craft a movie so out of left field and unexpected that no less of an authority than erstwhile studio figurehead Lee told the Sarasota Herald it wasn’t just years, but “decades ahead of its time”.

Hammer – and the films it made – were very much of their era, satiating the increase in bloodlust and loosening inhibitions to double down on things going bump in the night and scantily clad women. That was exactly why Never Take Sweets from a Stranger came completely out of the blue, because it hinged its entire narrative on a subject that was scarcely told on celluloid.

A family of British expatriates relocate to a small Canadian town after the patriarch is appointed the principal of a local school, only for a scandal to emerge when Felix Aylmer’s Clarence Olderberry Sr – a member of the wealthiest and most powerful clan in town – is accused of being a paedophile and trying to coerce minors into acts that constitute child sexual abuse.

The local police chief casts doubt on the allegations made by Peter Carter’s young daughter, Jean, while Clarence’s son threatens to discredit them and ruin their lives if the matter goes to court. It does, only for the Carters to find themselves up against a stacked jury that leads to a swift acquittal.

It may have been tossed out of the courtroom, but the story doesn’t end there, with Never Take Sweets from a Stranger repeatedly returning to its overarching theme of corruption, whether it’s being applied to power or innocence. It was unlike anything Hammer had made before and went on to produce after, with the storyline alone enough to make it the company’s most unsettling movie.

[embedded content]

Related Topics