How the films of Adam Curtis explore sociopolitics and the structures of power

Posted On

Posted On

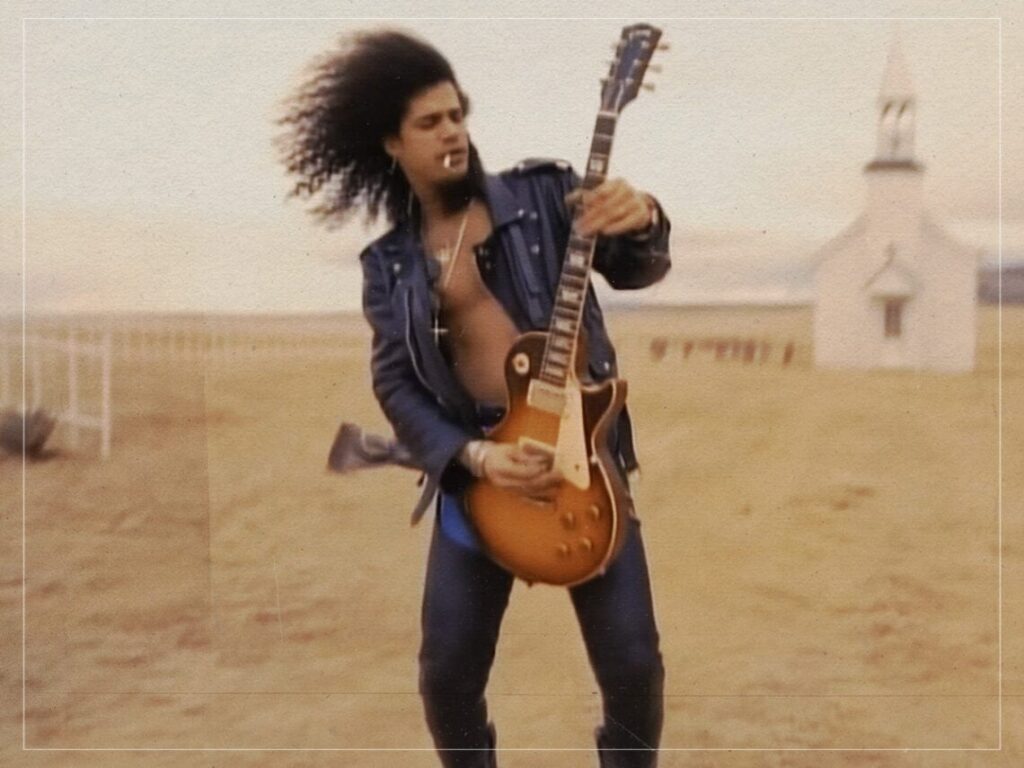

(Credits: Far Out / YouTube Stills / BBC)

The documentary works of British filmmaker Adam Curtis are deeply complex and brilliantly combine journalism, social critique, and more conventional documentary creation methods. Curtis has charted humankind’s modern history, explaining how past political and social events have undoubtedly influenced and formed our present.

In the 1980s, Curtis worked as a more straightforward documentary maker at the BBC. Still, when 1992 swung around, he detailed his trademark collage documentary style to dive headfirst into the realities of sociology, psychology, philosophy, and politics. Curtis’ films, including The Century of the Self, HyperNormalisation, and Can’t Get You Out of My Head, are not easy to watch by any stretch of the imagination. They can occasionally have a maddening, almost depressive effect.

After all, at the centre of Curtis’ focus is often the kind of hidden forces that invariably construct the societies that we live in. By fusing separate strands of culture and history, the Dartford-born filmmaker reveals striking patterns with a combination of artistry and social commentary.

Throughout his most notable works of film, he uses archival footage and ambient music from Aphex Twin, Board of Canada and Brian Eno to create a hypnotic, ambient mood, much like a serious iteration of Chris Morris’ TV comedy Jam.

However, when Morris’ intention had been to shock and titillate, Curtis’ approach is one that allows his rather difficult-to-follow narratives to assume a dreamlike quality, through which his suggestions of influencing forces are better understood. The most important of these is power itself and the way it has been assimilated throughout modern history.

A primary concern for Curtis is how governments, conglomerates, and media institutions use a psychological understanding of human behaviour to manipulate and control a wide range of their subjects. Of course, this kind of power only arrives in the hands of the powerful with method and reason, so Curtis attempts to show how it is gained, even though his arguments are beyond the average level of complexity found in standard documentary and academic discourse.

That very sense of complexity is a central facet of Curtis’ argument, as explored in 2016’s HyperNormalisation. In the film, Curtis posits that the real accrual of power is so far removed from the narratives that governments and corporations spin that there is often no alternative method of understanding, even though such institutions know they are indeed false.

What the world looks like for Curtis is a series of illusions spread through media, consumerism, technology and sociopolitical avenues of thought. The Century of the Self shows how psychoanalysis was used in advertising to exert more influence over populations, leading to a culture of self-worship and individualism, while All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace focused on the abandonment of collective social bonds as a result of the advent of modern technology.

What’s so admirable about Curtis’ films, though, is the way that his ideas are presented through his unique narrative style. The world itself often feels fragmented and distorted and Curtis does not shy away from presenting it exactly as it is, achieved through his archival footage collage that blends the past, the present and the future, aided by a calming yet rigorous narrative that invites us to question how we got to our present situation.

Adam Curtis pierces ideology and reveals the power structures hidden beneath our everyday lives. While such revelations can be shocking at best and world-shatteringly depressing at worst, Curtis asks us to consider the possibilities of an alternative future free from the shackles of the sociopolitics that dominate the human populace.

[embedded content]

Related Topics