Do we live inside a parody? Samuel Beckett’s 40-second plays and the perils of social media

Posted On

Posted On

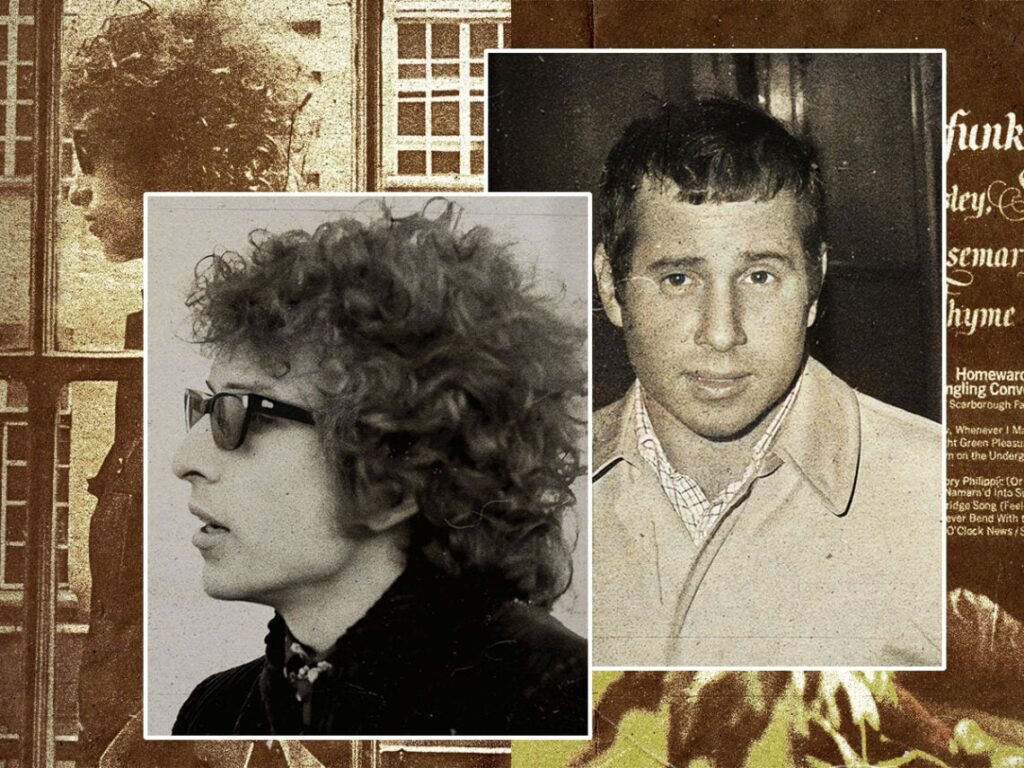

(Credits: Far Out / MUBI)

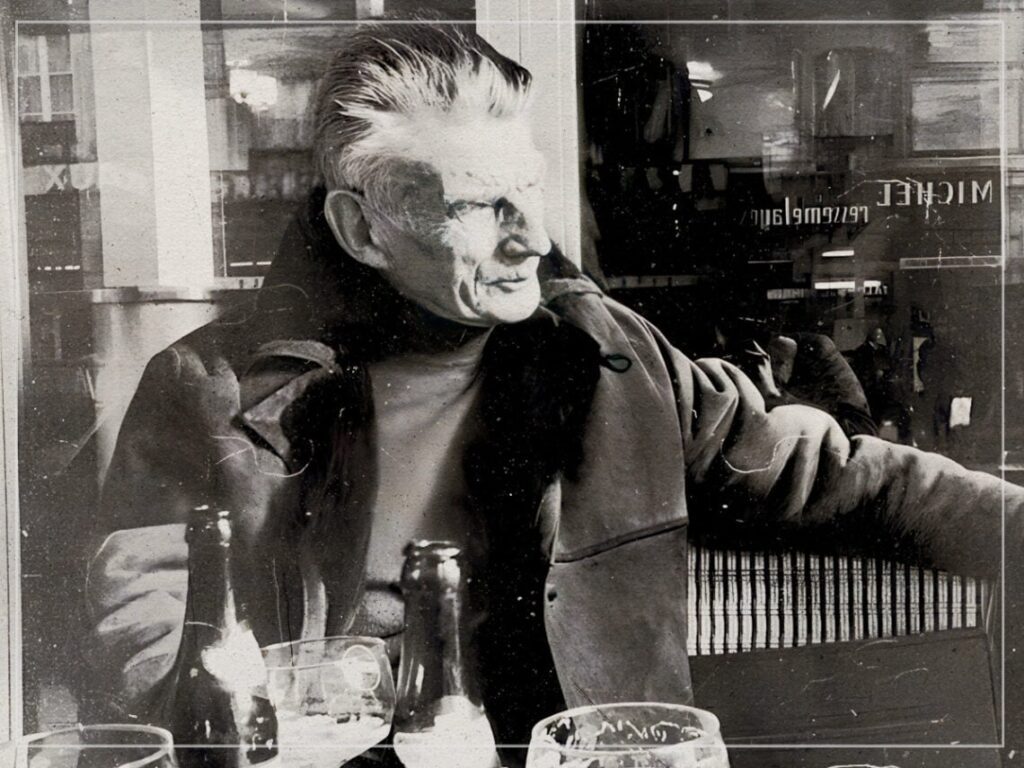

Samuel Beckett once said, “Every word is like an unnecessary stain on silence and nothingness.” In essence, if you are going to write, speak, or create something that desires the attention of others, it should receive due care and attention. This should always be the case with the creative world, but as our access to art increases, it seems the quality plummets at an equal rate, to the point that it’s almost as if we are living in one of Samuel Beckett’s parodies.

When you consider many different art forms, for instance, if we see a film we love, a picture that moves us or listens to a song we enjoy, we don’t believe that we have exhausted our experience with that art after being exposed to it once. When you listen to ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ by Queen, you don’t think your journey with the song is complete—quite the opposite. You get excited about engaging with the art again, analysing why it moves you and what various sections of the track likely mean.

The fact that art can be consumed repeatedly and that consumption only heightens its stature rather than diminishes it provides interesting insight into the artistic world. Specifically, the function of the audience or consumer is as important as the function of the artist and producer. Essentially, we, as consumers, play a much more significant part in the creation of art than we think.

Because of an artist’s strange connection with a consumer, the amount that we admire art can be equal to how much we require it. Speaking quantitatively, the more people who are exposed to a piece of art, the greater the potential impact of said art is. Equally, in qualitative terms, the consumer can impact the art by involving themselves in the process.

Artists are well aware of how big a part the audience can play in their work, and that’s why many artists approach a work with the audience in mind rather than themselves. Not only do artists do this, but those involved in the mass production of art do as well. They don’t use art as expression; instead, they think about what the audience will most likely engage with and run with that idea.

Pair this with the ease of access that we now have to art. We don’t have to go to a record store to buy an album; we don’t have to go to the cinema to watch a film; we don’t have to; we don’t even need to leave our house to socialise and engage with the communicative aspect of art. Everything is available on our phones and our TV screens. Slowly, art has moved from something the artist creates and the consumer engages with to something that the consumer will engage with and that an artist can facilitate the creation of.

In the face of increased production and consumption, the risk that artists face is the idea of their work becoming a commodity, something passive that we consume with no real appreciation. The best way that an artist can ensure their work doesn’t become a commodity is to create something that continues to require active participation from an audience. This means pieces of work are now being left unfinished and incomplete until something else is added by those who would previously just consume. A song has to go viral; a video needs comments. People capitalise on the human nature of rage, love, sadness, whatever will garner a response, and use it to ensure their art reaches a large audience and becomes more of an achievement in the amount people respond to it, regardless of how negative or positive that response is. We judge a piece based on how many streams it has as a sign of merit as opposed to the actual piece itself.

The two things that are crucial to ensure that people will react to something created are an emotive response and a short enough view time that somebody who has access to the whole world at their fingertips will remain engaged. People post a 40-second clip of a song they know is bad to get angry consumers commenting and, in turn, boosting appeal. Poorly acted videos intended to garner fury are chopped down to 45 seconds to make people watch and make them lash out in rage. We live in an age where disapproval of art adds to its approval. We live in an age where outrage is an economic commodity. We live in a time of parody.

The Dada movement of the 1920s was a period that championed parody, revelling in the abstract as a means of highlighting absurdity. The depressing point is that we seem to be living in a reimagination of the Dada movement, but one that takes itself completely literally. The 40-second plays and ten-page novels created by Samuel Beckett are reborn in the form of social media clips and comments. While people would engage with these works of Beckett, understanding that they are supposed to be abstract, we now engage with short, low-quality pieces of art as our primary means of consumption.

It’s tough to know what the solution is. While some may argue that it is in the nature of art to progress with the times, it also feels disheartening knowing that change comes in the form of reduced quality and the shredding of genuine connection. Hopefully, at some point, this period of parody will be recognised for the laughing stock it is, but until then, while we continue to take it entirely seriously, the joke is well and truly on us.

[embedded content]

Related Topics