Bob Dylan’s 25 greatest songs of all time

Posted On

Posted On

‘Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues’

Once titled ‘Just Like Juarez’, Dylan would use his 1965 track ‘Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues’ as an homage to some of his literary heroes.

He makes mention of Edgar Allan Poe, one of America’s greatest storytellers, Tom Thumb himself who derives from Enlish folklore and Jack Kerouac, the iconic Beat writer who many would argue laid foundations for artists like Dylan to build upon. Soon enough, Dylan would become a literary icon in his own right as tracks like this unfurled for millions.

[embedded content]

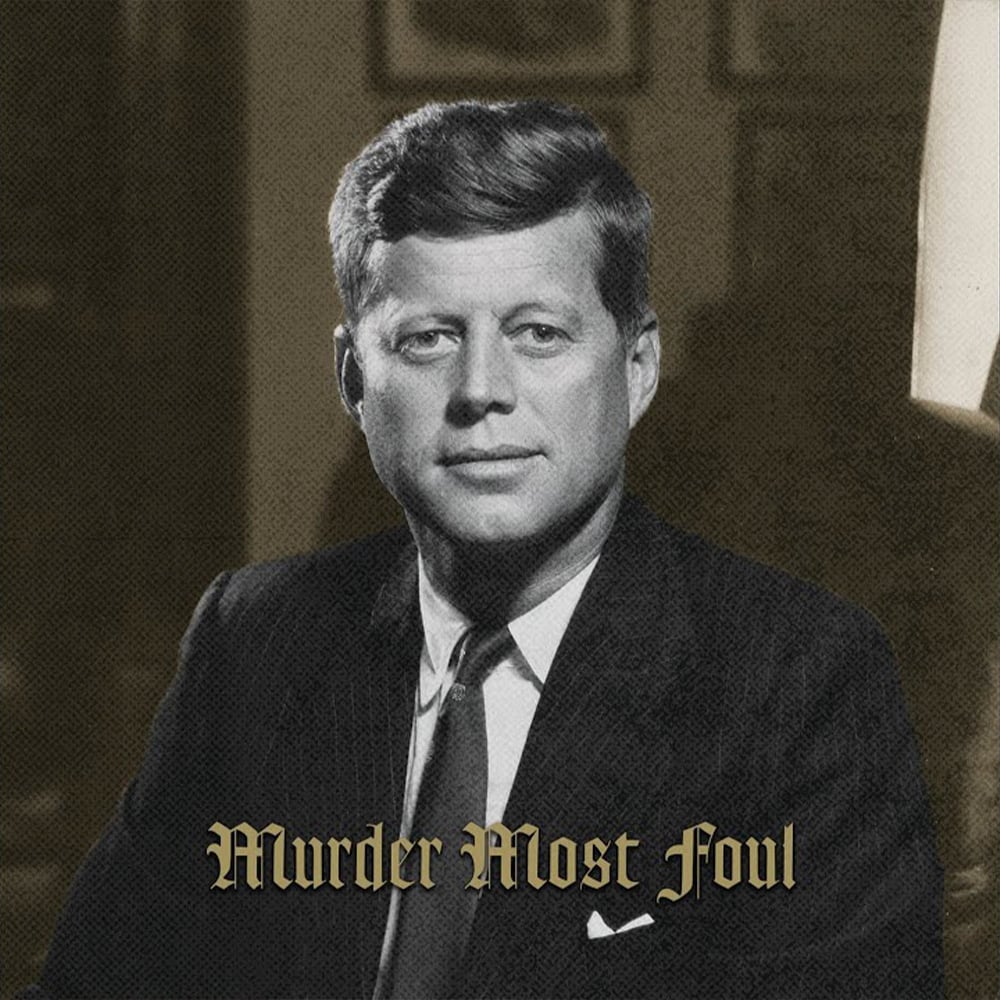

‘Murder Most Foul’

Whether it has been protestors picketing his property and calling for him to join them in direct action, critical lambasting’s of his born-again Christian phase or playing through pain as his hand recovered from a motorbike accident, it is clear that Bob has braved hardships in his career and his noble battle through them is proof that he did it all for the love of music.

In 2020, as he approached his 80th year, he turned in yet another masterpiece. ‘Murder Most Foul’ was an embodiment of his entire career, from his profound sense of place within society, to the simple deliverance of music, and lastly his absolute love of the art. The seminal last line to this song – “Play, “The Blood-stained Banner” play, “Murder Most Foul.” – contains all his wit and daring to deliver a career-long message of hope and comfort in creativity.

[embedded content]

‘Sign on the Window’

Perhaps ‘Sign on the Window’ is an inclusion that may raise some eyebrows, and perhaps I’ll Google will toss this old article back to me, and I’ll second-guess the inclusion. However, one of the most beautiful things music can do is transfigure itself to a higher level even after a myriad of listens.

Within the depths of lockdown, this track moseyed up and warmly declared itself to me as one of the most underrated in Dylan’s back catalogue, and I wholeheartedly agreed. The song shines a light on the duality of the turmoil Dylan was facing at the time of writing it: the company that came with fame was bad, but the loneliness of self-imposed solitude was worse. Though on the surface this a very specific notion, in a spiritual sense, loneliness versus the fear of taking the first steps against it is a battle that resonates with a far greater universality.

[embedded content]

‘The Man In Me’

After a decade of musical dominance in the 1960s, Dylan found himself retreating from the accursed ‘voice of a generation’ tag that was bestowed upon him. For his 1970 album, New Morning, he intentionally stripped his songs of anything that could be interpreted as some sort of satirical metaphor, and surprisingly, such constraints resulted in somewhat of a masterpiece.

‘The Man in Me’ stands out in the party of Dylan’s back catalogue as a chilled-out presence sipping on a White Russian. If the song was any more laidback, he’d have to play it lying down and he invites you along to bask in this sonic balm. It is a dreamy piece of music, ideal for bathtub escapism (just make sure there aren’t any marmots about).

[embedded content]

‘She Belongs To Me’

There’s a beauty attached t any song that can gneuinely pitch itself as ironic and yet still feel emotionally reverent, and ‘She Belongs To Me’ is one of them. Dylan’s title might be one of possession, but the woman he’s singinabout is fiercely independent and leaves him in awe.

It has ofte been suggested by Velvet Underground’s John Cale that Dylan wrote the song about powerhouse supermodel Nico. Joan Baexz and Caroline Coon have also been suspected subjects in the track, but the most important thing is balance between sweetness and greatness Dylan bestowes upon this semi-mythical figure.

[embedded content]

‘Girl From The North Country’

It might seem strange to pick what is one of Dylan’s more controversial songs as his best, but truly, that is what makes him such a superb songwriter. This track’s controversy centres on a line he borrowed from ‘Scarborough Fair’, as he sings “Remember me to one who lives there/She once was a true love of mine”.

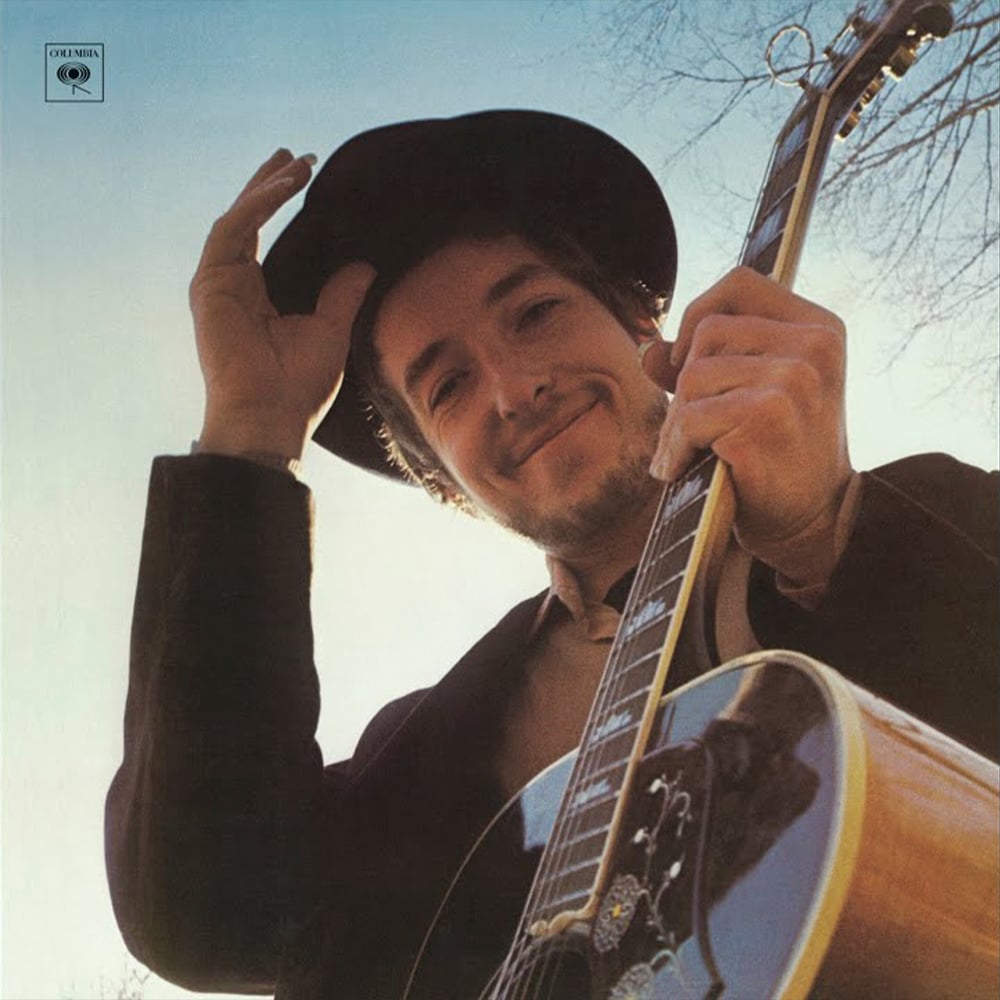

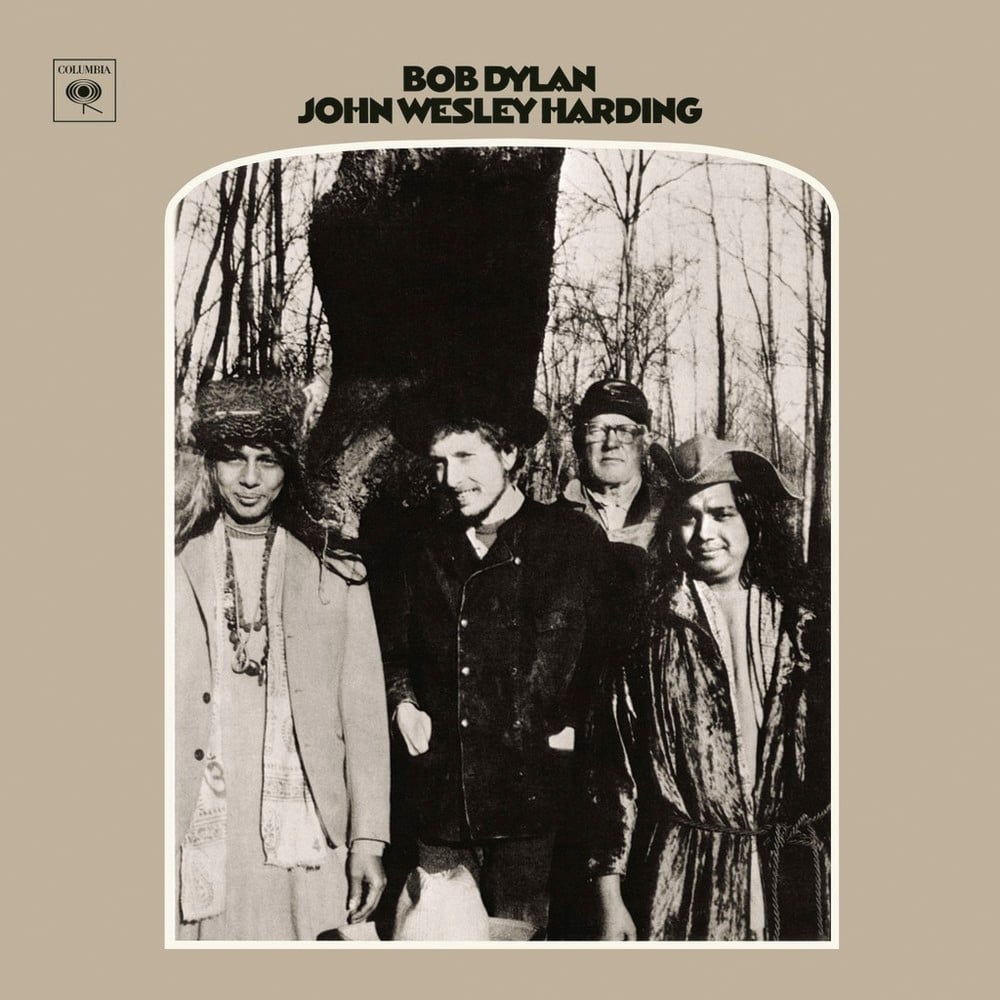

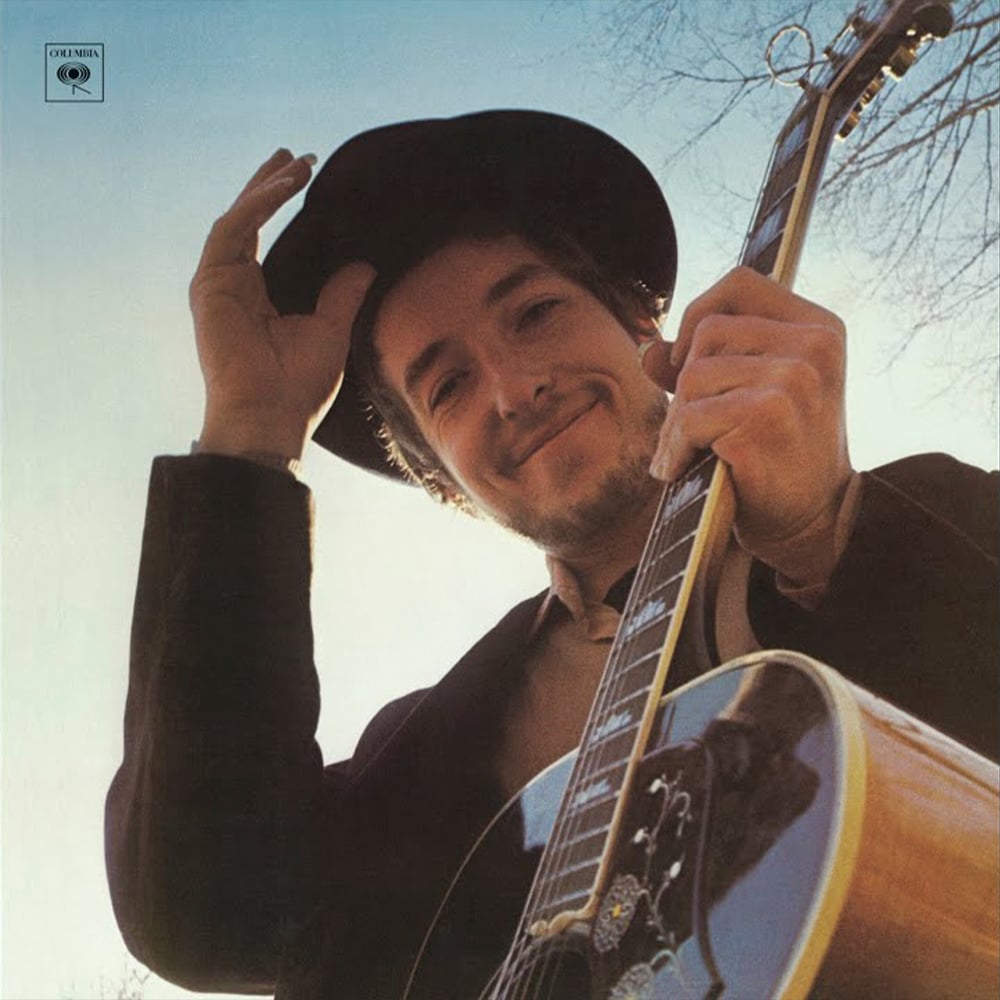

However, outside of that, Dylan’s track is unique and powerful in every sense. Heartfelt and homey, Dylan is able to traverse the necessity for universal appeal and make songs that felt like warm bowls of soup. It brought a sense of America to a nation that was tearing itself apart when it was first written and found a new home alongside Johnny Cash in Nashville Skyline.

[embedded content]

‘Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands’

Written about Sara Lownds, Dylan’s wife of the time, this is undoubtedly one of Dylan’s most masterful songs. Descriptive and delicate, the track unfurled in an eight-hour session that seemed like it would go on forever. Dylan once said, “It started out as just a little thing, but I got carried away somewhere along the line.”

At 11 minutes in length, it is one of those tracks that confirms that Dylan’s mind was like nobody else’s. No other artist would dare to write such a tune, and few could actually keep the attention of its listeners during the runtime. But with every note a story grows, and we are hanging on, waiting for more.

[embedded content]

‘Tangled Up In Blue’

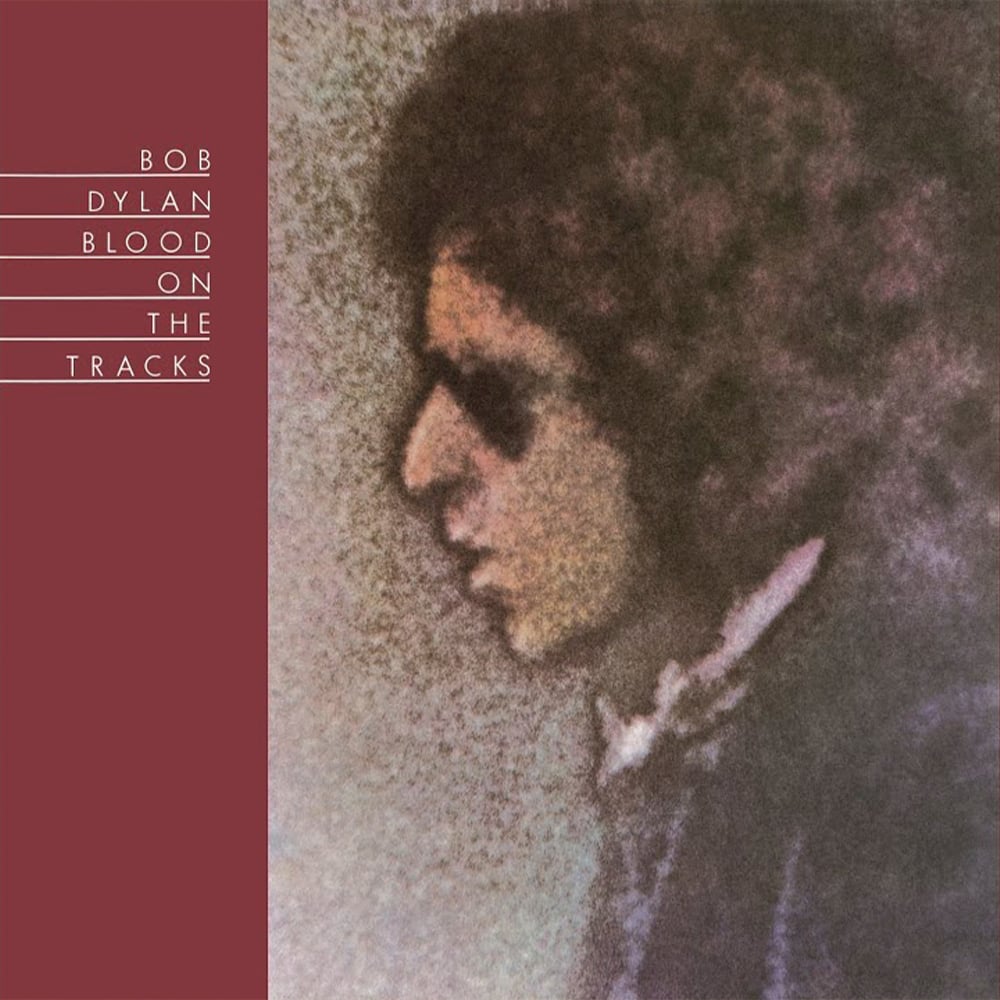

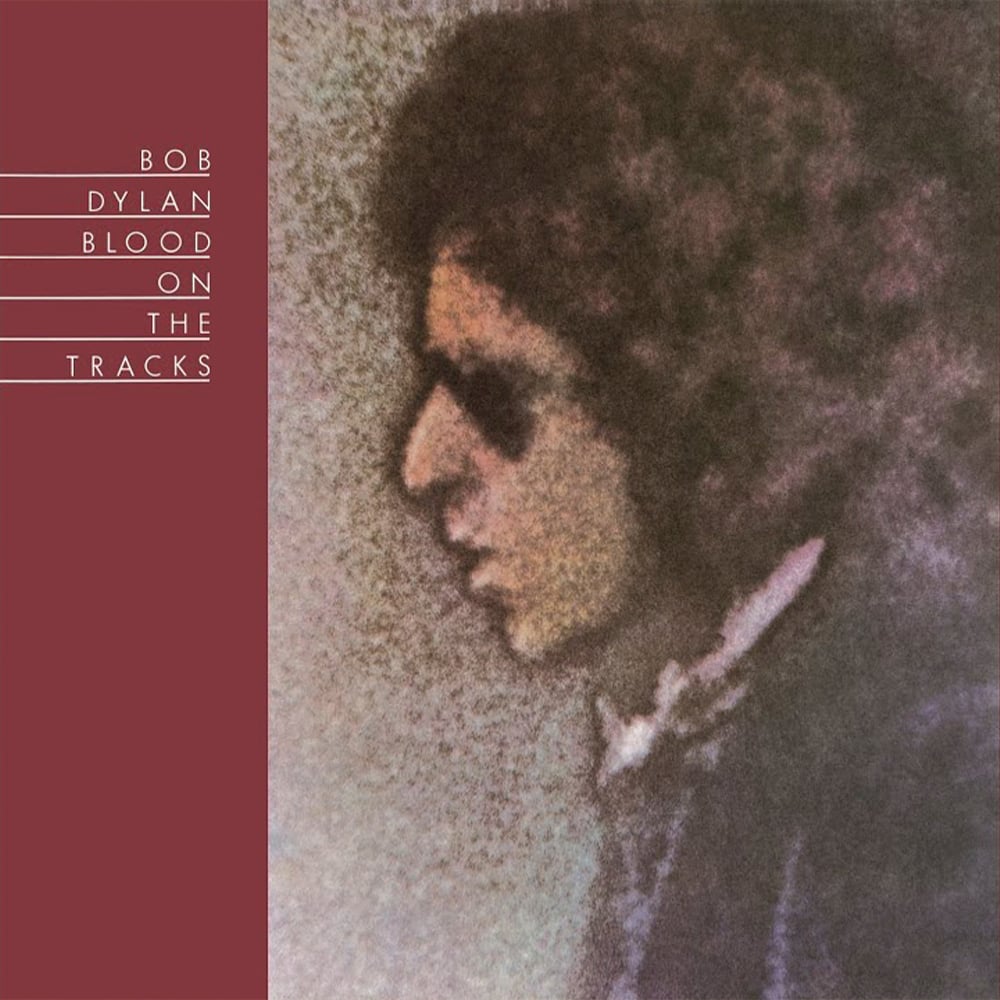

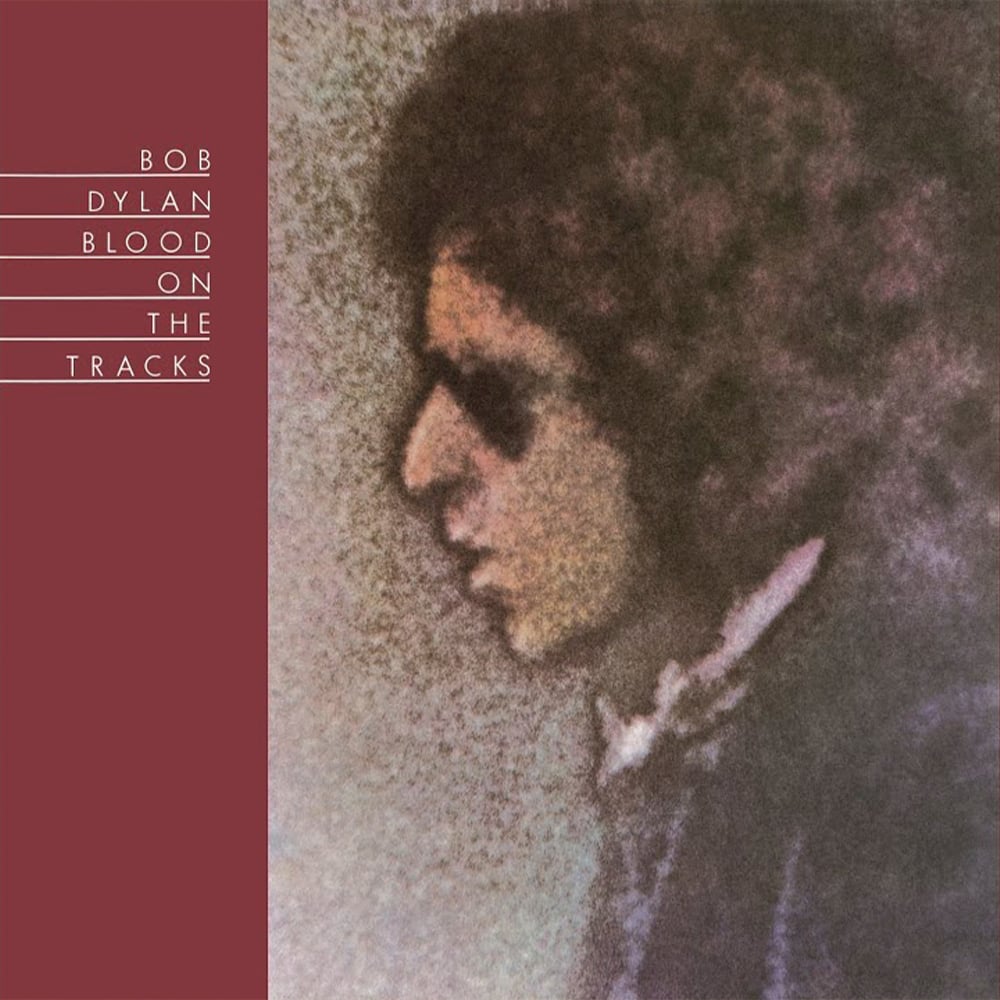

A part of arguably Dylan’s greatest album, Blood on the Tracks, ‘Tangled Up In Blue’ represents one of Dylan’s most enterprising moments, all the while maintaining his notorious drawl. Though the singer had always been open about his feelings, allowing his music to do most of the diarising needed to succeed in the pop world, this track is one of his most open.

Not because it accurately depicts the ending of a doomed relationship, though it does that with the sweetest efficiency, but because he portrays them in a veracious and voicefrous way — through fragmented vignettes. The kind that usually only arrives after the event, but for Dylan’s artistic eye, appeared within a moment’s notice. It provides grounding to one of the singer’s finest efforts.

[embedded content]

‘All Along The Watchtower’

The deep, introspective spiritualism of Dylan’s oeuvre is often shadowed in biblical overtones. They are many ways to interpret this song, but if my opinion is worth a dime, it seems to be about Christ upon the cross and the two thieves conversing on either side. I could be wrong, but it proves an important point regardless: it is the ambiguity and philosophical scope of such songs that make them stand out as masterpieces in the world of modern music.

With ‘All Along the Watchtower,’ he provided a message that usurped spiritual vapidness and despondent nihilism that pervaded an era of despair in America. In favour, he presented a note of fullness and forgiveness through an attitude of hope and the joyous sequestering of cynicism that comes from looking for solace beyond the despairing, insular world of the watchtower.

[embedded content]

‘Shelter From The Storm’

Now the movie business is a generally vacuous industry, but it knows good music, and ‘Shelter From The Storm’ is one of the most used songs of Dylan’s arsenal when it comes ot movies. One such famous moment comes in St Vincent, where Bill Murray gives a truly mesmeric performance of the track.

The reason he is able to do that is that it is one of Dylan’s simplest tunes. Not only is it made up of three chords and played very comfortably, but thematically, the ideas are as universal as he has ever produced. A lover providing refuge for a bedraggled life-traveller. It’s an image everyone can connect with.

[embedded content]

‘Idiot Wind’

With Blood on the Tracks, Dylan was back to narrative songwriting with a bang. The songs were more so stories regaled rather than predicaments dissected, and ‘Idiot Wind’ is a ferocious tale of rock ‘n’ roll.

The song is spewed out bile, which proves that, for all his wonderful, sweet touches and poignancy, he’s often at his best when his pen is moved by rage. There are couplets with humour and mirthful scorn akin to the pithiness of the eponymous punk poet John Cooper Clarke. It’s a brutal tirade that any rapper who be happy to host on a diss track, all housed in a rolling earworm of a melody to boot.

[embedded content]

‘Lay, Lady, Lay’

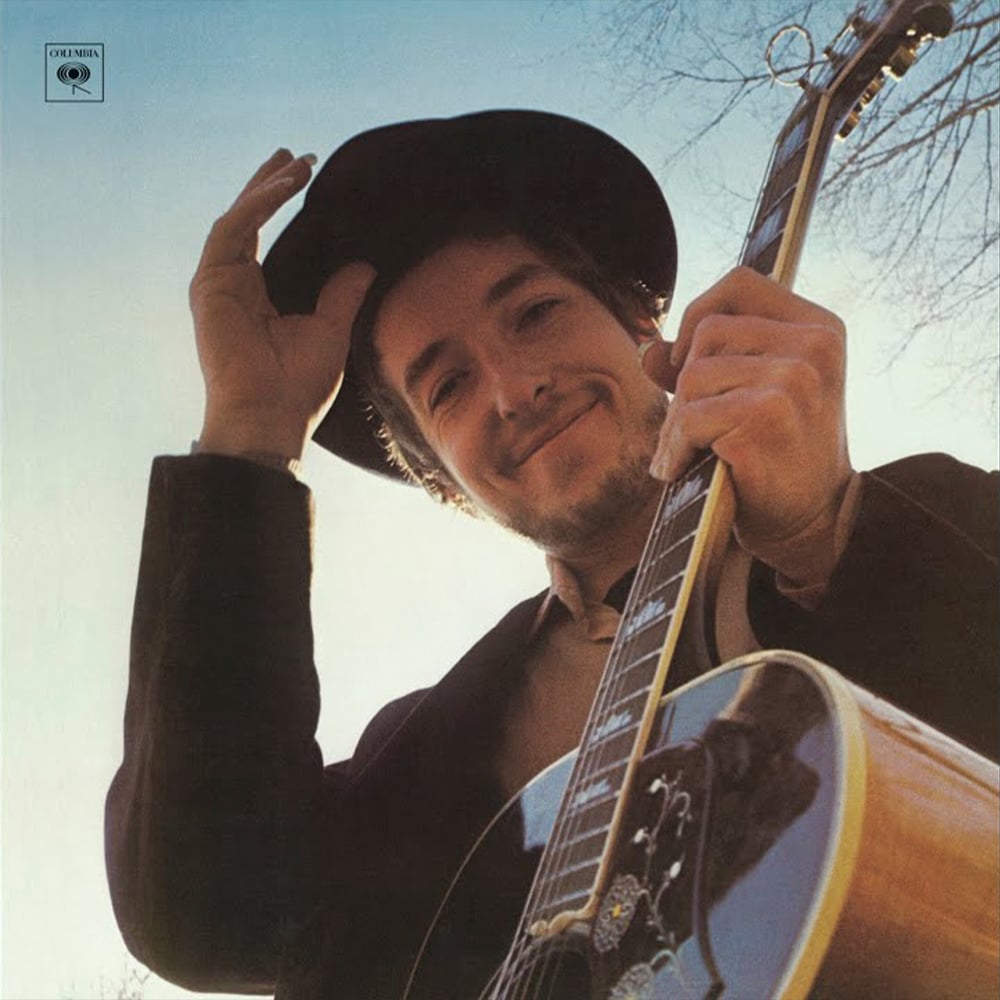

Nashville Skyline, the album that features the incredible track ‘Lay, Lady, Lay,’ was a huge departure for Dylan. True, he had ditched folk a long time ago, but now it seemed he was also ditching the voice of a generation, too. The singer puts on his best croon to bring the album to life, and there is perhaps no better showing of this than on ‘Lay, Lady, Lay’.

Detractors may call this song out for being a little on the cheesy side. After all, what’s rock and roll about pledging to be a dutiful husband? But, in a catalogue of songs that preached about the absurd beauty of love and the heroic nature of war among countless other themes, it feels fitting that at least one of his songs should be about devotion.

[embedded content]

‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’

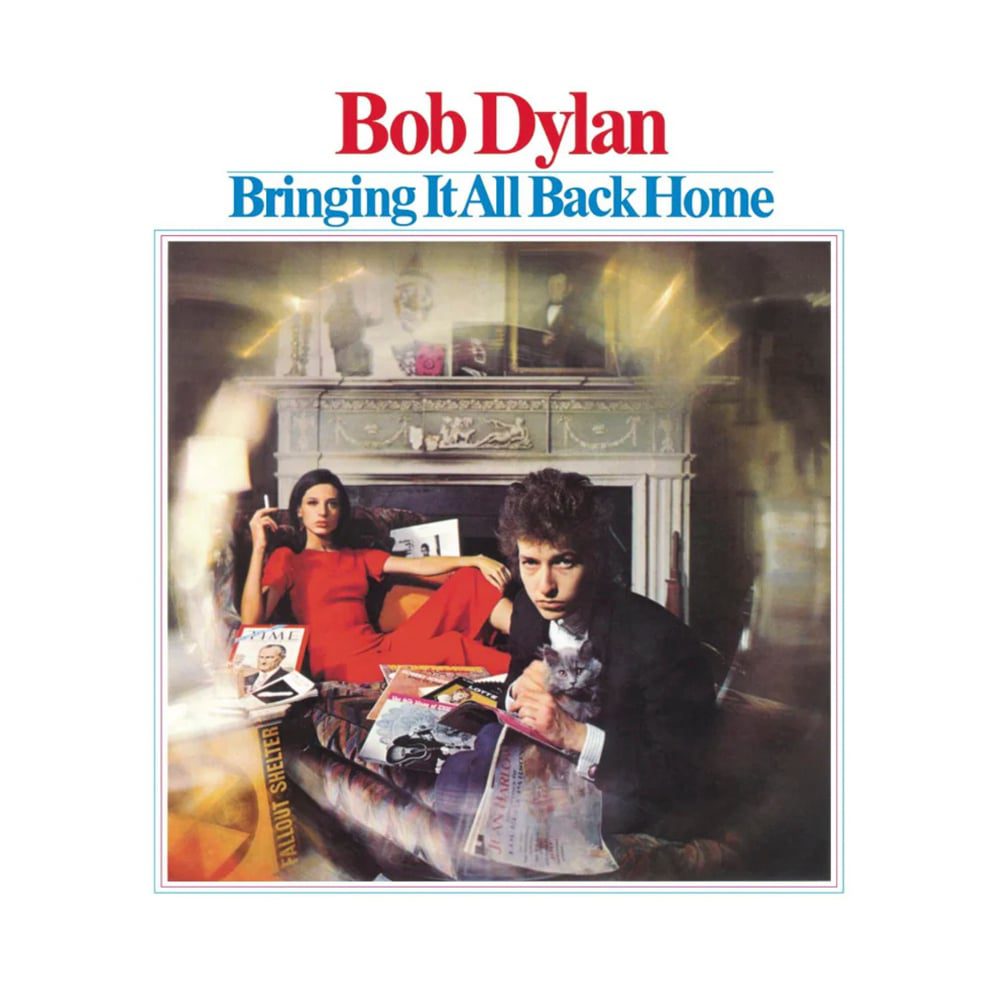

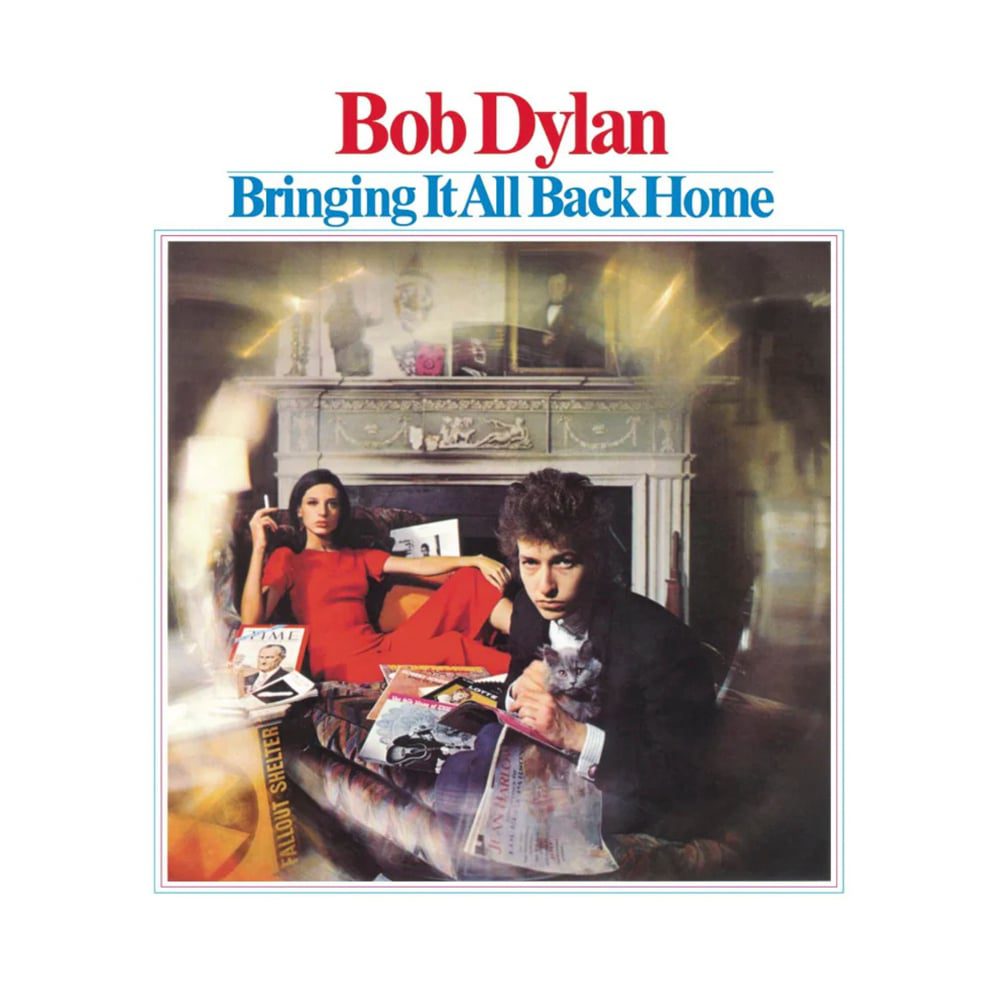

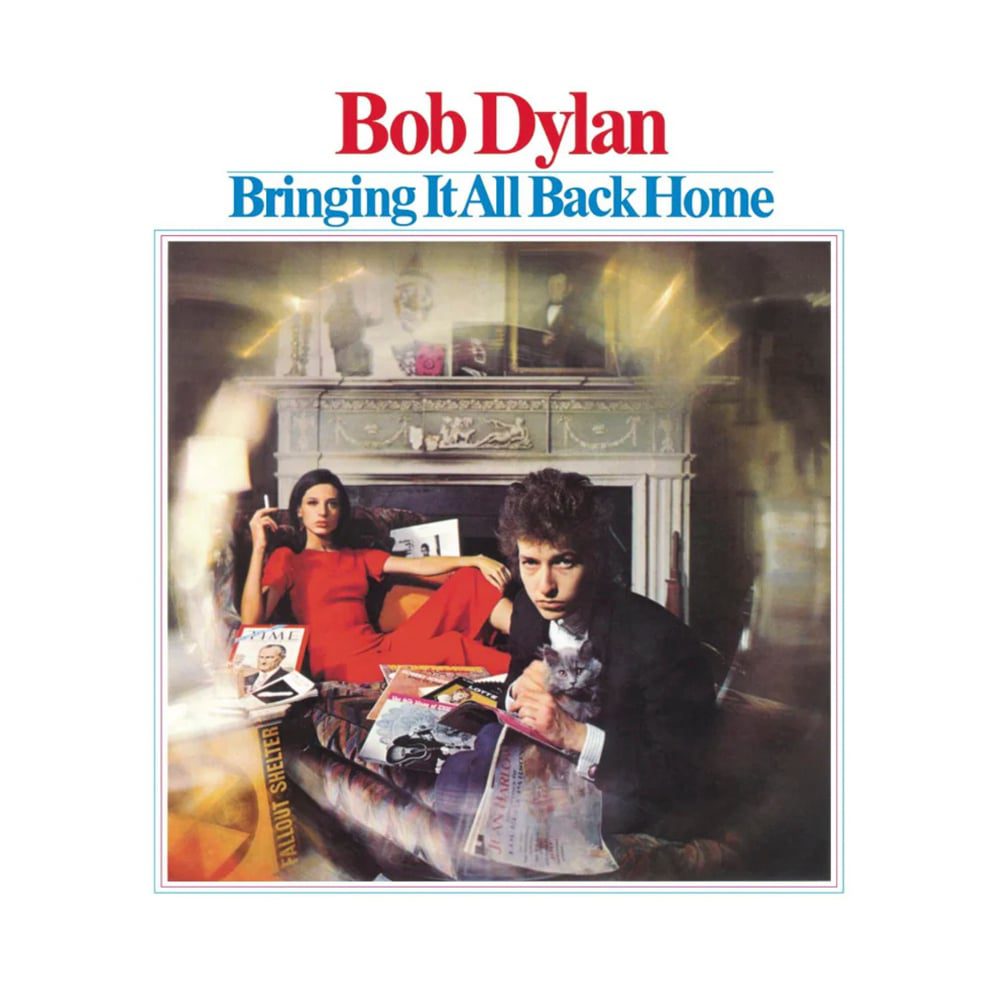

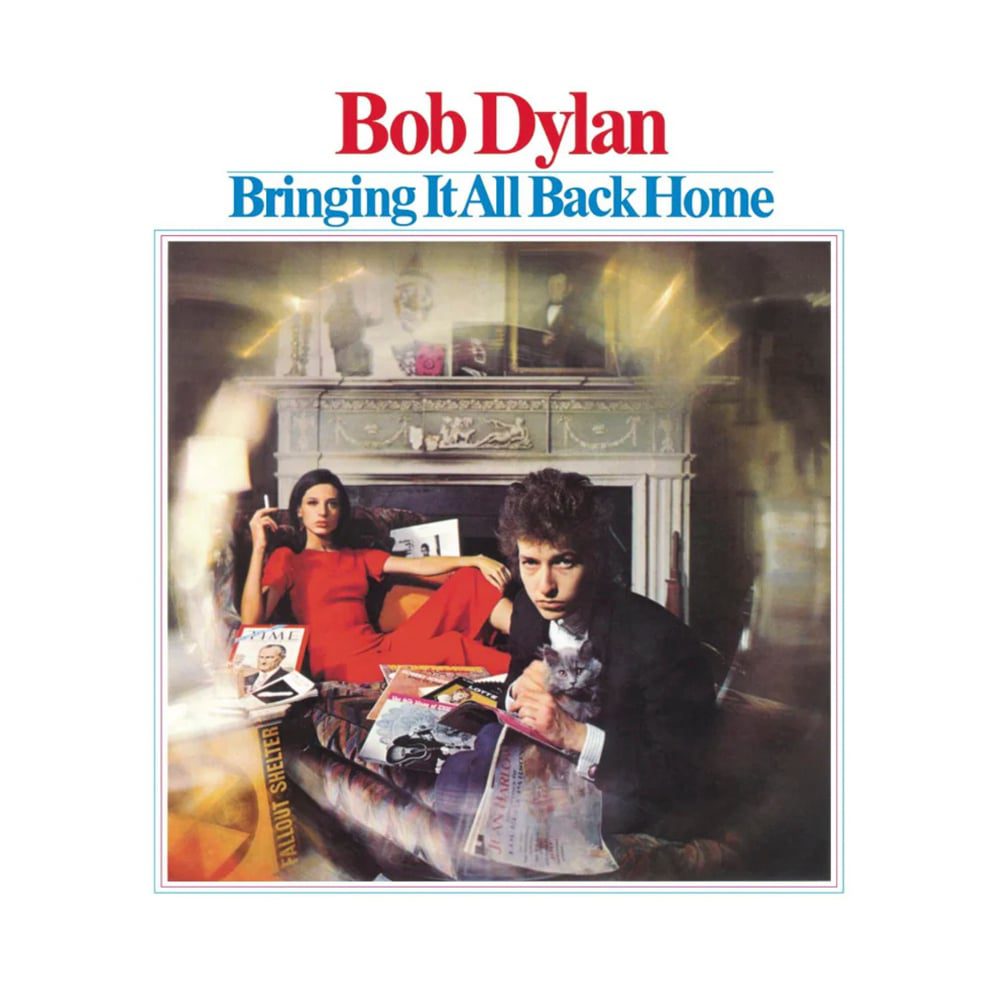

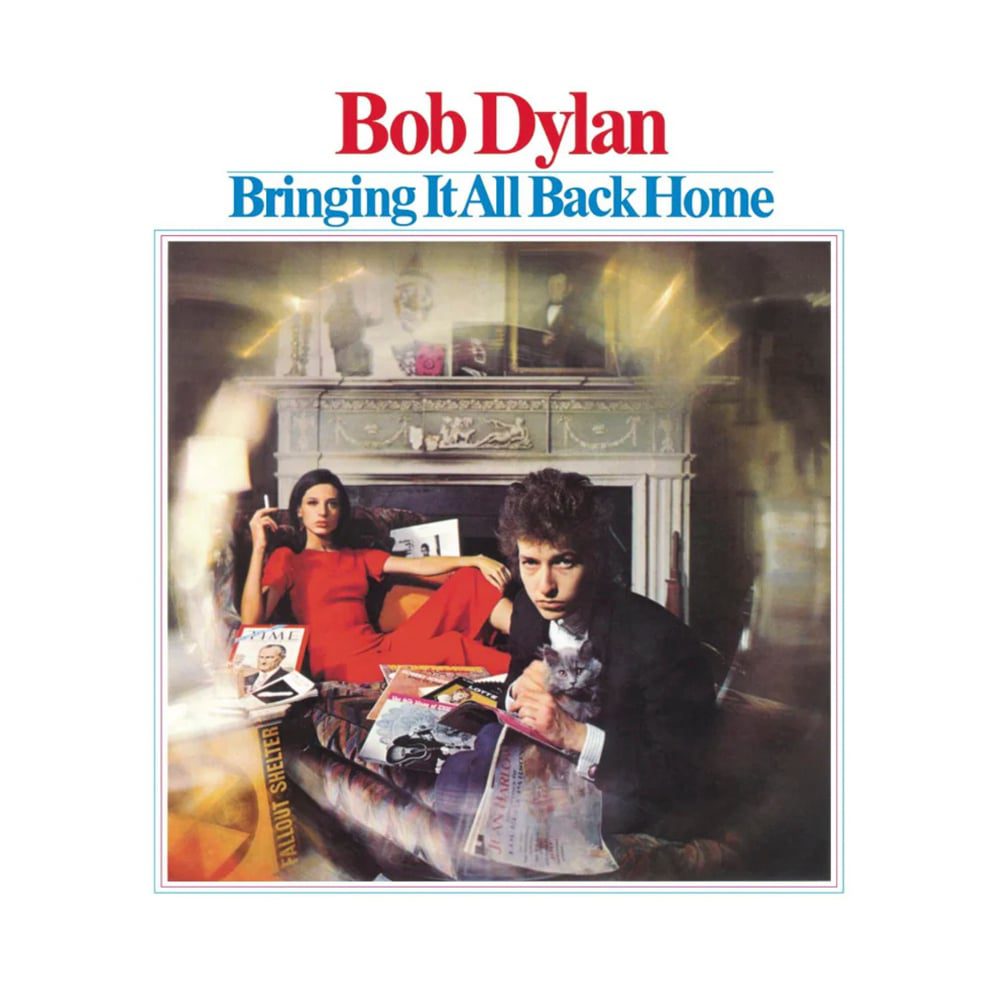

1965’s Bringing It All Back Home is one album that few musicians worth their salt would disagree over. Positively packed with reminders of Dylan’s unfathomable and unfiltered talent, ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’ has gone on to typify this moment of artistic purity for Dylan. It’s another track that puts Dylan in the centre of a pool of petrol, only to sing: “Strike another match, go start anew”.

In typical Dylan fashion, we are unsure whether he was directing his self-help memos of moving to a burned lover or indeed the fans who were still vying for his folkie blood. The truth is, like all great Dylan songs, it really doesn’t matter. Lyrically robust without feeling flagrantly indulgent, the song remains a cherished piece of his unwavering canon.

[embedded content]

‘I Threw It All Away’

In an era that found Dylan crooning with a silky voice that seemed to have power blasted off the old “sand and glue”, he crafted a song suitably sweet to go along with it. However, it was also such an unadorned dose of unarguable profundity that it was sweet, but never saccharine, like spiritual honey.

Although the melody may be dainty, the message is anything but: in an almost daringly simple way, Dylan croons out “Love and only love,” in a bold entreaty of harmony. This defiant mantra emboldens the melody with a monolithic sense of spiritualism. Nick Cave said if he could have written any song, it would be this, and that’s a good enough calling card to earn its place on any list.

[embedded content]

‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’

To open his electric oeuvre on Bring It All Back Home Dylan met his “Judas!” picketers with a fist. Rather than clutch to the safety of a successful formula, Dylan laced this proto-rap song with a flourish of jostling acoustic and electric guitars.

The song is a visceral bludgeon and an incendiary attack on orthodoxy in all its guises. However, what really makes it a masterpiece is that it thrashes about like a mule, kicks the naysayers into touch, and makes them look like Amish arbiters of music in two minutes and twenty-one seconds flat. It has one of the greatest music videos of all time as an added extra, just to ram home that Dylan was rattling culture about like a floating butterfly and a stinging bumblebee in this period.

[embedded content]

‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’

The saying goes, “hell hath no fury like a woman scorned,” but perhaps they have never witnessed Bob Dylan penning a song about the ensuing Cuban Missile Crisis. An onlooker who was there when the songwriter began working away at the fantastic ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ said the song, “roared right out the typewriter”.

Full to the brim with apocalyptic imagery and the kind of lyricism that only Dylan could muster, the song was recorded in one take and hasn’t spent much time out of the studio since. Covered endlessly, the song remains a vibrant piece of anyone’s set, let alone the man who spawned it.

[embedded content]

‘It’s Alright Ma, (I’m Only Bleeding)’

Few songs announce Bob Dylan as quite possibly the most gifted lyricist of all time more succinctly than ‘It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding’. Containing one of Dylan’s most prophetic and poetic lines: “He not busy being born is busy dying”, the song ranks as one of the greatest on this alone.

When you add into the mix the body-shaking vitriol of the rest of the song and you have a heady cocktail capable of rendering an elephant unconscious. The basic premise of the song is not to trust your establishment, something that Dylan maintains to this day. It was this sentiment that made the songwriter one of the most widely accredited around.

[embedded content]

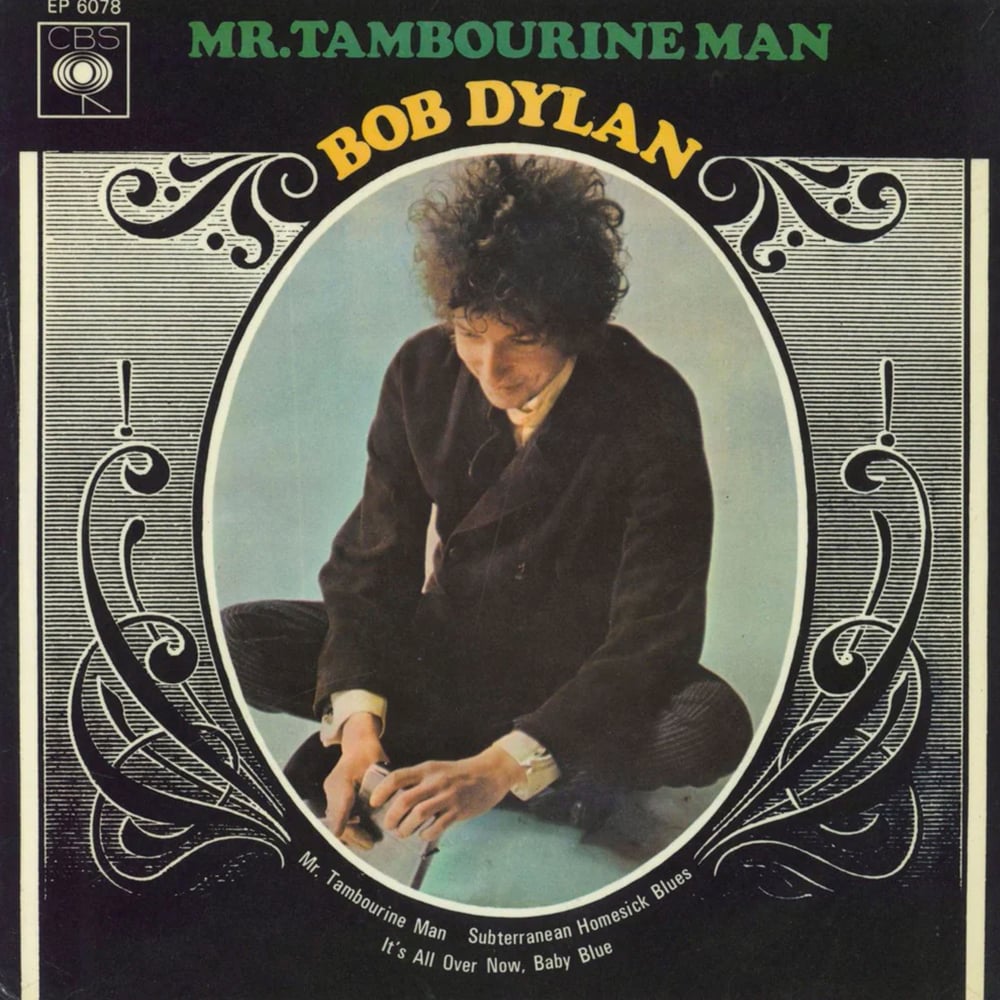

‘Mr Tambourine Man’

Of course, no list would be complete without one of Dylan’s most famous songs, ‘Mr Tambourine Man’. Though it would take The Byrds in the 1960s and Michelle Pfeiffer in Dangerous Minds in the nineties, to bring the track the acclaim it deserves, the only aficionados complaining about the song’s inclusion in our list are bona fide snobs. The song, assessed separately from Dylan’s mystique, stands up to anything else released in the decade.

Wrongly pinned down as a “drug” song by many, the track is more accurately seen as a moment of reflection of writing itself. Built out of moving imagery and non-contextual vignettes, the track does carry similar nuances to the actual feeling of being a little spaced out, but that’s the exact same effect as the best poetry has too.

[embedded content]

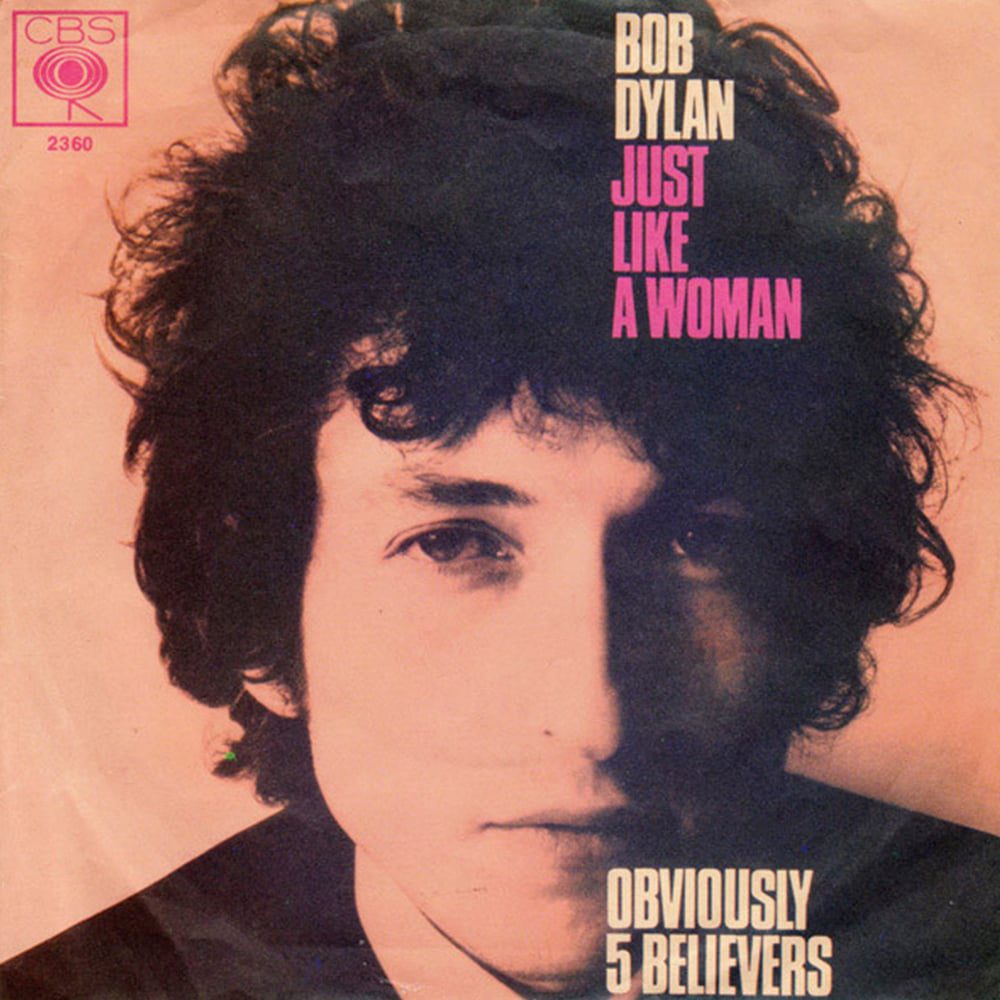

‘Just Like A Woman’

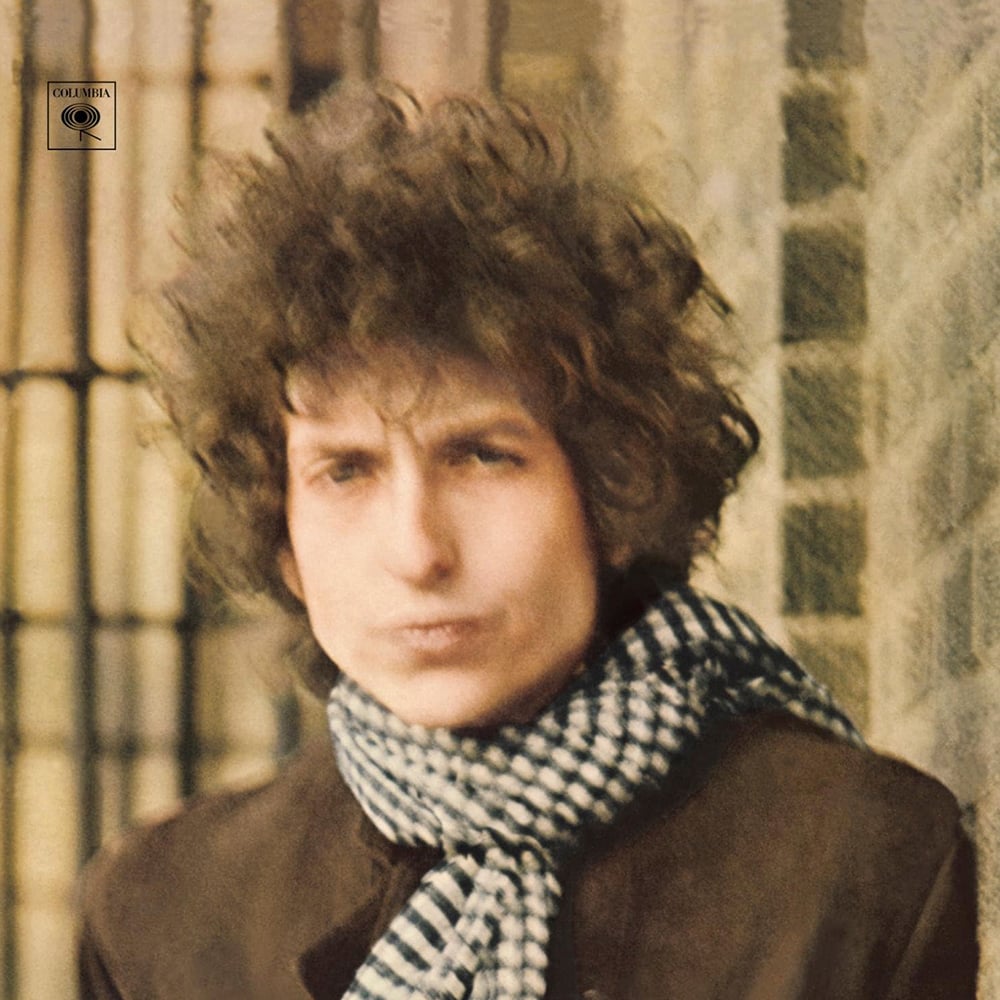

Penning the ballad on Thanksgiving, Dylan provided the music world with another blueprint for success. The song has been continuously covered ever since it was released on 1966’s Blonde on Blonde, with Joe Cocker providing perhaps the nearest competitor to Dylan’s original. Allegedly written for Dylan’s muse, Edie Sedgewick, the song is a romantic moment in the songwriter’s visceral canon.

It’s a departure for Dylan, too. The song is far more romantic than his usual output and is certainly toying with the indulgent saccharine style that so many pop singers fall victim to. But, what Dylan always possessed was his scything tongue. Singing “she breaks just like a little girl,” was one sharp moment in the track and hinted that even at his most loving, Dylan’s wit was whip smart.

[embedded content]

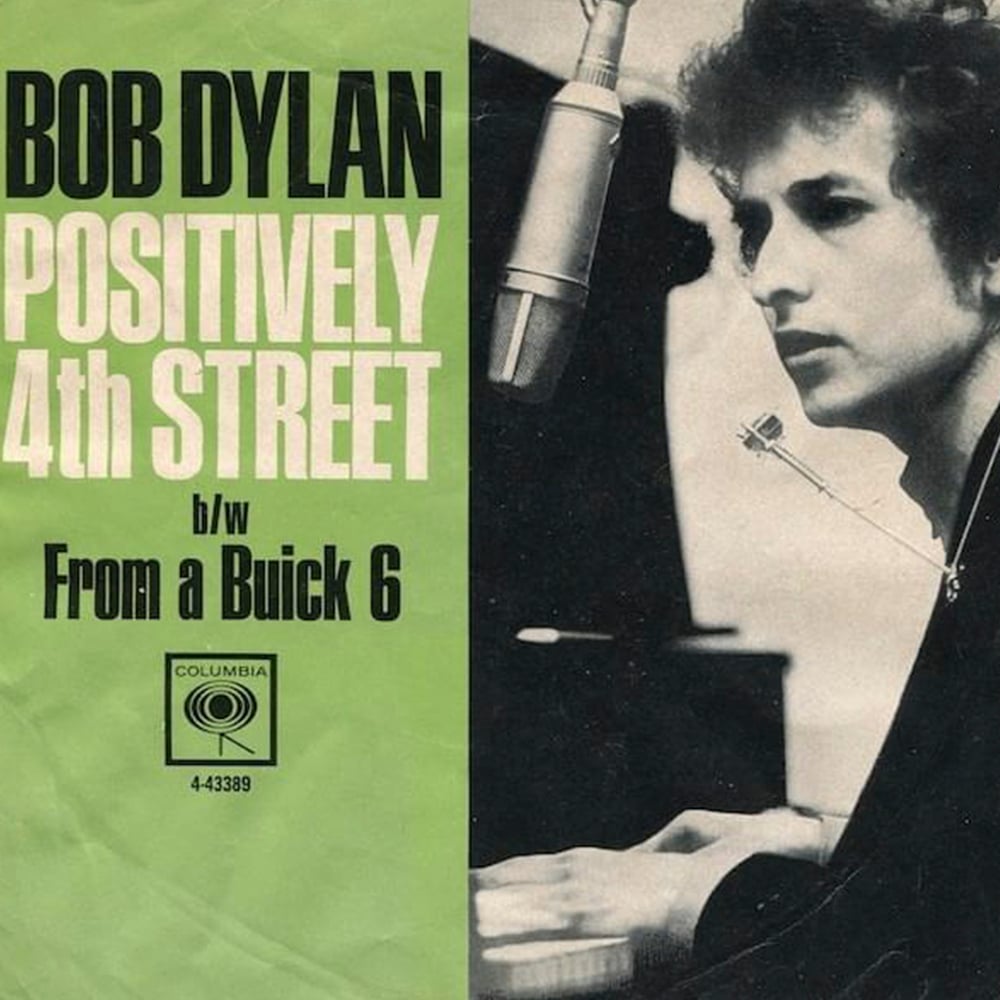

‘Positively 4th Street’

If there is a better break-up middle finger in music than the lambasting that Dylan offers up in ‘Positively 4th Street’, then it needs to make itself known. For the last verse Dylan penned the absolute searing dirge of, “I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes / And just for that one moment I could be you / Yes, I wish that for just one time you could stand inside my shoes / You’d know what a drag it is to see you,” and it crowned this folk-rock perfection king, and who’s asking?

The song itself is the twin brother of ‘Like A Rolling Stone’. It packs all the same punch and caustic acerbic wit, riding along on a slightly sweeter organ tone. It jangles in along on a soaring syncopated melody and beneath it all is a wondrous vivified indifference.

[embedded content]

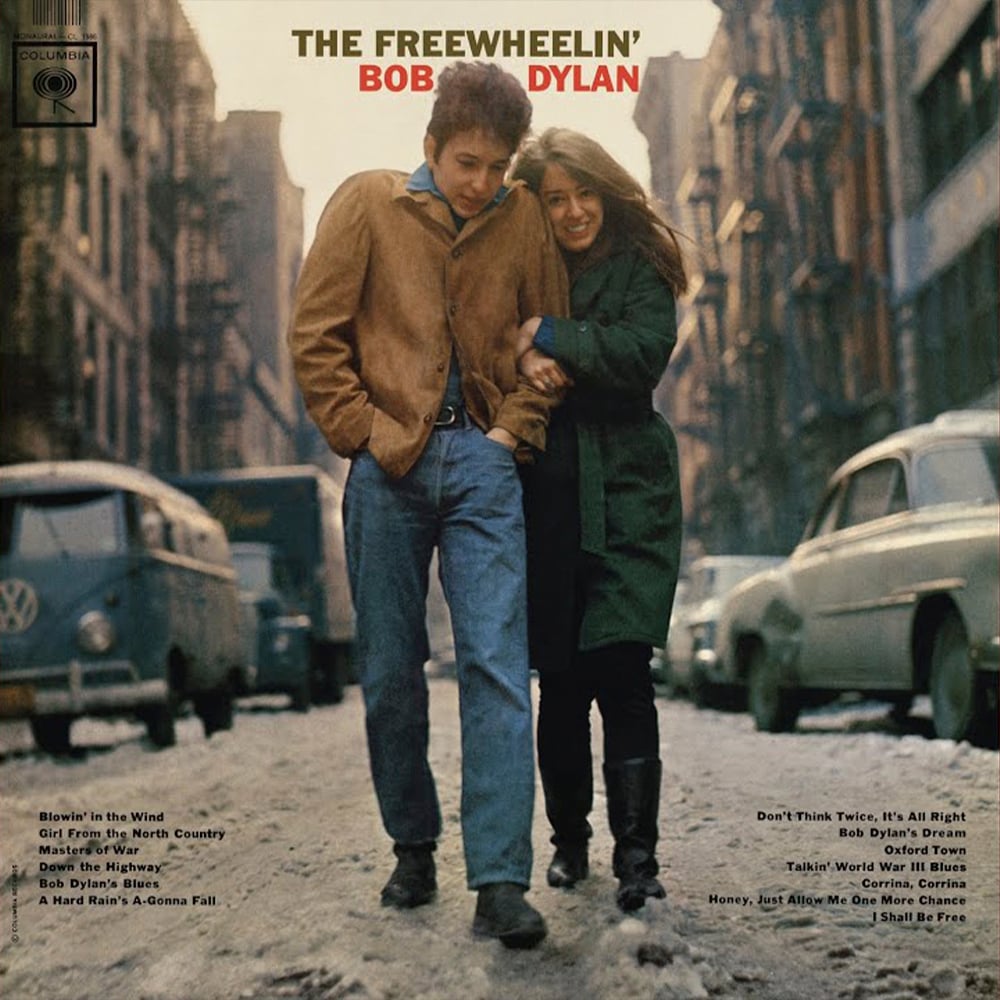

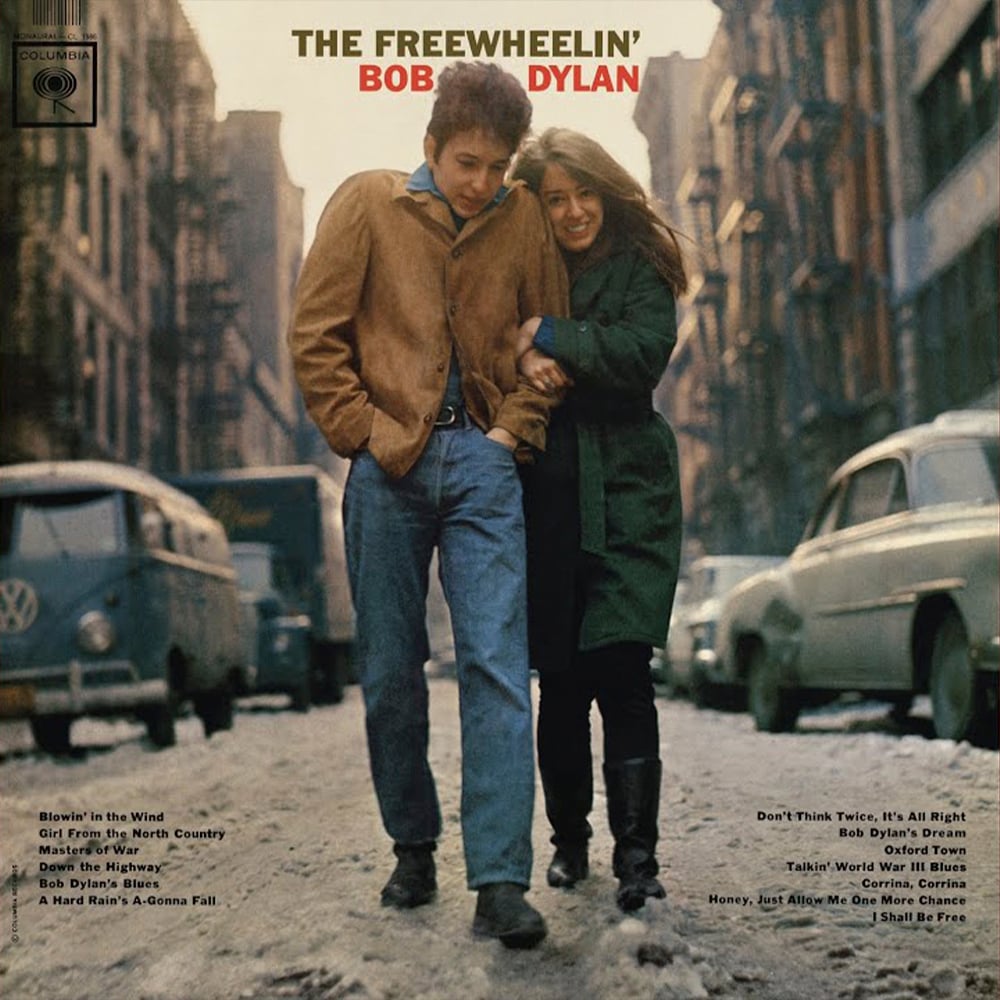

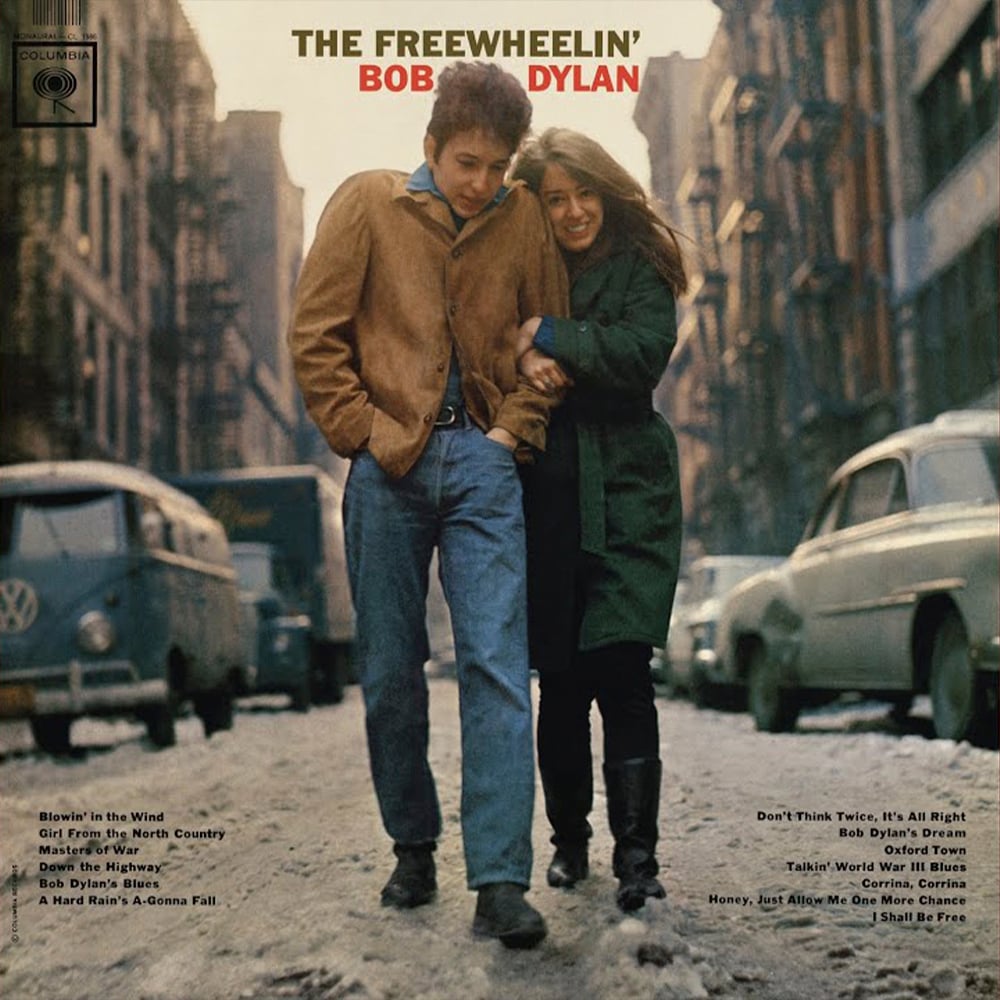

‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright’

The sheer number of singer-songwriters who have had a go at ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright’ is a testimony to its brilliance. Where most break-up songs are straightforward laments, Dylan captures duality and complexities with a song akin to postmodernist prose, which leaves you questioning the narrator and protagonist in equal measure.

All that being said, with this song Dylan unquestionably arrives at one of his finest melodies to boot. The plucking is very much in his key, and the solemnity dwells in the wheelhouse of his soul. Many might have had a go at it, but this track is a distillation of Dylan in a very pure form, and as such, it has never been bettered.

[embedded content]

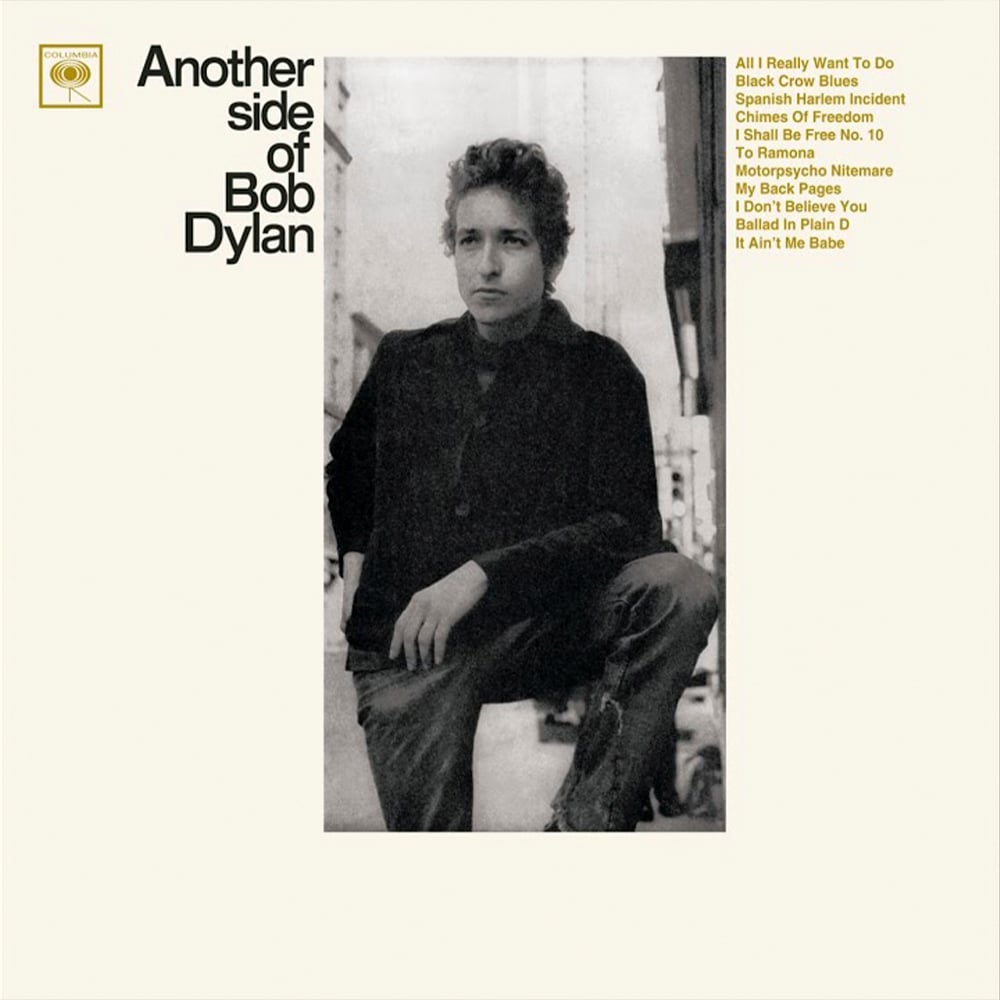

‘It Ain’t Me Babe’

By 1964, Bob Dylan was already considered a folk legend after making a name for himself in the underground Greenwich Village club scene and catapulting into stardom with his first three albums. But with his fourth studio release, Another Side of Bob Dylan, Dylan began to shy away from political ballads in favour of more personal songs about the human experience, which is evident in ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe.’

Although in true Dylan fashion, the song’s meaning has never been explicitly revealed, biographers and fans generally agree that the inspiration comes from his 1963 visit to Italy to search for his girlfriend at the time, Suze Rotolo, who was studying there. The song, along with the album in its entirety, was recorded on June 9, 1964, in a single all-night studio session, supplemented by “a couple of bottles of Beaujolais”.

It’s a song that certainly has its detractors, but they are only likely gathered because of the song’s immense popularity. Covered endlessly by some of music’s heroes, the track remains one of the most potent visions of Dylan’s ability to transcend genre and culture and provide a defining anthem.

[embedded content]

‘Hurricane’

The track, a protest song written by Dylan alongside Jacques Levy, details the imprisonment of middleweight boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. In the song, Dylan sings about the acts of racism against Carter and the subsequent false trial and conviction — it is pulsating with intent and purpose.

Convicted twice of a triple murder, Carter served almost 20 years in prison until he was released after a judge subsequently granted a petition of habeas corpus on procedural grounds in 1985. While in prison, Carter was visited by Dylan and was inspired to write his autobiography, in which he maintained his innocence. After their meeting in Rahway State Prison in Woodbridge Township, New Jersey, Dylan was inspired to write his song about Hurricane, but initially struggled to put his emotions on paper when the time arrived.

“Bob wasn’t sure that he could write a song [about Carter]… He was just filled with all these feelings about Hurricane,” Levy detailed about Dylan’s approach to the song. “He couldn’t make the first step. I think the first step was putting the song in a total storytelling mode. I don’t remember whose idea it was to do that. But really, the beginning of the song is like stage directions, like what you would read in a script: ‘Pistol shots ring out in a barroom night… Here comes the story of the Hurricane.’ Boom! Titles.”

It’s a song that bleeds authenticity all over the airwaves, propelling Dylan into a realm of storytelling that only Aesop can access.

[embedded content]

‘Blowin’ in the Wind’

Few songs can reach the level of mythology that ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ has. Closer now to theological text than perhaps any pop song has ever been, ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ now works as a mantra for allowing the troubles of life to flow through you as a breeze passes through cotton. The song may have been written in a matter of minutes, but it still lands squarely on the ground as one of Dylan’s timeless masterpieces.

Sure, if we want to be picky, we could refer back to countless other Dylan songs as having perhaps the same artistic value as this one. After all, can the best art be created in seconds rather than hours? But to dismiss the decades-long cultural impact of a song like this would be to refuse to see the whole picture.

The truth is, unlike any other Dylan song, this one has transcended everything we know about rock music. It doesn’t demand attention, it assimilates itself into our environment seamlessly, it doesn’t hang itself on a hook, despite the chorus being one of the most well-known around, and it certainly doesn’t need bravado to sell it. The beauty of this song is the same beauty that can be found in the smell of rain, the warmth of the sun and the, yep, you guessed, cool air of the wind. This song, above all else, is the very nature of why we love music — it gives so much more than it takes.

[embedded content]

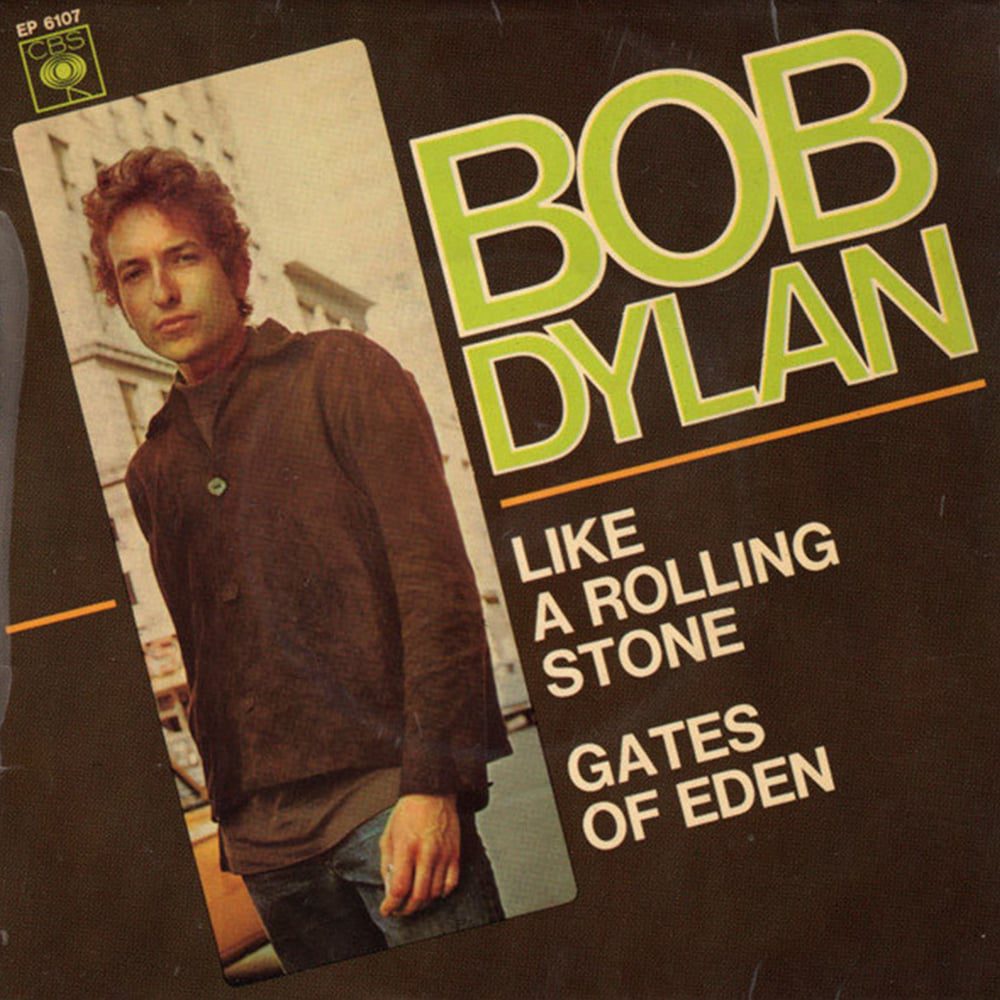

‘Like A Rolling Stone’

An article of this sort really rams home the subjectivity of music. It is a realm with few concrete truths, and anything is up for grabs in its rambling, undefined discourse. However, every now and again, there is a song that presents itself with such unflinching brilliance and mercurial bravura that every living thing under the sun just has to stand back and regard it.

You might not think it’s his best, but any musician, fan or inclined person worth their salt would have to agree that this song is on to something. Dylan lovers, loathers, and indifferentists alike all find something in this track, and for that alone, it stands out from the subjective stream of music with unapologetic individualism.

Wrath and rage has rarely met with such poignancy, and by the good grace of Dylan and whatever mystic figures of folk fate were weaving his back catalogue in this period, it’s all embalmed in an adrenalised sonic fuzz that figuratively slaps anyone half-listening into captivated submission.

If Dylan was the Jesus figure of the counterculture movement, then this was his moment of caustic condemnation in the temple of his own creation, and it proved one thing beyond doubt: hell hath no fury like Dylan scorned. This song is a masterpiece, and it has no problem telling that to anyone who’ll listen, and even those with their backs turned can get caught up in its glorious maelstrom too.

[embedded content]