How splashes on a wall made Jackson Pollock the most skilled draughtsman

Posted On

Posted On

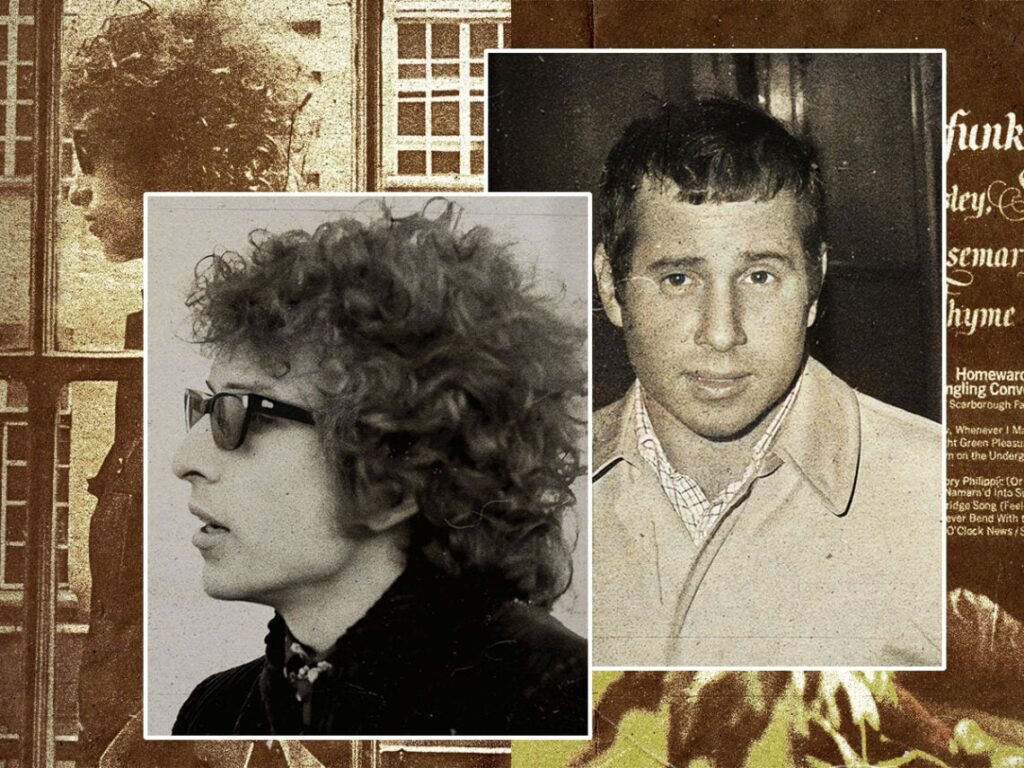

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy / Rob Corder)

Canvas painting after Jackson Pollock entered the art scene was never the same. That is how powerful Pollock’s work was, single-handedly transforming the trajectory of painting. If you thought Pollock’s paintings were simply nonsensical splatters of paint on a wall, closer to a 5-year-old’s drawing on a kitchen fridge than to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, then maybe I can convince you otherwise.

Pollock rose to fame in the 1940s and ‘50s while working in New York alongside other ‘Abstract Expressionists’, all wildly different from each other. Willem de Kooning was different from Mark Rothko, who was even more different from Clyfford Still. One loose thread did connect the group, however: in post-war America, Abstract Expressionism marked a watershed moment, a distinct rupture from the past that fragmented the Western artistic canon during the 20th century.

Painting well and truly was no longer about what you saw on the canvas but rather what you felt when you saw it. It was about experiencing what the artist experienced while making the canvas, not the final product.

You might argue that this technique didn’t make the abstract expressionists skilled draftsmen if what you are looking at is a melange of vomit-looking colours. But the very nature of the way we, as the viewer, become so connected with the artist through their act of painting is profound and genius. At that moment, art was no longer about aesthetic beauty, straight lines and porcelain skin but about sheer emotion, raw and wild.

Every artist worked differently, but Pollock placed his canvases on the floor and worked over them, taking full control of the space. He used oil and enamel paint, which provided two different effects, one more stain-like and the other richer and more opaque. You can observe this in the way that his “drip technique” has a watercolour effect, whilst other areas are more vibrant on top, adding multi-dimensionality to the flat canvas.

What many don’t know is that Pollock left us “bread crumbs” to find within his canvases. That’s right, he didn’t just use paint. Sure, it was the main medium and focal point, but if you observe closely, many of his works include squashed flies, cigarette butts and footprints, indicating he walked on the canvas.

In this way, we aren’t just seeing paint on a wall, but Pollock himself and his process of art-making. No preliminary sketches were involved; just direct movement and feelings were quite literally poured on the floor.

“Painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.”

jackson pollock

Photographer Martha Holmes created an exceptional series of photographs in 1949 for Time, documenting Pollock’s painting process. The series perfectly illustrates my point, as Pollock is the subject of the photographs, caught in the process of making, rather than the canvas. These photos are a representation of the artist not the artwork, and that’s what his paintings aim to do as well.

One: Number 31, from 1950, is one of Pollock’s most important canvases, spanning a whopping five by two and a half meters. The canvas had been wrapped around its stretcher, meaning it had no edges. Thus, the subject matter wasn’t confined to any space, rather it could bleed into its environment freely. We feel a sense of instability as we are engulfed into a canvas that exceeds the limits of boundaries and becomes part of the wall itself and our space.

Additionally, there are no formal rhythms or repetitions on the surface. Smears, splatter and blotches are all random and have no relationship with their neighbouring marks, highlighting the uniqueness of Pollock’s paintings that cannot be replicated nor the movement and dynamism involved in executing them. A striking opposition is set up between the art object, a static product of solidified paint, and the process of making it.

Pollock’s technique came to exemplify “Action Painting”, a term coined by the American philosopher and critic Harold Rosenberg. This idea removed any aesthetic concerns from the artwork, resulting in a canvas that showcases merely the residue of the making process. Simply put, Action Painting’s value is distinctly apart from the art itself.

This principle was built upon what Pollock defined his art to be, that is, centered around the primacy of the act itself. In a statement published in the winter 1947-48 issue of the avant-garde journal, Possibilities, Pollock said: “my painting does not come from the easel. I hardly ever stretch my canvas before painting…. On the floor I am more at ease. I feel nearer, more a part of the painting … and literally be in the painting… Painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.” Thus, Pollock considered himself as a mediator or messenger between art and viewer.

I invite you then to look beyond the immediate and open up your minds to explore and imagine what the painting process was like, not just seeing the canvas as the end point. As Rosenberg perfectly explains in his article “The American Action Painters,” published in December 1952, “what was to go on the canvas, was not the picture but an event”.

[embedded content]

Related Topics