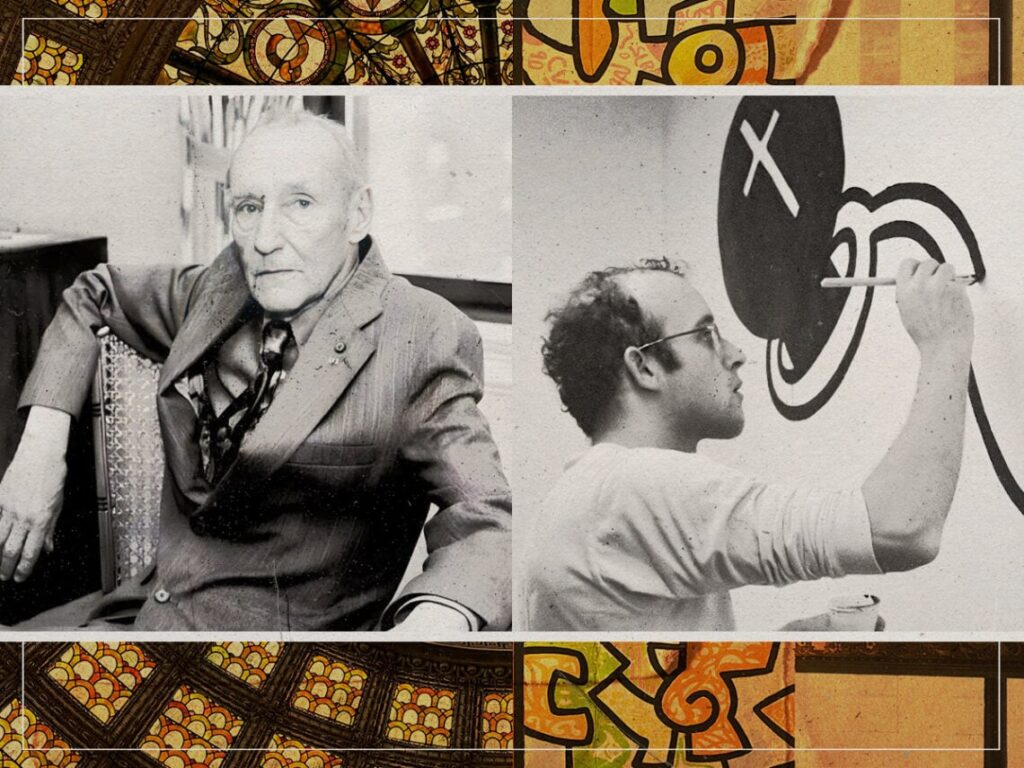

A New Perspective: how William S. Burroughs inspired Keith Haring

Posted On

Posted On

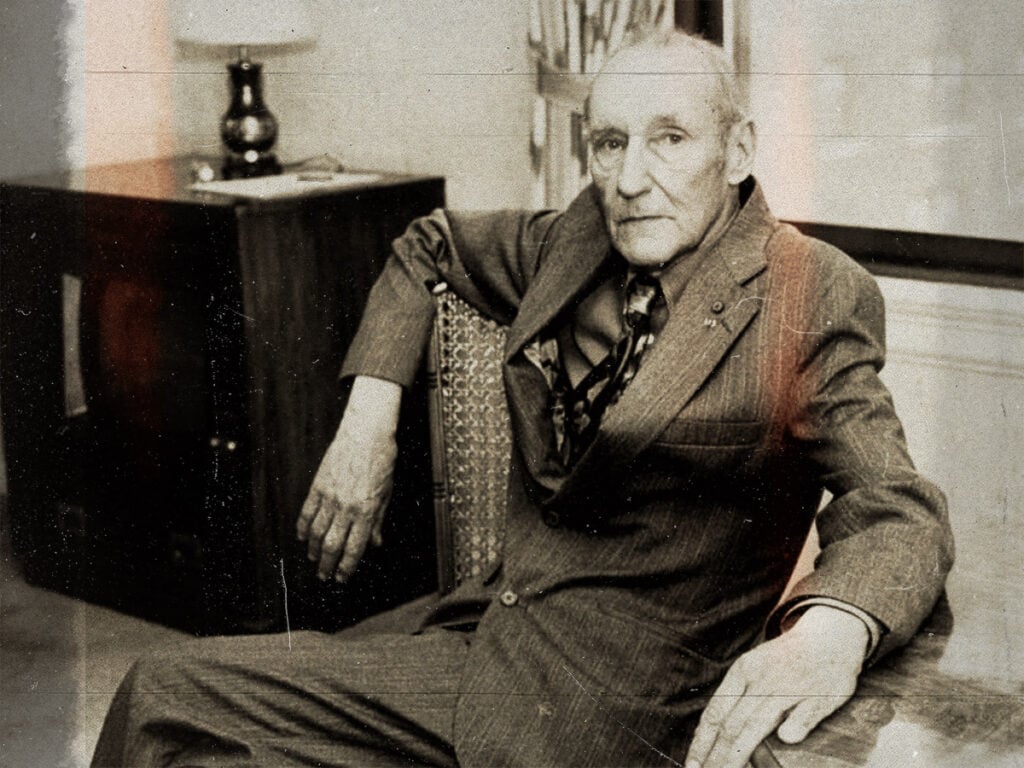

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy / Rob Bogaerts)

As one of the tragic casualties of the AIDS outbreak, Keith Haring joins the likes of Derek Jarman and Freddie Mercury as part of an immortal image of strength in the face of adversity. These three artists operated in different artistic media and walks of life. However, each underwent scrutiny based on their sexuality and decided to embrace who they were in bold, stoic artistic expression, whether it was unrivalled stage command, provocative filmmaking or pop art.

Keith Haring was a visual artist best known for his social activism and often associated graffiti-inspired artworks. His distinctive style employed bright colours, bold lines and recurring motifs, including energetic stick men, barking dogs and large love hearts. More often than not, these quirky cartoons expressed love and happiness with a sociopolitical subtext of equality, peace and harmony, especially with regard to the LGBTQ+ community.

Often, Haring’s art addressed sociopolitical issues more directly, using the same language of optimism and colour to illuminate the woes of the AIDS outbreak, racial segregation, and the crack cocaine epidemic. These issues were rife in New York City throughout the 1980s, where his powerfully poignant, uplifting, and universally accessible art struck its most harmonious chord.

Since his death at the age of 31 in 1990, Haring’s name has continued to circulate in the artistic world. Over three decades on, his legacy shows no sign of faltering, with his work frequenting high-profile exhibitions, auctions and fundraising events. Notably, the Keith Haring Foundation, established in 1989, continues to raise awareness for AIDS sufferers and supports children’s programmes and education through art.

Today, you would expect hefty sums to pass hands at a Haring auction, but at the very beginning of his career, he gave it away for free. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, Haring would create murals and street art inspired by the burgeoning graffiti trend in New York. With permission, he would adorn subways, paving and buildings with his artwork, often using temporary chalk-based paints. Over time, he gained recognition and was commissioned to tackle more expansive murals and establish a presence in the city’s competitive exhibition trail.

Most palpable in Haring’s work were influences like cartoonists like Walt Disney and Dr. Seuss and pop art pioneers like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. Indeed, the latter pair were behind Haring’s decision to move to New York City in 1978 from his hometown of Reading, Pennsylvania.

As his activism work might suggest, Haring understood the limitless nature of art. “I am becoming much more aware of movement,” he wrote in his journal in 1978. “The importance of movement is intensified when a painting becomes a performance. The performance (the act of painting) becomes as important as the resulting painting.” In accordance with this notion, Haring’s artworks became increasingly conceptual and participatory over time.

Several notable artists could be ascribed to several artists. However, perhaps most intriguing was the colossal influence of Beat Generation writer William S. Burroughs. The nonconformist rogue challenged him to see the bigger picture, to innovate by combining different media and to understand the importance of satire and rhetoric.

Speaking to David Sheff in a 1989 interview for Rolling Stone, Haring recalled the first time he heard of Burroughs. “At first, I was just working in the same style as I was at home. But then all kinds of things started to happen,” he said. “Maybe the most important was that I learned about William Burroughs. I learned about him almost by accident – like almost everything else that has happened to me, sort of by accident-chance-coincidence.”

Beyond Burroughs’ general artistic approach, Haring admired the famous “cut-up” method the writer devised with Brion Gysin for creative writing and idea generation. Haring told Sheff that the process “became the basis for the whole way that I approached making art” at a pivotal moment in his career. “The idea of their book, The Third Mind, is that when two separate things are cut up and fused together, completely randomly, the thing that is born of that combination is this completely separate thing, a third mind with its own life.”

“I used the idea when I cut up headlines from the New York Post and put them back together and then put them up on the streets as handbills,” Haring recalled of some of his early street-based work. “Sometimes the result was not that interesting, but sometimes it was prophetic,” he added. “The main point was that by relying on so-called chance, they would uncover the essence of things, things below the surface that were more significant than what was visible.”

Burroughs and Gysin popularised the technique in the 1960s and began publishing related poetry and prose entries in a series. Many of these eventually contributed towards the 1978 book The Third Mind. The word transplantation technique became notably virulent among musicians, famously guiding the songwriting achievements of David Bowie, Thom Yorke and Kurt Cobain.

[embedded content]