Cinéma du Look: the lesser-known 1980s French cinematic revolution

Posted On

Posted On

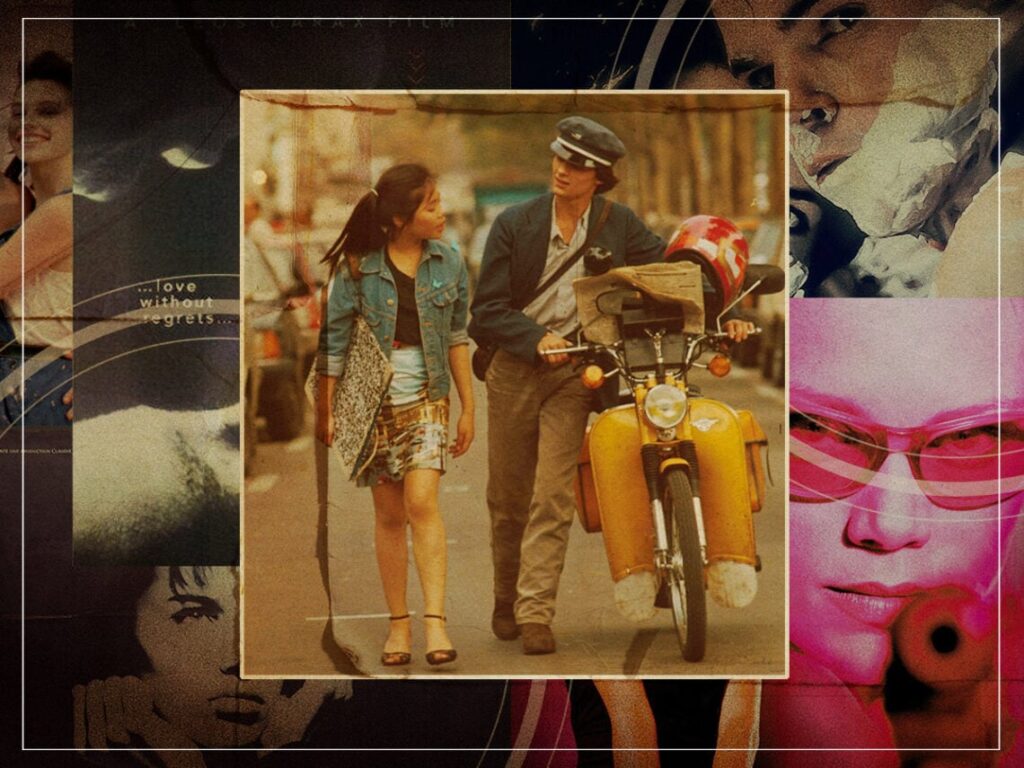

(Credits: Far Out / MUBI / Original Promo / Criterion Collection / Compagnie Commerciale Française)

Any discussion about French cinematic revolutions will inevitably draw attention to the pioneers of the nouvelle vague who completely turned the medium on its head. From Jean-Luc Godard‘s incisive reconfigurations of cinema’s visual language to François Truffaut’s whimsical experimentations with genres, the French New Wave not only had an impact on national cinematic forms but also inspired global trends.

However, the development of the cinematic language in every country undergoes distinct periods of evolution that are characterised by specific visual frameworks and techniques. The nouvelle vague started a conversation that not only pulled in filmmakers from all around the world but also within the homeland as well, creating an artistic response to the New Wave.

Termed the “Cinéma du Look” by critic Raphaël Bassan, the movement garnered momentum in the 1980s as a select group of filmmakers decided to create a new kind of cinematic tradition that sought to break free from the seemingly inescapable shadow of the New Wave. These included major figures like Leos Carax and Luc Besson, who made their movies with a particular artistic objective in mind.

While the New Wave auteurs were also concerned with the grammar of cinema and how it influenced the aesthetic foundations of a rapidly changing medium, the Cinéma du Look period saw a rise in stylish and slick spectacles that weren’t really overtly interested in narrative storytelling. Instead, they wanted the images to speak for themselves, directing the audience to the fundamental phenomenon associated with cinema: voyeurism.

Choosing to highlight cinematic subjects that were not too conventional at that period of time but are very popular now, directors like Leos Carax featured the alienated youth at the centre of their works, using their paradoxical combination of cynicism and hope to build a unique artistic thesis for a shifting modernity. The result is enigmatic gems such as Boy Meets Girl, where the element of romance is viewed through lenses of image-building and ideological complexities rather than the frameworks of traditional love stories.

Through these striking collections of imagery and visual stylisations, the filmmakers explored the sociological conditions of contemporary youth while also launching fervent political protests against the establishment. Besson’s Nikita and Carax’s Mauvais Sang remain prime examples of this phenomenon, forming a central part of the political legacy of the Cinéma du Look that is far less discussed than its visual contributions.

One pioneer of the movement who didn’t receive the same amount of attention as some of his contemporaries, maybe because he became completely tied to the Cinéma du Look era while others moved on, was Jean-Jacques Beineix. Probably the epitome of what the movement stood for, his 1981 gem Diva laid down the framework for everyone else in more ways than one, being cited by many as the first French postmodern film.

Beineix’s Betty Blue also garnered widespread acclaim, but interest in the French auteur’s later projects steadily declined. He later said in an interview: “Betty Blue and Diva were huge successes, and distributors should figure out that audiences may be interested in watching the other films… If I understood it, I would give you an explanation about the dysfunction in this business. But the price of talking too much is very high. In the background, they stab you for being an outlaw.”

Maybe Cinéma du Look was just a moment in time within the context of French cinema instead of a coherent artistic march towards a new form of filmmaking. Even then, it’s a period that is indispensable if modern audiences want to understand the lineage of some of the spectacle-focused and visually stylised works that flood the market today.

[embedded content]

Related Topics