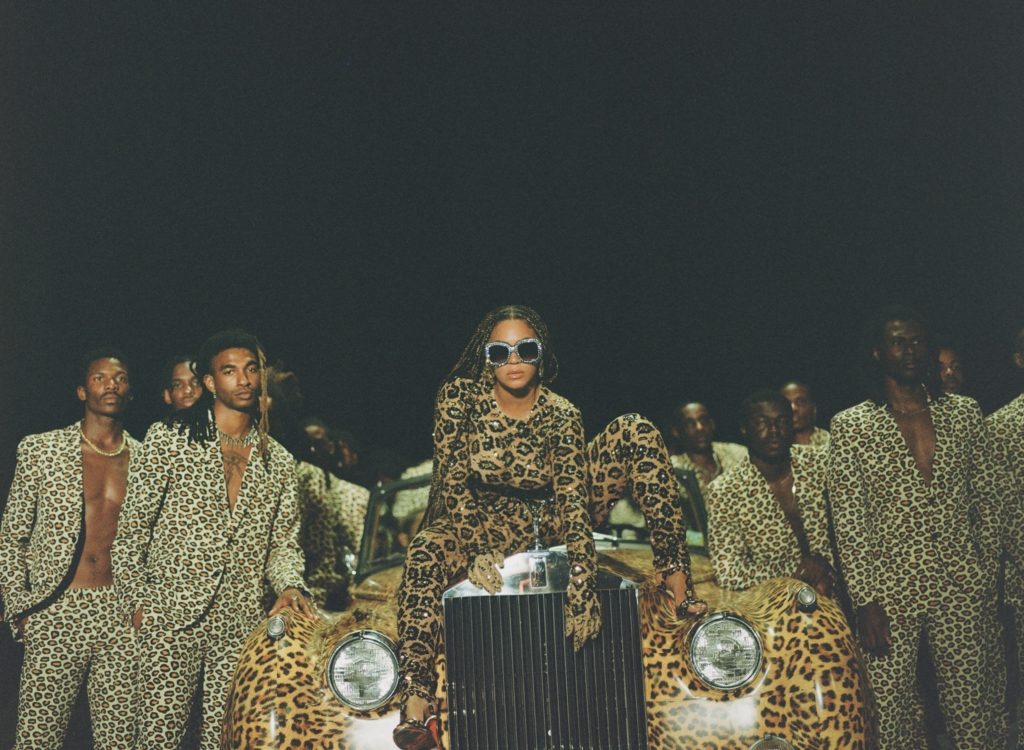

Beyoncé's 'Black Is King' Film Glorifies Her Message of Black Empowerment

Posted On

Posted On

Beyoncé has one-upped herself as she continues to redefine the “visual album” — from 2006’s humble B’day anthology to 2013’s world-stopping self-titled and 2016’s powerful journey through womanhood with Lemonade. Now, the megastar has achieved a creative pinnacle with Black Is King.

Released this past Friday (July 31) on Disney+, the visual album continues Beyoncé’s partnership with the House of Mouse following 2019’s live-action The Lion King. The artist-curated a soundtrack, Lion King: The Gift, which was presented as her “love letter to Africa.” Nearly a year later, the 85-minute Black Is King brings those songs to life through spectacular music videos threaded with voiceovers that reflect the beloved “circle of life” tale.

Beyoncé traveled across three continents to solidify Black Is King’s vision. “It all started in my backyard,” she told Good Morning America. “So from my house to Johannesburg, to Ghana, to London, to Belgium, to the Grand Canyon, it was truly a journey to bring this film to life.” Along the way, she gathered an impressive army of Black creatives to help boost the film’s message of Black legacy — including her husband Jay-Z, daughters Blue Ivy and Rumi, and The Gift’s African artists.

Nearly all of The Gift’s collaborators make appearances. They include Ghanian dancehall aficionado Shatta Wale; South African female vocalists Busiswa and Moonchild Sanelly; Nigeria’s millennial royalty Yemi Alade, Tiwa Savage, Wizkid, Mr Eazi, Tekno, and Burna Boy; Cameroonian singer Salatiel and homegrown American stars Jessie Reyez, Childish Gambino, Pharrell Williams, Kendrick Lamar, Tierra Whack, and Jay-Z.

In a surprisingly lengthy Instagram post at the end of June, Beyoncé expressed that Black Is King was a “labor of love.” “The events of 2020 have made the film’s vision and message even more relevant, as people across the world embark on a historic journey,” she continued, referencing the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement. “We are all in search of safety and light. Many of us want change. I believe that when Black people tell our own stories, we can shift the axis of the world and tell our REAL history of generational wealth and richness of soul that are not told in our history books.”

Beyoncé’s ties to Africa began long before the release of Black Is King, which she dedicated to her son Sir Carter. She transformed into a tribal queen during 2006’s “Déjà Vu” video, recruited Mozambican dance group Tofo Tofo to teach choreography for “Run The World (Girls)” and drew inspiration from Nigerian music legend Fela Kuti for “End of Time” (both off of 2011’s 4), incorporated Guinea-born Ismael Kouyate’s chants on 2013’s “Grown Woman,” hopped on Michelle Williams’ Nigerian gospel-inspired “Say Yes” in 2014, and referenced Nigeria’s Yoruba spirituality through 2016’s Lemonade.

Black Is King is not a direct retelling of The Lion King as we’ve come to know it. Rather, it’s a reimagination as it connects with the Black diaspora. 7-year-old actor Folajomi “FJ” Akinmurele is the film’s breakout star, playing a young Simba who grapples between the pressure to continue his father Mufasa’s legacy and finding his own identity. The hyenas are transformed into a biker gang (“Scar”), Timon and Pumbaa’s “Hakuna Matata” becomes a lavish lifestyle in a mansion (“Mood 4 Eva”), Mufasa’s funeral procession is draped in stark white that is representative of African traditions (“Nile”), and an older Simba is lured with hedonistic fantasies during Burna Boy’s “Ja Ara E.”

“You are welcome to come home to yourself,” Beyoncé begins the film, citing poetry by Somali-British writer Warsan Shire (whose work was also extensively used in Lemonade). “Let Black be synonymous with glory.” The idea of glory is the film’s foundation, as lush nature scenes, juicy fashions and bold tribal choreography remind viewers of their ancestral brilliance long before colonization tore it apart.

One of the stand-out moments of the film is “Already,” which shows just why Beyoncé is the best performer on the planet, as she ferociously goes toe-to-toe with Nigerian dancer/artist Papi Ojo. In the same scene, a crew of dancers revel beneath the Pan-African flag designed by Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey — a sharp statement of unapologetic Blackness.

“Brown Skin Girl” brought viewers (including this writer) to tears as an impeccably moisturized group of Black women embrace their melanin. “We were beautiful before they knew what beauty was,” Beyoncé states in the video. Naomi Campbell, Kelly Rowland, and Lupita Nyong’o (who are all name-checked on the song), as well as models Adut Akech and Aweng Chuol, who are shown in all their regality. Blue Ivy, who makes continuous appearances throughout the film, simply shines as she sings her part. For dark-skinned women who didn’t grow up having media representation, “Brown Skin Girl” served as a necessary salve.

The scene-stealing ladies for “My Power” (there’s even a pregnant woman dancing her heart out) that places Black female empowerment at the forefront, and an a capella version of soundtrack closer “Spirit” that lifts it to heavenly heights are additional highlights.

Along with its visuals, what makes Black Is King so compelling is its connections with Beyoncé’s actual career. The star drops various Easter eggs (which may or may not be intentional) from year’s past: the opening baptism scene is reminiscent of the ladies wading in the water during Lemonade’s “Love Drought” (which is a reference to 1803’s Igbo Landing, where slaves revolted by planning mass suicide) that could possibly insight a rebirth; the “Brown Skin Girl” debutante’s gowns were similar to the antebellum-era fashions of “Formation;” the red latex get-up from “Water” strikes a resemblance to Beyoncé’s bodysuit from the Formation World Tour; “Mood 4 Eva” nods to self-titled’s “Partition” as the robed singer reads the newspaper at breakfast, while also flipping whiteness on its head by trading the Mona Lisa found in 2018’s Louvre-centered “Apeshit” video for white butlers.

But Black Is King isn’t without its slight flaws. The same “Mood 4 Eva” that strips white colonizers of their value is also an excessive display of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s unattainable opulence, which calls to ongoing criticism of the couple’s capitalistic ways. The celestial “Find Your Way Back” video is a bit vain, with Beyoncé centering herself and her adoration for all things sparkly. And while the film is obviously based on fantastical fiction (it is a Disney production, after all), the “kings and queens” mentality isn’t an accurate representation of Black diaspora’s lineage.

“The Africans in Coming to America and Black Panther are cast as if from a past of unimpeachable glory and might; the Africa of pyramids and Kente cloth inlaid with gold,” authors Boluwatife Akinro and Joshua Segun-Lean wrote to Africa Is A Country last year. “It is easy to understand why Black Americans identify with these stories. They derive power from a particularly Afrocentric essentialism, which uses and exaggerates certain elements of pre-colonial Africa as an oppositional tactic to a western narrative of blackness as primitive and unaccomplished.”

Lastly, there is the issue of only using certain regions of the African continent for the music, which was the soundtrack’s problem in the first place. Upon the release of The Gift, some critics pointed out it focused too much on West African nations like Nigeria and Ghana, rather than other deserving countries in Central or East Africa (where The Lion King is actually based).

“The Gift doesn’t feature any Kenyan artists,” Ivie Ani explained for OkayPlayer. “Though it’s packaged as the sound of Africa, part of it feels like a one-dimensional dive into the Afropop/Afrobeats genre from West Africa … The Gift reinforces that visibility while forgetting the other side.”

Yet while Beyoncé is credited as the director, executive producer and writer of the film, she makes room for new voices. The rap sheet of creative minds of Black Is King is stellar. The co-directors include Ghanian filmmakers Kwasi Fordjour, Emmanuel Adjei and Blitz Bazawule; Jenn Nkiru (Nigerian-British); and Ibra Ake (the Nigerian creative director behind Childish Gambino’s “This Is America”). But it doesn’t stop there: From the avant-garde garments to the intricately braided hairstyles, nearly every single frame was curated by Black designers, stylists and hairdressers.

Black Is King is undoubtedly rooted in Blackness and is meant to uplift those who may be in search of their ancestry. But it’s also important to understand that Black people are still of value regardless if your bloodline is from royalty or hardworking everyman. Wherever your ancestors’ journey starts, one doesn’t hold more purpose than the other.

After watching the film, the only question one can pose is: where does Beyoncé go next? Black Is King is surely not the 38-year-old’s peak. But after recent years of being a representative of Black heritage, maybe it’s time for her to turn the mirror on herself for a self-reflective project. Whatever she decides to do, the impact she’s left on pop culture is too deep to ever be erased.