“Imitation leads to certain disaster”: the pioneering efforts of photographer Gertrude Käsebier

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Gertrude Käsebier / Wikimedia)

When photography started to become a popular medium, humans were amazed by the fact that people, places and events could be captured and immortalised forever. A few years later, however, the potential for photography to be used to create pieces of art – stylised, edited and manipulated – was realised. The Pictorialism movement championed the idea of photography as a mode of artistic expression, with Gertrude Käsebier becoming one of its leading advocates.

Born in Iowa, the photographer moved around the United States quite a lot as a child, eventually settling in New York, where she married the businessman Eduard Käsebier. After raising a family and eventually separating from her husband, she realised that she wanted to study art, so she attended the Pratt Institute of Art and Design. She was almost 40 by this point, proving that it’s never too late to pick up a new hobby or career path.

Käsebier learnt many photographic techniques during this time, which were vital in helping her approach the medium with art in mind. She once said, “The key to artistic photography is to work out your own thoughts by yourselves. Imitation leads to certain disaster.”

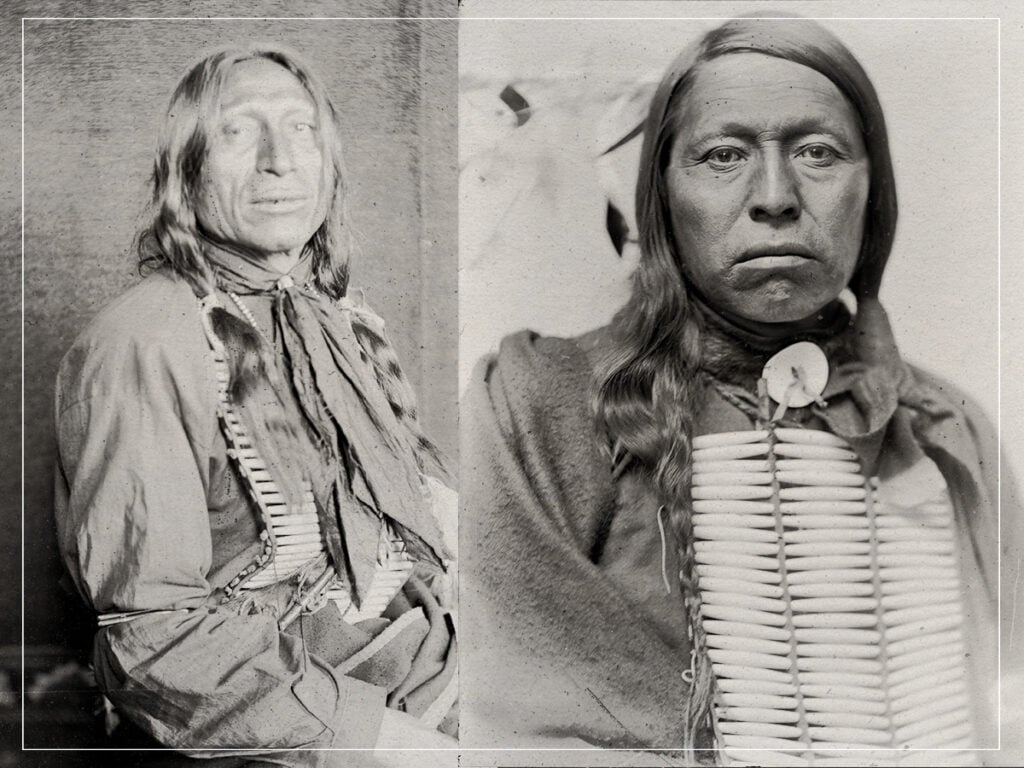

She became known for her portraits, often seeking to capture her subjects intimately, offering up a depiction of certain people that otherwise wouldn’t have been presented to the public. She was interested in Native American culture and sought to photograph people belonging to the Sioux tribe. Käsebier had several prominent Native American figures sit for her, such as Chief Iron Tail, unconventionally asking her subjects to wear more casual clothing so that she could solely focus on depicting their personalities through facial expressions.

She also photographed other famous figures, such as Auguste Rodin, George Luks, Alfred Stieglitz, Evelyn Nesbit, and Rose O’Neill, asserting herself as an artist with an incredible gift for capturing people through a personal and revealing lens.

The photographer was interested in showing women in domestic settings, too, with artworks such as ‘Bless Art Thou Among Women’, ‘The Manger’ and ‘Mrs R’ depicting women attending to their children. These beautiful, hazy images are snapshots of the lives that many women experienced behind closed doors, with Käsebier seeking to capture the beauty of motherhood and femininity.

(Credits: Far Out / United States Library of Congress)

Käsebier also advocated for women to take up photography, believing it to be a medium which could be used as a mode of expression and a way for women to make money independently. She co-founded the Women’s Federation of the Photographers’ Association of America in 1910, one of the various associations she was part of across America and Europe. She formed friendships with other female photographers, such as Frances Benjamin Johnson, championing women in art. Käsebier ended up becoming one of the biggest photographers of her day, featuring in many exhibitions and photo journals, such as Camera Work.

The journal was published by Alfred Stieglitz, a friend who was initially close with Käsebier, harnessing similar views on photography. However, he couldn’t understand why she was so preoccupied with making money from her art, which caused them to drift apart. Clearly, Stieglitz couldn’t see that, for a woman during this time, being able to independently make money through art was revolutionary – of course, Käsebier was compelled by this vision of freedom and autonomy.

She died in 1934, and while Käsebier was recognised during her lifetime, her name is much less well known these days, with male photographers from the same period tending to dominate our discussions of the medium’s early decades. Yet, Käsebier made many significant contributions to photography, championing it as an art form and career prospect for women while creating many beautiful and indelible photographs in the process.