Hear Me Out: ‘Punk’ is a redundant tag now

Posted On

Posted On

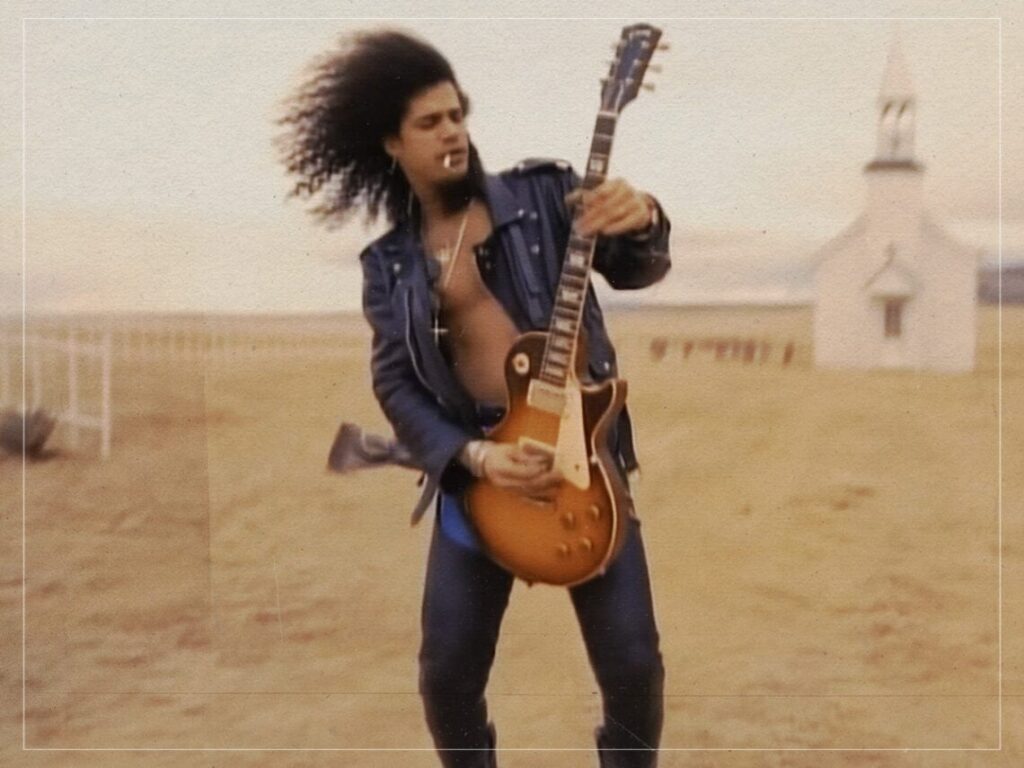

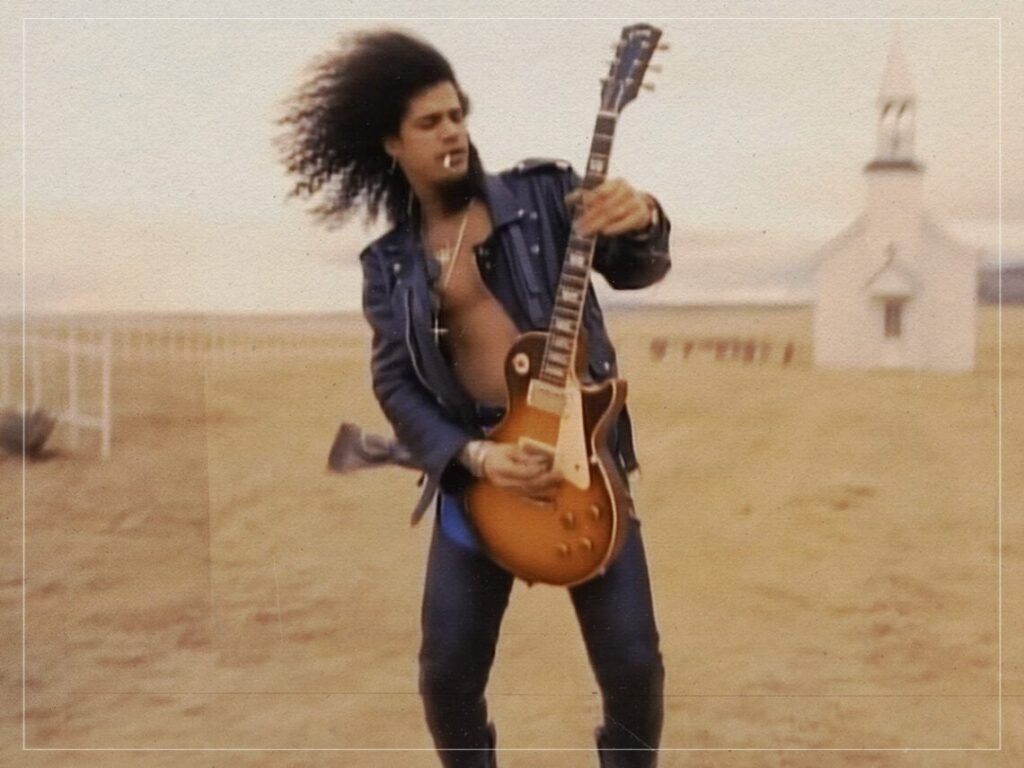

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

There’s no denying that labels and tags are becoming increasingly obsolete in today’s world, especially in music, where standards, genres, and conventions are being transgressed in ways that even pioneering acts like The Beatles and Lou Reed could scarcely have imagined. Artists are now creating fresh contexts, cherrypicking from the vast canon of music history, and crafting art in their own unique image. Yet, despite this trend—where forms once thought separate are being fused into new alloys—one tag that continues to be frequently bandied about is punk. This is curious, as in many ways, it feels like a relic of the past.

When we think of punk, it immediately brings to mind images of the youthful, flame-haired John Lydon, leather jackets, pogoing and amphetamine. But that stereotypical idea of punk is mostly inaccurate. The first wave didn’t last long before it imploded because of its clear pitfalls and was saved by those shrewd enough to initiate post-punk and save the revolution. Since then, the genre has evolved into many offshoots, with the most popular at the minute being hardcore, a multifaceted realm in itself that has the original DIY principles at its core and a generally countercultural spirit.

To understand the common understanding of punk, we have to consider takes from those who were there. The late Ramones drummer Tommy Ramone once offered a substantial point regarding the reactionary motivations of the first wave and what it ultimately wanted to achieve: blowing away the stagnant status quo.

He told Uncut in 2007: “In its initial form, a lot of 1960s stuff was innovative and exciting. Unfortunately, what happens is that people who could not hold a candle to the likes of Hendrix started noodling away. Soon, you had endless solos that went nowhere. By 1973, I knew that what was needed was some pure, stripped down, no bullshit rock ‘n’ roll.”

Extending this general notion, punk in the British sense, which created the stereotypes listed above, was a grittier, more furious rejection of its day’s mainstream rock, the culture it was a product and emblematic of, and sought to do something completely different from what came before, flaunting the standards set by pioneers such as Elvis Presley, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. The Clash even explicitly mentioned this in ‘1977’ from their 1977 self-titled debut. After punk emerged as a concerted cultural force at the 100 Club Punk Special in September 1976, the genre commenced its rapid-fire purge of culture. It wouldn’t take long before the youths were on board.

In terms of rejecting the status quo and embracing a DIY ethic, most hardcore bands align closely with the core values traditionally associated with punk. However, in recent years, many of today’s most celebrated acts in this realm have been rejecting the confines of genre and traditional labels, ushering in a new chapter. Groups like Turnstile, Zulu, and Jesus Piece are pushing boundaries by blending their music with outside influences, creating truly compelling and fresh contexts. This innovative approach is a key reason the genre is experiencing a resurgence, drawing in a wave of new listeners.

It’s not just innovation that renders the one-size-fits-all label of punk redundant today. In Britain, particularly, there’s a tendency—especially among those in the industry, such as PR firms and labels—to describe almost any guitar-driven music with a hint of anger or politics as punk. Yet, broadly speaking—and excluding hardcore outfits—this is rarely the case. While this mislabelling can often be attributed to a lack of understanding, the sloganeering of bands like Idles and a general sense of dismay in a bleak world have contributed to the confusion. Though many of these bands may have clear and agreeable messaging, they’re far from punk in the traditional sense of the term.

While punk was undeniably raw and trashy in its first wave, many of today’s so-called “punk” outfits fall flat, no matter how hard they hide behind the label. Most blatantly recycle ideas from other artists, failing to create music that is remotely innovative or exciting—a stark departure from the original ethos of the genre. Much like what the first wave eventually became, it’s often more about style over substance, talk over action, and an overwhelming waft of pretentious nonsense fanned into the air by clueless imitators.

We need to move past this notion of a homogenised description of punk. It’s hampering progress, if anything. Ironically, since the early days, punk has been a mostly redundant tag anyway, with there clear philosophical agreements between the Utopian, deeply artistic vision of Crass and the nihilistic perception of those who followed what the Sex Pistols started. Moreover, John Lydon rejected the tag while still in the ‘Anarchy in the UK’ band and quit them to found his own conduit for expression, Public Image Ltd, who unburdened themselves from pigeonholing and viewed punk as nothing more than “fascist”.

[embedded content]

Related Topics