How did Ludvig van Beethoven lose his hearing?

Posted On

Posted On

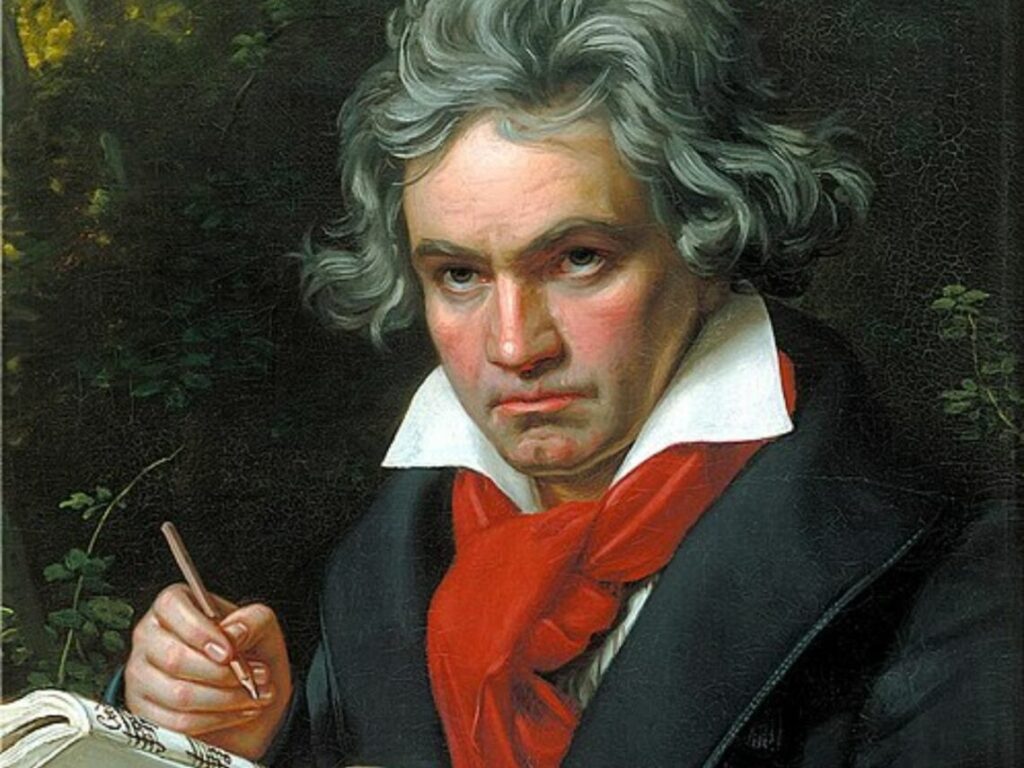

(Credit: Joseph Karl Stieler)

Long before they dominated leftfield rock music in the 1970s krautrock movement, the Germans sat at the forefront of musical evolution. With the exception of the eminent Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, many of the most renowned composers of the 18th and 19th centuries hailed from Germany, including Johan Bach, Johannes Sebastian Brahms, Richard Wagner, George Frideric Handel and the master Ludvig van Beethoven.

Those who have had the pleasure of watching Miloš Forman’s 1985 movie Amadeus will understand that, when it comes to classical music, it doesn’t get much more impressive than the Austrian child prodigy. Though the rivalry between Mozart and his Italian contemporary Antonio Salieri was largely fictionalised for dramatic effect, the musician’s virtuosic talents were certainly not. Impressive though he was, Mozart didn’t create his masterpieces without the sense of hearing. Please welcome Beethoven to the ring.

The German master composer Beethoven lived between 1770 and 1827. As a child, he became a dab hand on the piano, harpsichord, clavichord, organ, violin and viola under the mentorship of his father, Johann van Beethoven and later the court organist Gilles van den Eeden, Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer, violinist Franz Rovantini and concertmaster Franz Anton Ries. In 1780, Beethoven began to learn composition under Christian Gottlob Neefe, who contributed to Beethoven’s first published work in 1783. For a 13-year-old, this was quite a feat.

By his 20s, Beethoven was a well-established performer, composer and concertmaster. However, as he scaled his early adulthood, he began to complain of limited hearing, a crushing prospect for the musically inclined, even more so for those who make sound the centre of their entire being. Over the subsequent two decades, Beethoven’s condition worsened; by his mid-40s, he was totally deaf.

Though his ears, nestled beneath that iconic weave of wavy locks, were completely redundant in his late career, Beethoven miraculously persevered in his musical career. Not long after becoming totally deaf, he wrote his most famous symphony, ‘Symphony No. 9’, otherwise known as ‘The Ninth’. The composer could only imagine what the suite’s most famous movement, ‘Ode to Joy’, sounded like in the concert setting and feel the jubilant vibrations in his frame.

How did Beethoven go deaf?

When we hear that contemporary musicians, especially those from hard rock outfits, have suffered from hearing loss, it is logical to assume that the cause is excessive exposure. Ears exposed, unprotected, to loud music for long periods of time gradually lose their proficiency. The violent vibrations damage the hair cells in the inner ear, thus rendering the organ less sensitive to future sound. Sadly, hearing loss due to exposure to loud sound is mostly irreversible, but rarely does it culminate in total hearing loss.

Loud concerts could have had a drop-in-the-ocean impact on Beethoven’s case of hearing loss, but it certainly wasn’t the primary factor at play. As it happens, historical accounts fail to determine precisely what caused the composer to lose his hearing. However, as his legacy prevailed over the 19th and 20th centuries, researchers and scientists ruminated on the topic relentlessly, reaching several possible conclusions.

In the years following Beethoven’s death, the European medical community became increasingly interested in understanding his health issues, including his deafness. Various cuttings and fragments of remains were reportedly taken from the composer’s corpse over several documented exhumations. During the first exhumation in 1863, researchers took samples of Beethoven’s hair and several pieces of his skull.

The hair and skull samples are dispersed around the world today and have been used in various scientific studies. In the early 20th century, a group of scientists discovered unusually high concentrations of lead in Beethoven’s hair, leading some to speculate that the hearing loss was due to lead poisoning. Other researchers suggest that the composer’s hearing loss was related to a congenital disorder, such as otosclerosis or an autoimmune disease.

Although there is no pathological evidence to determine either way, some suggest that Beethoven’s deafness was caused by an infection. Typhus, lupus, meningitis, and syphilis were not uncommon in the 18th and 19th centuries and, under some circumstances, can all lead to deafness in survivors.

[embedded content]

Related Topics