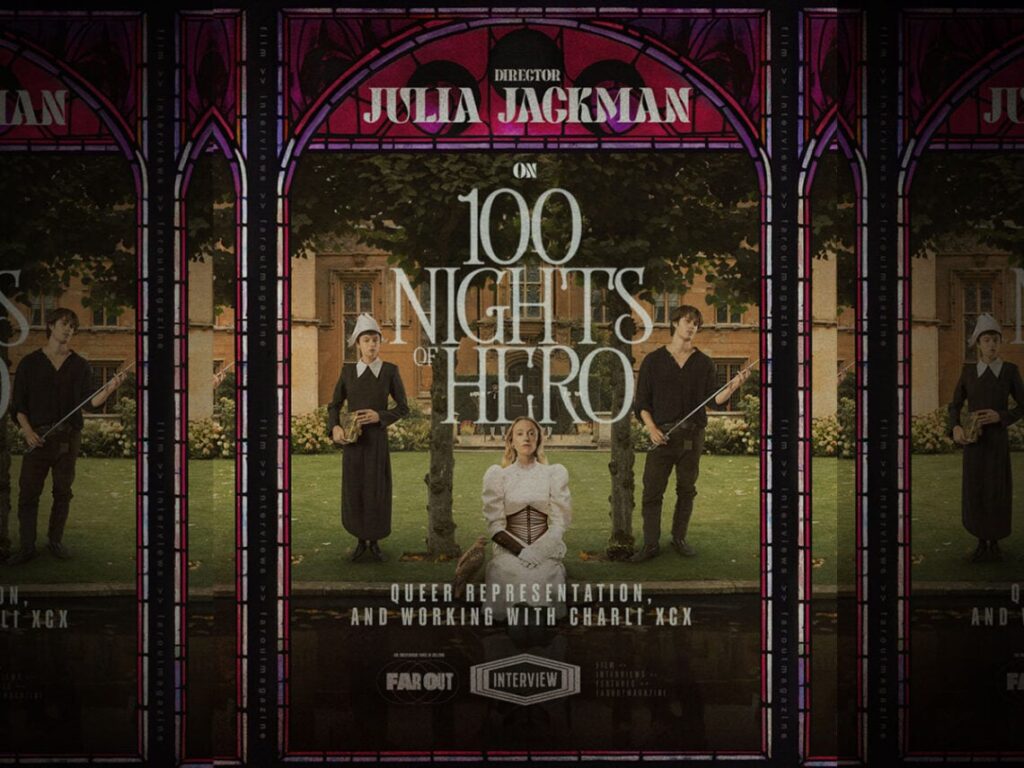

Julia Jackman discusses her modern fairytale ‘100 Nights of Hero’, queer representation, and working with Charli XCX

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / IFC Films)

It’s rare to stumble upon a modern film that truly feels like a fairytale, but Julia Jackman’s 100 Nights of Hero is just that.

Like all good fairytales, though, the story is firmly rooted in reality, underscoring its fantastical visuals with bold explorations of gender inequality, sexuality, and the discovery of the self, as comedic as it is heartfelt, this is a unique piece of filmmaking that finds hope among ruin, and it’s hard to believe that this is only Jackman’s second feature.

The filmmaker didn’t always know she wanted to make films, but she pinpoints a summer camp which put on plays in both English and Sign Language as a pivotal moment in her creative development when she was young. “I’d lost quite a lot of my hearing when I was 11, and my mom and dad enrolled me, and that was really transformative for me in terms of creativity,” she tells Far Out. “I did a lot of sports, and I didn’t think of myself as super creative, but I remember that feeling of collaboration and family and putting things together.”

Fast forwarding to her mid-20s, Jackman caught a screening of Xavier Dolan’s Mommy, and it flicked a switch. “To see someone from Canada, close to my age, just doing it – making this film that I found completely thrilling – I think that really inspired me.” Cinema soon became Jackman’s go-to medium, making her debut feature, Bonus Track (based on a story conceived by Josh O’Connor) in 2023.

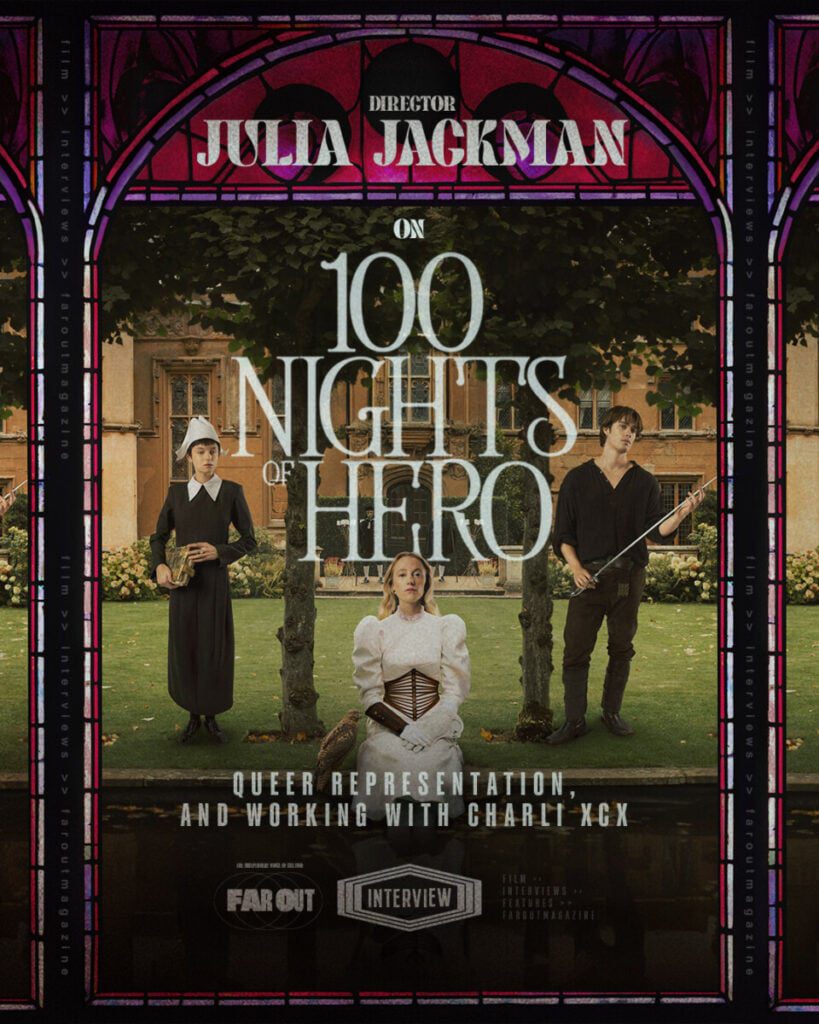

100 Nights of Hero is a lot bolder in its execution, however, with sets which look like they’ve been lifted from a gorgeously illustrated colouring book that Jackman has carefully injected with vivid hues, depicting a world that feels tethered to no specific time or place. Based on the graphic novel by Isabel Greenberg, Jackman first read the story when she had “just started” making films, and she knew that it was something she wanted to tackle someday. But was she ready just yet? She couldn’t shake the feeling that she needed to make it, though, and soon it started to take shape in her mind.

Jackman explained, “I read it, and loved it, and thought, ‘One day I would absolutely love to see this on screen.’ After a little bit, when I made some more films, I thought, ‘Maybe that could be me. And I was just really struck by being transported to another world, and the dry humour, but also the hopeful anger. It had all of these themes that really chimed at me, and obviously I love a gay love story as well”.

When an idea refuses to leave your mind, you have to give it the space to grow, and for Jackman, she knew that this tale of queer repression – which is allowed to blossom into something beautiful as main character Cherry (Maika Monroe) starts to fall for her closest friend and confidante, Hero (Emma Corrin) – was something she had to tackle.

Jackman explained, “We’re not a monolith, so sometimes something really speaks to you, and sometimes it doesn’t, and I know that that’s where this could fall. But I’m all for variety in queer stories, and I love the outrageous elements of other queer stories, but for this one – because repression is so baked into the world – I really wanted to show that, even though they’re adults, this sort of queer coming of age element, where we can see the love almost before Cherry really acknowledges it.”

100 Nights of Hero tenderly explores this growing attraction between Cherry and her maid, Hero, which forms while Cherry’s husband, Jerome, leaves for one hundred days. He allows his cocksure friend Manfred to stay at the house, who is adamant that he can successfully seduce Cherry, but instead it’s Hero that Monroe’s character finds a sense of security with.

Adding, “When straight is the default, you can have that feeling with such a close friend, like… this is the person I can be myself around. This is the person who understands me. This is the person I relax around and am fascinated by. And then at some point, something sort of clicks into place, and I wanted to show something where the intimacy… it was just sort of naming what was there. The falling in love was naming what was there before the character was even aware of it herself. I guess that’s a queer canon event.”

So, ‘How do you tell a love story that retains these fairytale elements while simultaneously exposing the fragility of masculinity and the long history of female and queer repression?’ is an important question, because tone is a tricky thing to master when your fairytale narrative is rooted in the grim reality of societal oppression, but Jackman was conscious of mastering the right tonal atmosphere.

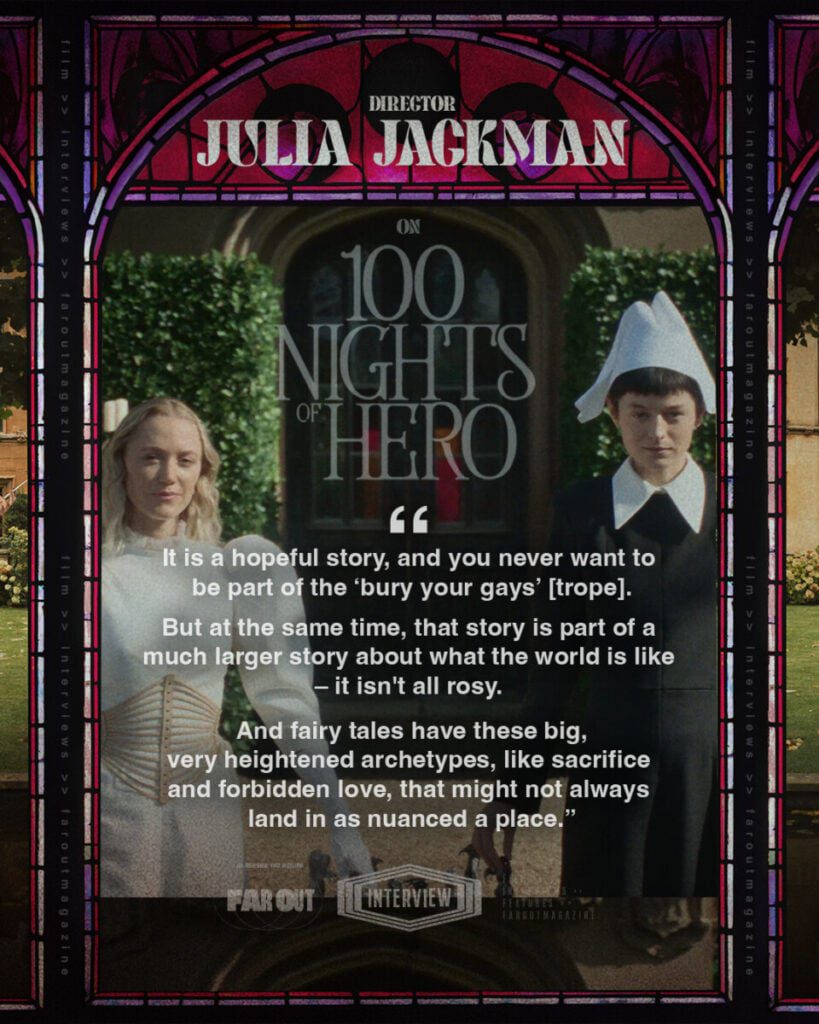

Noting, “It is a hopeful story, and you never want to be part of the ‘bury your gays’ [trope]. But at the same time, that story is part of a much larger story about what the world is like – it isn’t all rosy. And fairy tales have these big, very heightened archetypes, like sacrifice and forbidden love, that might not always land in as nuanced a place. But I do think that there is this kind of hopeful defiance at the end that I was hoping would lift it out of that.”

Jackman admits that mastering the right tone was a “delicate dance,” and while there’s a camp element to the film, she didn’t want her actors to necessarily play their characters as such, in turn allowing this sensibility to naturally occur. “There’s so much camp in male posturing and these rigid roles that we’re asked to play. There is a theatre to it,” she says, explaining how she sat down with her actors and “talked about how the film could be very camp, but that each character had to believe the world they were in.”

This campness is apparent in the character of Manfred, played by Nick Galitzine, who brings an innate and effortless charm to the role. He’s an interesting villain because he’s both pathetic and ridiculously attractive – there’s something to him that makes us fall for him ever so slightly, even though he possesses an obnoxious self-assuredness. Jackman was set on crafting a character who wasn’t the one-dimensional image of a toxic male, explaining, “I think when these really misogynistic figures are obvious, they’re almost less dangerous.”

Jackman continued, “You can spot them coming a mile off, and they’re really unpleasant. And of course, they are – they’re still dangerous – but the ones that are very dangerous, are the ones who work their way into your affections and gaslight you.”

Galitzine seemed to understand the brief perfectly, crafting such a fascinating character study in the form of Manfred. “So many misogynists think that they love women. In some ways, he is more progressive than some men of his time, but ultimately, all roads lead back to protecting your own comfort and seeing women as a bit less human. And he thinks he’s really opening himself up, and in a way, he is, but the threshold is so low that the bare minimum feels huge.”

Pop icon Charli XCX also has a role in the film as Rosa, a woman whose story is told by Hero to Cherry. A lot of star-powered casting has been cropping up in cinema lately, but her role here doesn’t feel like a mere vanity project. After being put in contact by an agent, the pair met up, and Jackman soon realised how perfect she’d be to play this mythic vision of a woman told through story. “While we were speaking about what had chimed with her about the script, I really saw her as Rosa. She was really thoughtful and funny and dry.”

So, with her cast assembled and a dedicated vision of how she wanted to explore queerness and gender with both humour and poignancy, Jackman had to conjure up the perfect visuals to bring this fairytale to life. She looked at films like Sally Potter’s Orlando, “which had that slightly surreal feel and that sort of gender queer feel,” and Yorgos Lanthimos’ recent Oscar winner Poor Things, although she wanted “it to feel more femme and grounded in emotion, like [Celine Sciamma’s] Portrait of a Lady on Fire.”

While there’s a timelessness to the film, Jackman and cinematographer Xenia Patricia were inspired by techniques used in bygone cinematic eras. “We ended up using quite a lot of zooms, which are a camp quality to some of those ’70s folk horror films, but it can also be quite delicate and affecting.”

Paintings and architecture were big references to, including stained glass. “I knew a long time ago that I wanted stained glass to be a big element in this,” Jackman says. “So, looking at religious iconography, exploring the colours that light made when refracted through stained glass. I’d said very early on that I wanted the lighting to feel like it could be through stained glass, which I think led to the more colourful lighting.”

100 Nights of Hero is a visual feast, the aesthetic choices anchoring the film in a world of whimsy that contrasts the darker thematic elements of the narrative, and Jackman’s film, which explores pertinent themes like female literacy and heteronormativity, might exist in some fairy tale world where magic can happen, but there’s nothing fictional about the issues at hand.

With a considered and artful eye, Jackman has made a film that speaks of resilience and fulfilment, framed by the most surreal and phantasmagorical visuals you can imagine.

[embedded content]

Related Topics