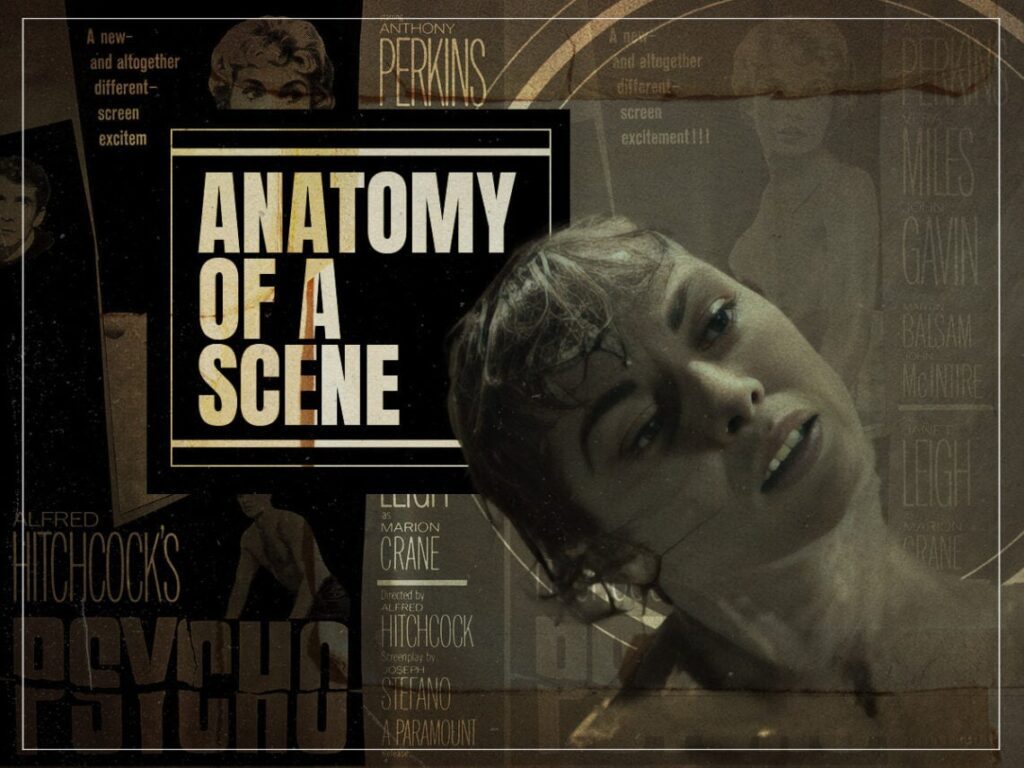

Anatomy of a Scene: ‘Psycho’ changes the entire language of cinema with a single shower

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Paramount Pictures)

Alfred Hitchcock was no stranger to pushing the boundaries of cinema, pioneering techniques that would soon become industry practice, and upending convention to shock and entertain. However, if there’s one scene that perfectly captures the essence of what the ‘Master of Suspense’ was all about, it’s Psycho.

The shower sequence isn’t just one of the most famous in the history of moving images; it’s also one of the most iconic and influential. Everything Hitchcock wanted cinema to be—and the impression he made on it—are present and accounted for in less than a minute of footage that conspired to help usher in a new way of thinking among the industry’s foremost auteurs.

Hitchcock insisting that theatres deny entry to patrons who weren’t seated by the time the film started wasn’t just a gimmick; it was pivotal to getting the most out of Psycho. The intentionally misleading marketing had promised one of the director’s signature high-concept thrillers, and everybody assumed Janet Leigh would be the focal point because she was the biggest star in the cast.

Of course, that’s exactly what the filmmaker wanted everyone to think before he orchestrated a rug-pull for the ages by having her murdered midway through. This action reinforced the notion that all bets were off as to what the rest of Psycho would entail and reiterated the maestro’s credentials as a technical and artistic virtuoso who was doing things on film that nobody had ever done before.

That doesn’t even include the flushing toilet, which was itself a slice of history when no movie had ever shown audiences the swirling aftermath of a crapper on the silver screen before, but it’s easy to overlook that particular first when the remainder of the shower scene became notorious at the time and inspirational after the fact for the way it pushed the language of the medium forward.

It was almost as if he was running through a checklist of things that others weren’t committing to celluloid and then ticking them off one by one. Nudity? In a roundabout way, Leigh and her body double, almost baring all for the cameras to cause much pearl-clutching among censors and patrons.

Rapid-fire editing, extreme closeup, and Bernard Hermann’s seminal composition – aptly titled ‘The Murder’ – were woven seamlessly together to create audiovisual chaos, the likes of which had never been seen. The set was specially constructed so the camera could get in as close as possible, and the imagery works in such perfect synchronicity with the edits that it gave rise to the urban legend the knife could actually be seen piercing the abdomen of Marion Crane.

Violins had typically been used to signal opulence or romance, but Hitchcock used them for sheer terror. The sound design made by a melon getting knifed to within an inch of its fruity life was simple enough but deployed in such a way that cinemagoers were left feeling queasy by the time the blood swirled ominously down the drain, Crane’s life having been extinguished and Leigh’s star power failing to make it anywhere close to the end credits.

Hitchcock had always been a voyeuristic filmmaker happy to let his viewers feel like they were part of the same conversation, and watching a murder unfold in front of their eyes was the next logical progression. It’s not about what happens in the scene, though; it’s about how the director wants the audience to interpret it, which they fell for hook, line, and sinker.

The nudity, the knife cleaving flesh, and the rampant bloodletting are all implied more than they’re seen, and introducing murder to the masses as the most talked-about scene in a box office smash hit helped pave the way for the incoming ‘New Hollywood’ generation to tackle taboos and break down their own barriers, turning what had previously been cinematically unspeakable into mainstream concerns.

And to think, Hitchcock accomplishes all of that and more in a scene that only runs for little over three minutes from beginning to end, with the rapid-fire assault by the then-unknown assailant accounting for less than a third of that time.

[embedded content]

Related Topics