‘Metropolis’: The sci-fi movie H.G. Wells called “hopelessly silly”

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Picryl / LSE)

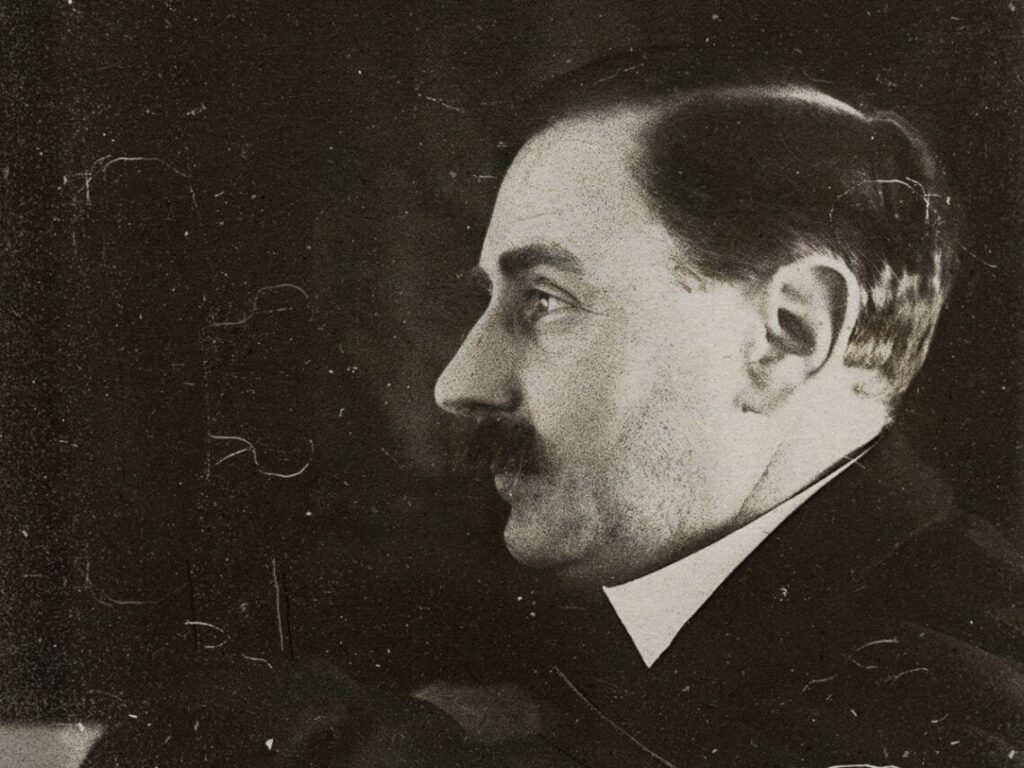

It’s not unreasonable to expect one of the most influential sci-fi writers of all time to enjoy one of the greatest sci-fi movies ever made, but that didn’t turn out to be the case when H.G. Wells first laid eyes on a film that would go on to become regarded as a cinematic landmark.

As the author of The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The War of the Worlds, and The Invisible Man, among others, Wells cast a massive shadow over the genre on both the printed page and the silver screen, with his works being adapted and repurposed for film, television, and radio to this day.

The impact he had on sci-fi as an author is similar to the one made on motion pictures by Fritz Lang when Metropolis released, with the 1927 epic a labour of love that took 17 months to shoot. Initially greeted with a muted reception and criticisms of its exorbitant running time, the trailblazing and game-changing film has long since been regarded as one of cinema’s most important works.

Christopher Nolan, the Wachowskis, the Coen brothers, Tim Burton, Quentin Tarantino, Terry Gilliam, Ridley Scott, and George Lucas are just a sampling of the notable directors to have either voiced their admiration for Metropolis or confirmed its influence on at least one of their features if not more, but Wells was left remarkably nonplussed by what he saw.

In fact, in a review written around the time of its release, the formidable forefather of sci-fi was nothing short of scathing. “I have recently seen the silliest film. I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier,” he wrote. “And as this film sets out to display the way the world is going, I think The Way the World is Going may very well concern itself with this film. It is called Metropolis, it comes from the great UFA Studios in Germany, and the public is given to understand that it has been produced at enormous cost.”

Offering that Lang’s masterpiece offers “almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general”, he found the Metropolis to be “served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own”.

“Originality there is none. Independent thought, none. It is immensely and strangely dull. It is not even to be laughed at,” Wells continued, effectively brandishing a stone-cold classic as unoriginal, derivative, boring, humourless, and outright stupid. Everyone is entitled to their opinion, but the reputation of Metropolis relative to the entirety of cinema history firmly places Wells in the minority.

Of course, he was vastly qualified to offer his thoughts on a genre he brought to new heights, but such a damning indictment of Metropolis coming from a sci-fi savant-like Wells was nonetheless entirely unexpected.

[embedded content]