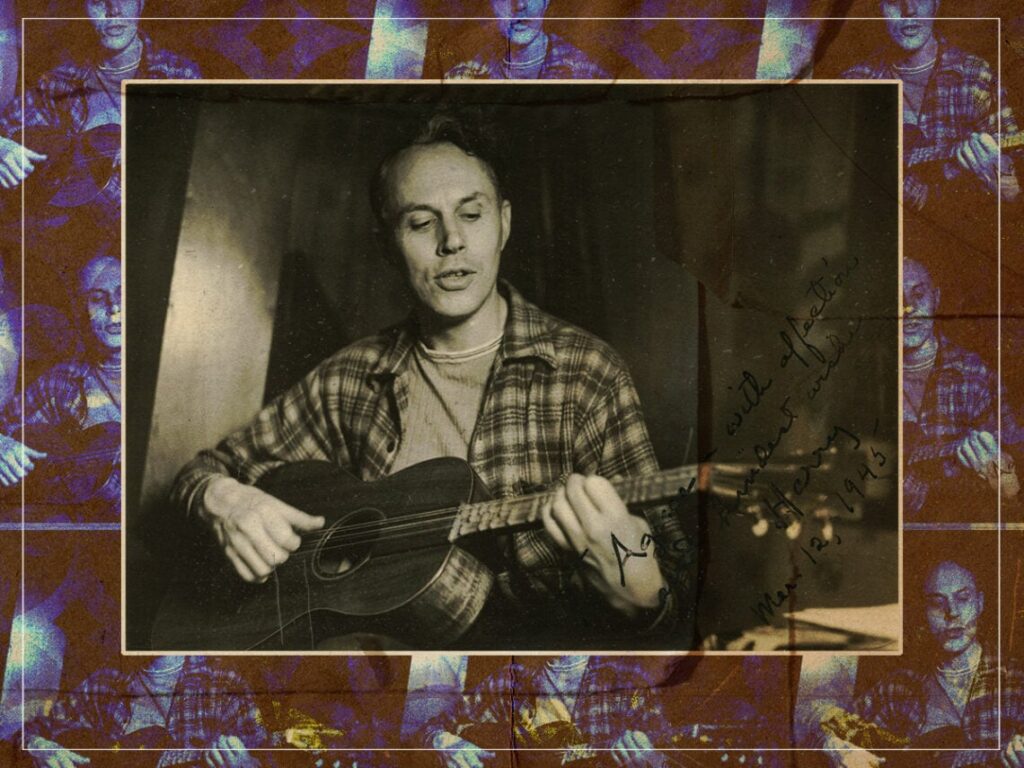

Harry Partch: the maestro of microtonal music

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Bandcamp)

Across the modern history of music, few figures have dared to challenge the conventions of the art form. Although many of these pioneering characters were shunned or rejected during their time, their work often went on to have an infallible effect on the lineage of music, even if the artists themselves have long since been forgotten. Such is the case with American composer and theorist Harry Partch, who dedicated his existence to breaking down the boundaries of traditional composition through microtonal scales.

Born in 1901, Partch could read music from an impressively young age, spurred on by the support of his mother. During his adolescence, the budding California composer took particular interest in the violin, piano, mandolin, and even the reed organ.

This dedication to music soon took Partch to the doors of the University of Southern California’s School of Music. After two years at music school, Partch grew annoyed with the quality of teachers there; in 1922, he dropped out of the school to pursue his own musical desires.

Only a year after his departure from music school, Partch completely rejected the conventions of traditional European composition, and he would later burn all his previous compositions as a statement against the conventional tuning used by European composers. This was the beginning of Partch’s interest in microtonal music, which would go on to define his music career.

The vast majority of modern music, at least in the Western world, uses a standard tuning known as 12-ET, or 12 equal temperament. Essentially, this means that the octave is divided into 12 equal parts on a scale. The system is fairly complex, involving all sorts of mathematical equations and musical theories that are far too complicated to get into outside of a university lecture hall. However, the main thing to note is that this 12-ET system dominates Western music and has done so for centuries.

This idea troubled Partch, who pursued an alternative tuning known as microtonal music, which splits the octave but not into 12 equal tones. Achieving such a feat was a fairly daunting task, particularly for somebody barely in their 20s at the time. To achieve the microtonal music he so desired, Partch began constructing his own unique instruments, such as a viola that featured the fingerboard of a cello.

Partch worked tirelessly to research and experiment with microtonal music, employing a variety of other musicians and instrument-makers in the process. His work took him around the world, particularly to Europe where he met pivotal figures like Kathleen Schlesinger, who curated ancient musical instruments for the British Museum.

Upon returning to the United States in 1935, Partch found himself homeless for a brief period of time at the height of the Great Depression. Still, he continued to research this defiant musical theory in the face of extreme adversity.

Eventually, his work paid off. After performing a set of compositions by the name of Americana at Carnegie Hall in New York City, the composer began to receive support from organisations like the Guggenheim. Then, two decades after dropping out of university himself, Partch began to teach music at The University of Wisconsin. For the next few decades, Partch would espouse the joys of microtonal music to universities across the United States, causing many young students to challenge the conventions of modern music in the process.

For much of his life, Partch relied on academic grants and financial support to get his compositions out there, and he was certainly successful in his aims. Continuing to compose into his old age, the musical rebel completely altered the norms of classical music and composition. His work continues to be hugely influential on the world of experimental music and the avant-garde to this day, 50 years on from Partch’s death in 1974.

[embedded content]

Related Topics