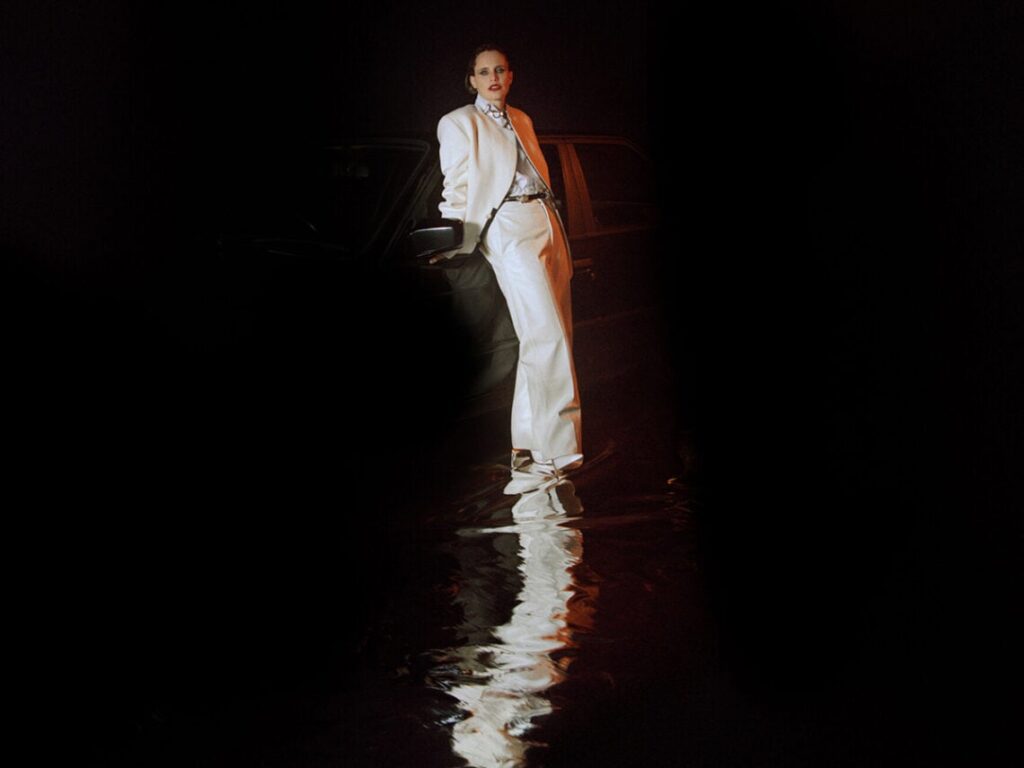

‘Wuthering Heights’ movie review: A surprisingly tame adaptation of Brontë’s feral love story

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Warner Bros.)

Emerald Fennell – ‘Wuthering Heights’

Since its initial publication in 1847, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights has taken on a life of its own.

Despite being largely dismissed during the author’s lifetime, its violent tale of doomed love, revenge, and generational loose ends has inspired everyone from Luis Buñuel to Kate Bush, giving rise to ballets, television series, and pop songs. Now, Emerald Fennell has turned her talents to the tragedy of Cathy and Heathcliff, cramming every second of the two-hour and 15-minute running time with sparkles, fog, and deliciously pornographic sound design. What sits beneath all the glitz, however, is a surprisingly staid love story that is much more in keeping with Shakespearean tragedy than the feral shagginess of Brontë’s imagination.

Like most directors who have adapted Wuthering Heights, Fennell has chosen to use only the first half of the novel. Towards the beginning of the story, Cathy Earnshaw’s father (Martin Clunes) brings home a foundling, an abused boy who she christens Heathcliff. Played by Charlotte Mellington and Owen Cooper in the first part of the film, the children develop a powerful bond, romping through the rain-whipped moors and pledging their undying devotion to each other. By the time they morph into Margot Robbie and a wild-haired, bearded Jacob Elordi, their pranks and one-upsmanship carry a strong undercurrent of sexual tension.

While the novel leaves most of the eroticism as subtext, Fennell, who made audiences gasp with scenes of cum-slurping and grave-fucking in 2023’s Saltburn, has predictably literalised it. In one scene, a dumbstruck Cathy watches as two servants get down to business in a horse stable, whips and bodice-ripping included. Silently, Heathcliff comes up behind her and covers her eyes and mouth, a position she will pitifully try to recreate with the decidedly vanilla man she marries.

The tragedy takes hold when Cathy meets the newly arrived neighbour, the fabulously wealthy Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif). He is dull but adoring, and Cathy, who lives in relative squalor with Heathcliff and her gambling, alcohol-addled father, is enchanted by the opulence of his home, the fawning of his young ward, Isabella (Alison Oliver), and the promise of a life of luxury.

It is here that Fennell’s adherence to the source material gives way entirely. Aside from cutting out various characters and lopping off the entire second half, she casts a servant (Hong Chao) as the villain, a conniving childhood friend-turned-enemy determined to keep Cathy and Heathcliff apart. Through her schemes, the would-be lovers fall prey to a colossal misunderstanding that sends him into years of self-imposed exile and her straight into the arms of Linton. In the novel, Cathy and Heathcliff are their own undoing. In Fennell’s retelling, they are the victims of a jealous, two-dimensional supporting character. It’s a choice that routs the self-destruction at the heart of the novel, and no amount of ragged breathing and outdoor humping can distract from the timidity of this revision.

From the midpoint on, Fennell lets style take over. With anachronistic costumes and production design so flamboyant it makes Tim Burton look like a documentarian, the story crumbles into a carnivalesque collage of Instagram-ready images. With Charli XCX’s original music, this portion of the film is an unabashed music video featuring all the gauzy lushness you’d expect of Lana Del Rey. With Robbie’s 21st-century face, it looks more like a perfume ad than an adaptation of literature’s most feral romance.

When Heathcliff returns, he’s wearing a ruffled collar and a tiny gold earring worthy of your favourite barista. He is rich now, and one good shave has rendered him nearly unrecognisable. There was an audible gasp from the audience when he appeared on screen. Or perhaps it was a sigh of relief. Without Elordi’s animalistic passion and carefully shielded vulnerability, it is very difficult to find an emotional port in this hurricane of aesthetics. His casting was controversial, since Brontë describes Heathcliff as being a “dark-skinned gipsy” rather than a white Australian, but his performance provides the soul and longing to a film that otherwise flounders in its production design.

Fans of the book will find the direction of the second half downright blasphemous, but the writing is on the wall from the moment Isabella recounts, with comedic fervour, the story of Romeo and Juliet. This is a Shakespearean tragedy, not the thorny, barbaric, hero-less story that Brontë created. When the novel was published, one critic expressed disbelief that the author had not committed suicide before finishing 12 chapters, calling it “a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.” You would think that Fennell would be the perfect candidate to bring “vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors” to the screen, but alas, there is very little about the film that could be described as unhinged, offensive, or even haunting. She reportedly hoped that it would be this generation’s Titanic, and that is exactly what she has delivered.

For those who feel short-changed by this, you might want to go back and watch Saltburn. It is, whether intentionally or not, much closer in tone and even plot, in some instances, to what Brontë devised. That scene in which a character has sex with a freshly-dug grave? That’s in Brontë’s novel (albeit implicitly). An outsider who systematically and violently replaces an entire family? That’s also in the novel.

That said, no one, including Fennell, has ever managed to fully capture the brutality, intensity, and elusiveness that have made this book such a literary earworm. The tormented love between Cathy and Heathcliff, a love that crosses from childhood to death and beyond, defies a faithful retelling, especially for those wanting to turn the villainy and selfishness of the central characters into something purely romantic. Fennell’s film is a sugar rush and a tearjerker. It’s stuffed to the gills with meticulous design, and it even, in some instances, draws directly on the text of the novel for dialogue. Ultimately, however, it fails to recreate that sense of timelessness and untameable passion that Brontë did. Fortunately, the book is still in print.

[embedded content]