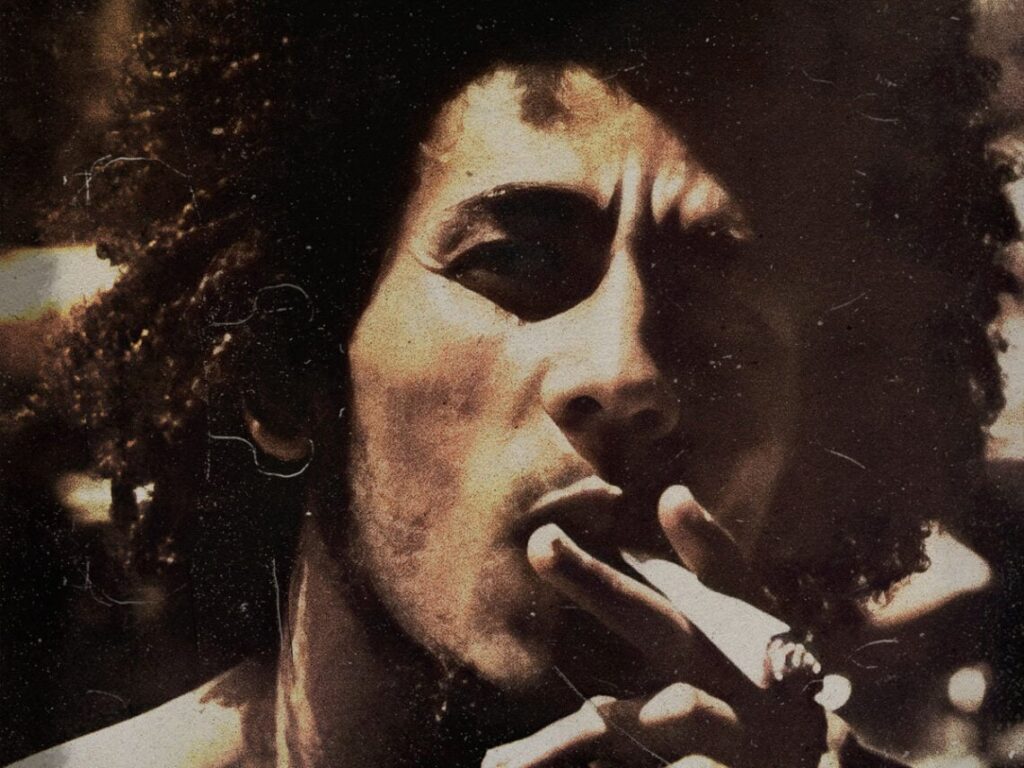

Bob Marley was forced to defend reggae as a viable form of pop music: “It’s like cooking”

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Album Cover)

As one of the most successful greatest hits compilations of all time, Bob Marley’s Legend has been supplying the chill vibes for over 40 years now, but it’s also been reinforcing a subtle distortion of the man it’s ostensibly immortalising.

The cherry-picked tunes on Legend, which was released in 1984, three years after Marley’s death, lean into the idealistic ‘One Love’ image of the Jamaican icon as stoned, noble, ‘singing sweet songs’, and side-step most of his forays into thornier rebel politics, social issues, and Rastafarian beliefs. It’s not the worst crime in the world to put an artist’s cuddliest and most accessible material on a cash-grab compilation, but the effects of that decision have had consequences that have stretched beyond Marley’s legacy.

Reggae music itself, which has a long and proud tradition of speaking truth to power, was a building block and community ally of punk music in the 1970s; but today, that edgier dynamic has been largely obscured, at least among casual observers, by the music’s immediate associations with weed, island holidays, and UB40.

Rather than being treated like a legend everywhere he went during the prime of his career in the 1970s, Marley was often treated like the canary in the coal mine by British and American journalists. He was, in terms of recognition and record sales, the biggest international name in reggae, but year by year, an anticipated, wider explosion in reggae music’s popularity, particularly in America, failed to arrive. Stars like Peter Tosh and Jimmy Cliff experienced pockets of mainstream success, but the media and record executives alike seemed convinced that something was preventing reggae artists from achieving mass appeal.

Marley himself had the issue pretty well assessed, feeling that white-owned record labels and radio stations in America had little motivation to play a form of music made for the purpose of “Black unity”, as he called it. The easier answer from critics was to simply point out that reggae was slow and ill-suited to catchy hooks or dancing, due to a rhythmic emphasis on the first beat instead of the second. This was a stupid contention, but Marley was kind enough to respond to the notion once in a 1976 chat with the Associated Press.

“If they got space, they dance to it,” Marley said, referring to the evidence he’d witnessed first-hand at dozens of his own gigs, attended by fans of all races, ages, and backgrounds across the US, “If they go in a theatre, they stand up at their seats and shake. The beat is bomb, bomb, bomb, bomb; the rhythm goes on. You must dance creatively to reggae music. You must do whatever you want to do with dancing. It’s like cooking; one cook is different from the other cook.”

Just a few months after this interview, Marley would be shot in an assassination attempt in his native Jamaica, preventing him from playing any shows for more than a year. When he finally returned to a stage, it was back at the scene of the crime, part of what he saw as a holy mission from God to bring peace to the island. Marley’s music, however, didn’t take geography into account.

“We don’t have different name for people who live in America and people who live in Jamaica,” Marley told Newsday in 1978, “We have just one name: Rastafari. Queen rule England; this mon rule that, and yet only one God. God rule the world.”

As for whether he was concerned about reggae’s supposedly sputtering popularity in America, he could only laugh. “We control reggae, mon,” he said, “Nobody can tell you how big reggae is. We make reggae what reggae is, see? No record company”.

[embedded content]

Related Topics