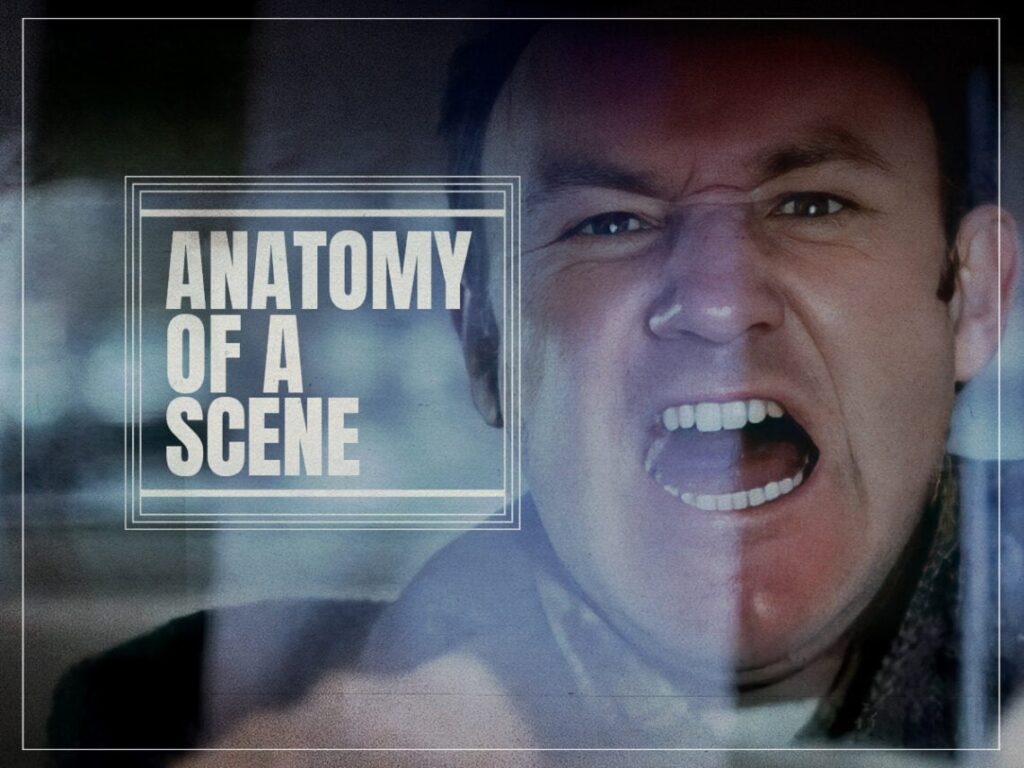

Anatomy of a Scene: ‘The French Connection’ reinvents the cinematic car chase

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / 20th Century-Fox)

Two-thirds of the way through William Friedkin‘s 1971 breakout thriller The French Connection, the lead character, a plain-clothes narcotics detective named Popeye (Gene Hackman), finally gets a shot at catching Pierre Nicoli (Marcel Bozzuffi), a member of a French drug cartel doing business in New York. The only problem is that Nicoli leaps onto a train just before Popeye can reach him. Launching into action, the detective commandeers a car from a passing driver and begins a mad chase through the busy streets of New York as the train speeds on an elevated track above him.

The scene unfolds over the course of eight minutes. With no special effects and almost no dialogue, it is hair-raising cinema at its most electrifying, and like many of Friedkin’s most daring feats of filmmaking, shooting it was extremely reckless and often illegal. During the chase, Popeye crashes the car multiple times, weaves in and out of oncoming traffic, and slams into the curb to avoid hitting a woman crossing the street with a pram.

According to Friedkin, the famous scene wouldn’t have happened if they’d shot the original script. Speaking to Entertainment Weekly for the film’s 50th anniversary, he revealed that the head of Fox thought the film was going to be too much like a documentary. “We didn’t have a chase one week before we started,” he said. “And my producer and I decided to take a long walk in New York from an apartment I was renting at 86th Street.” They ended up walking 55 blocks, soaking in the everyday hustle and bustle of the city, from the smoke rising from the streets to the rumble of the subway. From that stroll, they constructed the concept for the chase.

When it came time to shoot the scene, Friedkin went all-in on realism. One of the most riveting aspects of the sequence is the different camera angles. It isn’t just shot from a distance. It’s shot inside the car, looking at Popeye as he careens through the streets with a look of maniacal determination and from the hood of the car as if the viewer were hurtling along at breakneck speed. It will make your stomach lurch even if you’re watching it on a small screen, and it was largely the result of the limited budget.

Instead of using cranes or a camera car, Friedkin got into the car with Hackman’s stunt driver Bill Hickman, cinematographer Enrique Bravo, and NYPD detective and consultant Randy Jurgensen, who would show his badge to any police officer who pulled them over. They also mounted three additional cameras to the vehicle’s exterior to maximise the footage they could get in a single shot. They then let loose on 26 blocks of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn.

“There were a lot of accidents, a lot of things that happened that we didn’t think about, and it’s a miracle that nobody got hurt,” Friedkin told Entertainment Weekly. “I wouldn’t do that today. It was very dangerous. I can’t tell you how much.”

He did admit to going 90 miles per hour, ignoring red and green lights, and blowing through oncoming traffic. To watch the scene with this knowledge adds a whole new layer of anxiety. Friedkin wasn’t exaggerating when he said that someone could have gotten hurt. Someone could easily have died as well.

The film went on to earn eight Academy Award nominations and won five, including ‘Best Picture’ and ‘Best Director’ for Friedkin. It might have attained these accolades without the chase sequence, but it’s difficult to imagine the film without it. It was the director’s first calling card after a fractured, unsatisfying string of early films that never fully showed his potential as a filmmaker. Thanks to the car chase sequence in The French Connection, his visceral, guerilla approach to the medium became instantly unforgettable, and his ability to weave it into a narrative was on full display.

Looking back on the scene 50 years later, Friedkin was careful to sound chastened and often tried to reframe himself as a young filmmaker who didn’t yet understand the risks he was putting himself and his crew through. “I was like Captain Ahab pursuing the whale,” he concluded. “[I had] a supreme confidence, a kind of sleepwalker’s assurance. As successful as the film was, I wouldn’t do that now. I had put people’s lives in danger.”

[embedded content]

Related Topics