The movie Orson Welles said gave him all the education he needed: “I’d learned whatever I knew”

Posted On

Posted On

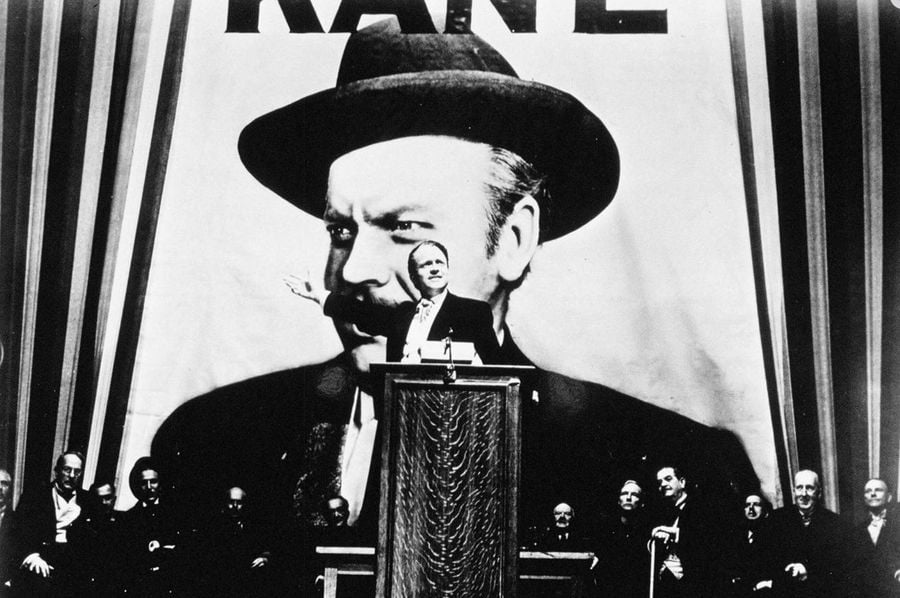

(Credit: RKO Radio Pictures, still photographer Alexander Kahle)

It is a tired cliché at this point to lavish Orson Welles with superlatives, and these days, film scholars have become a little more expansive in their criteria for what makes a great auteur. But there is no denying his inventiveness and influence behind the camera. He helped standardise the practice of using camera angles to express emotion and pioneered the use ofdeep focus.

As with any filmmaker working after the dawn of sound, Welles wasn’t just inventing techniques out of thin air, he was drawing on the work of other directors and expanding on their innovations. He was a fan of the German Expressionists, which is evident in his prolific use of light and shadow, but more than anything else, he got his ideas from the Irish director John Ford.

Known for his many collaborations with John Wayne, Ford helped transform the western from low-budget, B-movie territory to a prestigious genre with the same amount of depth and complexity as the most cerebral social drama. The film that started it all was 1939’s Stagecoach, a simple story about a group of strangers travelling through the Old West in a stagecoach, only to find themselves under attack by Apaches.

It was John Wayne’s breakout role as a movie star. Playing a young outlaw named Ringo Kid, his easy charisma leaps off the screen. But it’s Ford’s masterful direction that holds your attention. Despite having carefully-placed, breathtaking action sequences, Stagecoach draws you in through character development. Why are all these disparate characters – an outlaw, a pregnant woman, a sex worker, a banker, etc. – travelling through such notoriously dangerous territory? And how will they organise themselves as a group to withstand the threats from outside and within the stagecoach itself? The answers unfold slowly, and the director gives each character their moment to shine. There isn’t a single protagonist. It’s an ensemble film. And as an ensemble, the actors work as an organism.

From a technical standpoint, Ford was also pushing the envelope, using low angles, placing a camera angled upward from the ground to make it appear like horses are trampling the lens, and juxtaposing the confines of the stagecoach with the vast expanse of Monument Valley.

Welles was in awe of the film. He claimed to have watched 40 times to prepare for making his debut film, Citizen Kane, the year after Ford’s movie was released. “As it turned out, the first day I ever walked onto a set was my first day as a director,” Welles said once. “I’d learned whatever I knew in the projection room – from Ford.”

The fact that the young director watched the film dozens of times is even more remarkable, considering that he often cautioned emerging filmmakers about watching too many films. To him, a director needed a clean slate to be able to create from their own imaginations rather than simply creating homages to other directors. Stagecoach was clearly an exception, and though Welles clearly drew inspiration from the film and used it as an education in cinematic language, he developed a style all his own.

[embedded content]

Related Topics