How did British actor Dan Dewhirst become the face of Venezuelan political propaganda?

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / YouTube Still)

The rise of artificial intelligence has been swift, and it has already divided Hollywood. For studios and tech-driven creators, AI is an exciting new tool that could cut costs by, among other things, generating new scripts, making synthetic background actors, creating visual effects, and using actors’ voices to automatically dub films for foreign audiences.

All of these functions would increase efficiency and money for studios, but for creatives, it’s an existential threat. If a studio can create an AI avatar of an extra or a famous actor and reuse it to their hearts’ content, there would be no need to ever pay a flesh-and-blood actor a salary to work in person. Screenwriters would be out of a job, and VFX artists would be too.

As far off as these risks might seem, the explosion in the AI industry in the past few years has seen exponential increases in what the technology can achieve. Even Oscar-winning movies are using AI technology, including the 2023 ‘Best Picture’ winner Everything Everywhere All at Once. Auteurs from Tim Burton to Hayao Miyazaki have voiced their fears about where the industry’s relationship with the new technology is headed, and one of the key demands of the 2023 actors’ strike that brought Hollywood to a standstill was for protection against AI. They finally came to an agreement, but many actors are less than happy with the terms. Under the new contract, even decreased actors can have their likenesses turned into digital replicas if their estates allow it. Already, the estates of Judy Garland, James Dean, and Sir Laurence Olivier have consented to such agreements.

Even current Hollywood stars are encountering AI versions of themselves that they did not consent to. Earlier this year, Open AI, the company behind the popular large language model ChatGPT, was forced to pull one of the voices used in its latest model due to its uncanny similarities to the voice of Scarlett Johansson. The company had previously approached and been turned down by the actor to create the voice herself.

Famous names aside, there is now an entire industry of companies paying actors for their likenessesses in order to create avatars that can be purchased for broad usage by third parties. These actors may not be top-billed stars, but the upshot of their involvement in these contracts is the stuff of Hollywood melodrama.

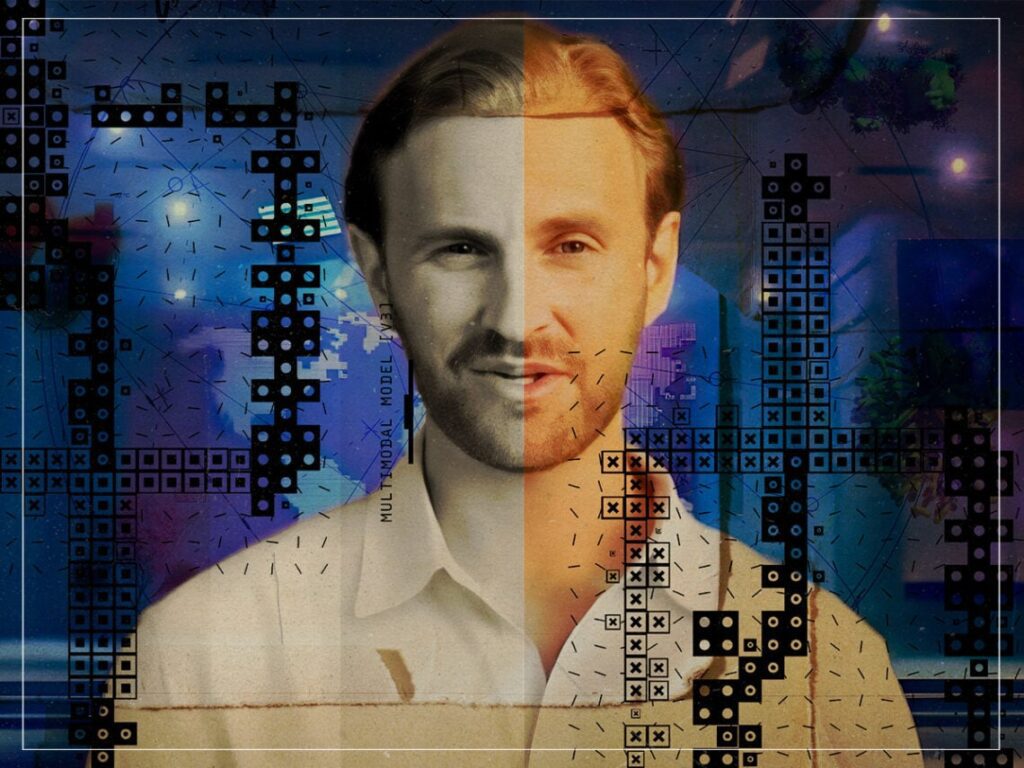

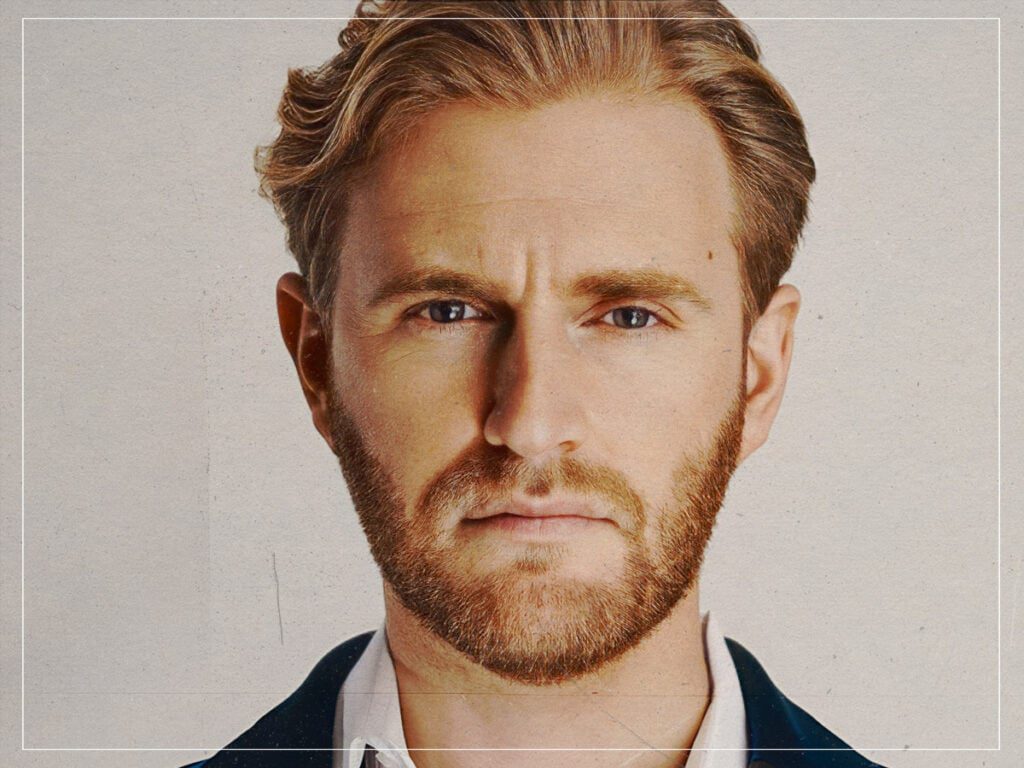

One of the most shockingly audacious cases came to light earlier this year when actor Dan Dewhirst discovered that he had become the face of political propaganda for the government of Venezuela and its internationally condemned president, Nicolás Maduro.

Dewhirst is a British actor who has appeared in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus and Paul McGuigan’s Victor Frankenstein, as well as in ads for brands like Boots and Colegate. In 2021, more than a year before the launch of ChatGPT brought AI to the attention of the wider public, Dewhirst signed a contract with the tech company Synthesia, allowing them to create a digital avatar of him. He became concerned about the scope of the agreement and contacted his agent, his union, and lawyers. When his concerns were raised with Synthesia, the company assured him that his avatar would not be used for illegal or unsavoury purposes.

Two years went by, and Dewhirst was sent a fake CNN report in which his avatar appeared as a news anchor stating false information, including that the Venezuelan government was thriving and that the media had exaggerated its financial struggles.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Dewhirst told Deadline. “My stomach dropped. Everything I was worried about has happened but a thousand times worse. I’m literally the face of fake news.”

Although the video is not as sophisticated as some other deepfaked videos that have come out recently, it does show Dewhirst apparently endorsing a corrupt government that has been charged with human rights abuses.

“I just felt awful,” Dewhirst told The Guardian, “This widely considered dictator in Venezuela had been personally, actually, using my video to spread his propaganda. I mean, you know, it’s horrific.”

In the interview, Dewhirst explained that he had taken the job at the height of the pandemic when work for actors was at a standstill. “I had bills to pay,” he said. “It’s a job. Why not?” Describing his thoughts as he read through the contract, he said, “What is it they would want to book an avatar for that they couldn’t get a real human to say?” He remembered the moment he saw the propaganda video for the first time as an out of body experience. “And then you get that intense set of dread and shame, ‘Oh my god, have I done something absolutely dreadful?’”

Synthesia told Deadline in a statement that the company recognized that content moderation was “an ever-evolving challenge” and that it had fortified its protections against the sort of situations that Dewhirst found himself in. As of yet, however, the UK labour union for actors, Equity, has yet to strike a deal granting protections from AI that are in alignment with the protections of its US counterpart, Actor’s Equity.

[embedded content]

Related Topics