Kneecap: “If art can court controversy, that’s a good thing”

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Kneecap)

Since the days of Elvis Presley in the 1950s, music and controversy have been locked in a marriage of convenience. The industry line has become more prevalent in recent years, but the Irish hip-hop trio Kneecap are here as disruptors who love nothing more than ruffling feathers and creating headlines.

Since their formation in 2017, Kneecap has courted criticism from right-wing politicians, namely the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland. Now, they are currently engaged in a legal battle with the British government, which prevented them from receiving funds as part of a scheme to promote homegrown music overseas.

While the group is proud to be Irish, rap in their mother tongue, and fly the tri-colour flag at every available opportunity, their taxes go into the British system. However, in the eyes of Conservative MP Kemi Badenoch, this isn’t enough to make the group deserving of funds.

Underneath the stunts and attempts to piss off members of the DUP, Kneecap are merely using music as a vessel to explain their life as young adults in Belfast, which is relatable to people on both sets of the religious divide in the city. Appropriately, their debut album, Fine Art, is set in the fictitious pub, The Rutz, which acts like a fourth band member on the record.

Fine Art is a tale of a well-spent youth that saw them escape the banal realities of life with the aid of alcohol and drugs while also paying homage to the Irish rebel music upon which they were raised.

Sheffield beat-maker Toddla T was tasked with producing Fine Art, which they completed in only a fortnight. Meanwhile, the producer’s wife, Annie Mac, also plays a part as a narrator across the record. Toddla T’s involvement not only elevated their sound, but for Mo Chara, it “gave us legitimacy” in the music business.

The collaboration with the Yorkshireman occurred naturally, as Móglaí Bap says over Zoom as he huddles around a laptop screen next to his bandmates Mo Chara and DJ Próvaí, noting that they’d “heard through the grapevine” he was a fan. Eventually, he secured Toddla T’s number. They were in the studio two days later and recorded the title track in three hours, which sowed the seed for the entire record.

Chara says the collaboration has stopped people seeing them as a “token Irish language band” or a “parody”, which he thinks occurred because they don’t fit into the typical hip-hop mould. He explains: “The world of hip-hop is so braggadocious and always talking about violence and really masculine stuff, whereas we’re coming along and talking about owing paramilitaries money, so we’re gonna raid your granny for money.” After Móglaí Bap jokingly intervenes to declare their lyrics “deep stuff”, Chara finishes his bandmates sentence, adding, “proper deep James Joyce behaviour”.

In addition to finishing each other’s sentences, Kneecap also passed around a disposable vape pen between the three of them during our conversation, further saliva-drenched proof of their brotherhood, which was born in local pubs.

Using a fictional tavern as the setting for Fine Art was a simple choice for the trio, with Móglaí explaining, “For us, the pub in the epicentre of the craic and where we go and spend most of our social time.”

Nightclubs have never interested the trio, as “it’s not a good environment for trying to talk all night,” which is their favourite pastime. The pub, on the other hand, is a place they say accommodates “all walks of life,” and over the course of the album, listeners meet a spectrum of characters who may frequent this kind of homely establishment.

Representing Irish culture is vital to Kneecap, whether by including a traditional folk song on the record or rapping in their native language. Before the group took off, Provaí was an Irish teacher in a school, and through music, he’s playing a role in its resurgence. “When colonialism happened, they tried to separate the people from the language,” he passionately states. “That’s the first thing that colonial powers do, so you’re disassociated from your land and your identity. We’re trying to reclaim that, and the Irish language cultural revival has been happening over the last 100-odd years.”

Móglaí adds: “I think people feel a lot more seen, in terms of their identity, the young people in the cities and rural areas who speak Irish and they’ll go out partying, and now there is music that represents how they feel. When there’s a cultural revival, it happens on many different fronts, and we cater on the one front, which is debauchery in a pub.”

The video for the lead single, ‘Better Way To Live,’ was shot in Madden’s Bar in Belfast, a favoured hotspot for Kneecap. The track, featuring Grian Chatten of Fontaines D.C., captures the essence of the record as the band deals with the highs and lows of being stuck in a never-ending cycle of boozy nights, a tale familiar to many.

‘Better Way To Live’ has an addictive nature, with Chatten providing the perfect foil for Kneecap’s tenacity, but it also showed there was more to the trio than they previously expressed. “I feel like that really solidified us to those on the fence who thought, ‘Oh, they’re just being spoken about because they rap in Irish’,” Chara says proudly.

However, getting the track over the line was challenging because Chatten didn’t own a mobile phone. Ultimately, they had to send a driver to pick him up in Brighton as public transport wasn’t working, but eventually, the frontman arrived at the studio to nail the hook that Móglaí penned for him.

Despite both Fontaines D.C. and Kneecap playing at Glastonbury, the group play down the chances of Chatten performing with them at Worthy Farm “unless they send another driver” as he’s “impossible to contact”.

Kneecap’s eponymous biopic will also be shown at Glastonbury before a wider cinematic release. It was celebrated at Sundance with the ‘NEXT’ award earlier this year, and Sony picked up the distribution rights at the event. Additionally, in true style, Kneecap used the opportunity to court headlines by arriving at the premiere in a Northern Irish PSNI Land Rover, which was spray-painted over with their moniker, and like anything they do, it caused the DUP to lose their minds.

“Essentially, we have a symbiotic relationship with the DUP,” Chara says of the band’s political enemy. “We do a stunt, the DUP get pissed off. They get their chance to go on the media, go on the news and talk about it so they can become relevant again for a while. So, the DUP have us to thank and also, I would like to wholeheartedly thank the DUP for the PR,” he adds with a knowing smile.

The DUP aren’t the only political party that Kneecap have rubbed up the wrong way. After being included in the Music Export Growth Scheme, which would have provided them with £15,000 to enhance their profile abroad, it was vetoed by UK’s Business and Trade Secretary, Kemi Badenoch, who said, “We don’t want to hand out UK taxpayers’ money to people that oppose the United Kingdom itself.”

Although this would have caused many artists immense issues, Kneecap saw it as a gilt-edged chance for publicity and an opportunity for a PR campaign that would cost significantly more than the £15,000 they were due to receive.

While they “can’t say much about it because it’s an open case”, Provaí states, “We pay taxes to the United Kingdom against our will, and by that idea, we shouldn’t have to pay taxes if we’re not able to benefit from the taxes that we pay.”

Móglaí labelled it “USSR-type politics,” claiming the government is only willing to subsidise art if it “aligns with our politics.” He adds, “That’s basically what they’re saying, and I think it’s a bad precedent to set for art in general.”

Admittedly, the government’s intervention with art is a worrying development. However, the rapper knows it’s bought them more publicity than they could have landed for £15,000, “The same as the DUP, they’ve done the opposite as they wanted. They tried to condemn us and thought it would stop us, but really, it put us in the headlines.”

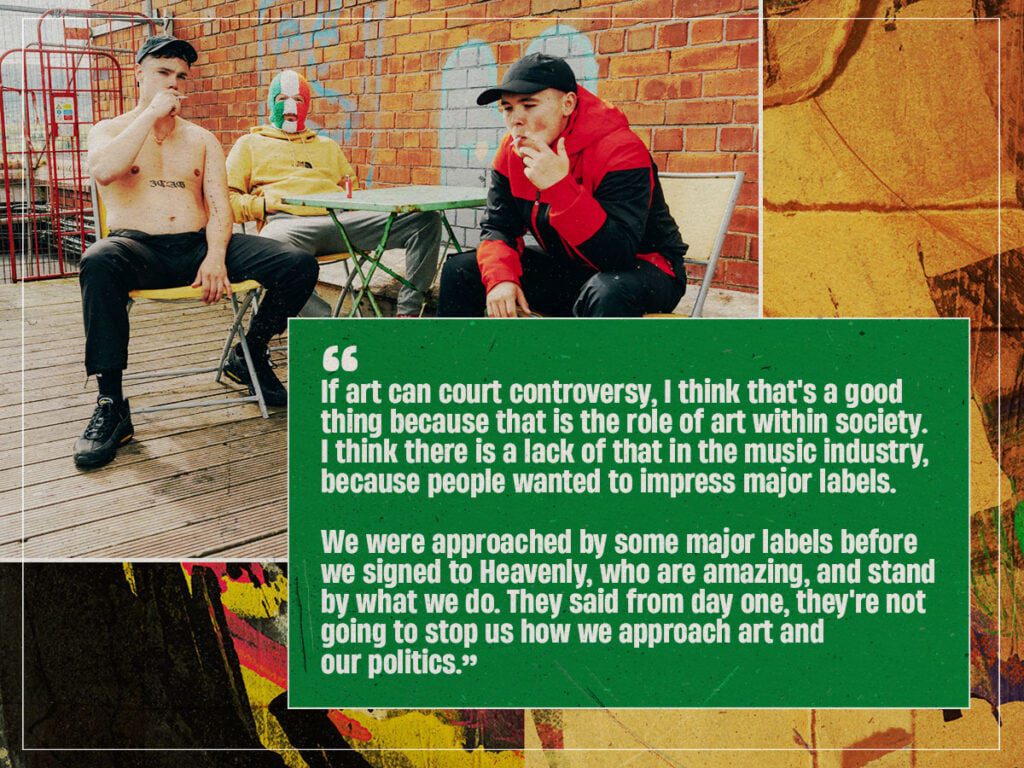

“If art can court controversy, I think that’s a good thing because that is the role of art within society,” Móglaí eruditely adds. “I think there is a lack of that (controversy) in the music industry because people want to impress major labels. We were approached by some major labels before we signed with Heavenly, who are amazing and stand by what we do. They said from day one, they’re not going to stop us how we approach art and our politics.”

Having this creative free reign is at the heart of Kneecap’s success. Once an artist gets into bed with a financial backer, whether for a film or an album, they naturally present a more palatable version of themselves to appease stakeholders’ interests. In an increasingly vanilla musical landscape, with artists afraid a slip of the tongue will result in their cancellation, Kneecap remain committed to provocation. Vitally, they are also smart enough to realise controversy is the oldest marketing tool in the book.

Fine Art is available through Heavenly Recordings now.