Adam Curtis once blamed Wes Anderson for delivering the “ideology of our day”

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Focus Features / Niko Tavernise)

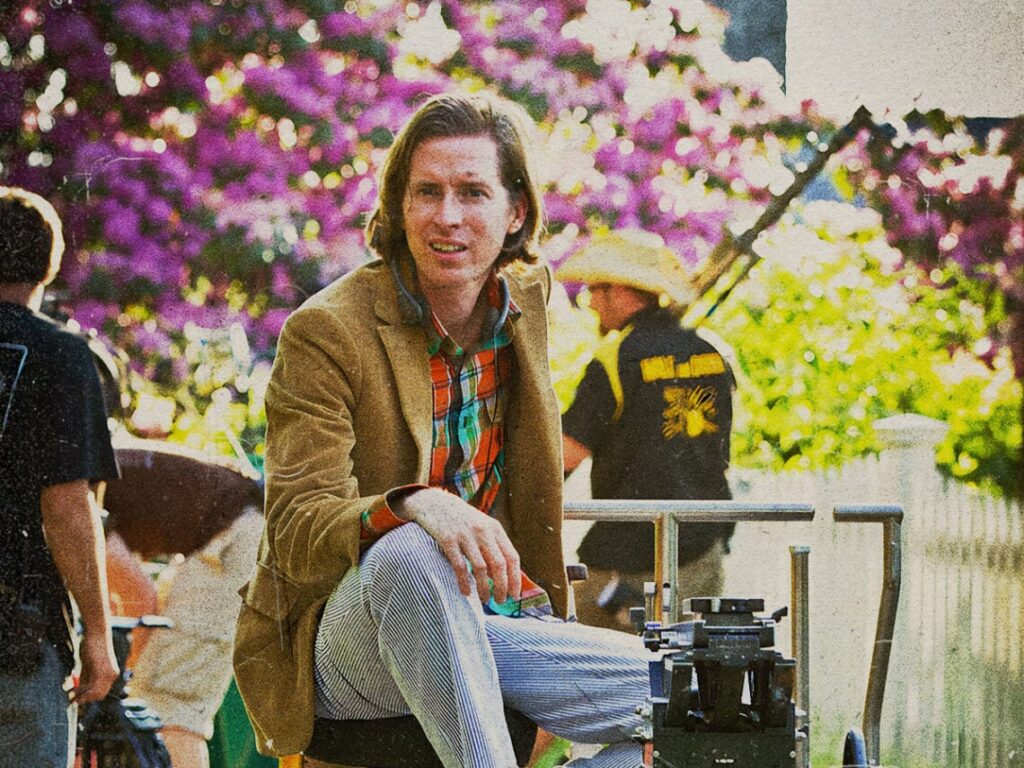

When gazing upon a movie by Wes Anderson, there’s no doubt in an audience’s mind that it is ubiquitously his own. After all, out of all the contemporary directors, Anderson’s visual style is perhaps the most recognisable, defined by a strikingly symmetrical and pastel-toned aesthetic.

Throughout the likes of Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Darjeeling Limited and The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson has established himself as a cinematic auteur, a master of film who frequently explores themes of family, grief and loss, always delivered in his trademark style.

That style is just about as far away as that of someone like Adam Curtis, the British documentary maker who weaves together messy collages of archival footage to examine politics, history, sociology and philosophy to try and explain our present human condition. Curtis’ films are rather bleak in tone, but they are important from a socio-political perspective.

In fact, Curtis once criticised Anderson for the way his films deliver an overly positive view of the world, although he did so with a generous punch of humour. Speaking with Film Comment, Curtis once pointed out how Anderson’s films can often “retreat into a pessimistic view that we’re just fixed creatures.”

“There’s nothing we can do,” he suggested of Anderson’s narratives. “Let’s just stay at home and have tea.” That kind of “keep calm and carry on” mantra is precisely what Anderson wants to “attack” with his films, to show that “you can change the world for the better,” even though we are “all fundamentally flawed creatures.”

“The person I really blame is Wes Anderson,” he explained. “There’s a bit in Wes Anderson’s film The Life Aquatic at the end where Bill Murray and the others all hold hands in a submarine and Bill Murray – I’m misquoting – utters Wes Anderson’s ideology, which is basically the ideology of our day: ‘We’re all a bit crap, but that’s okay.’”

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, released in 2004, saw Murray play an oceanographer who seeks revenge against a shark who ate his partner. As Curtis explains, there’s often a sense in Anderson’s characters that because they are flawed individuals, it’s okay to not seek out change, justifying the status quo, or as Curtis notes, “No one is better than anyone else, but we’re all crap, so there’s no point really in trying.”

However, that mantra is “so depressing and so dismal and such a low view of the world” for Curtis, who sees it as a “reaction to the failure of great attempts to change the world.” Still, the British filmmaker does not believe that one should abandon their efforts to change the world just because we are indeed flawed, which is something he believes Anderson inadvertently does with his movies.

Of course, Anderson’s movies are just about as apolitical as you can get, so it’s not as though he is dousing his work in an air of intentional ambivalence. Still, Curtis feels that the likes of The Royal Tenenbaums and The Life Aquatic have reinforced a selfish “ideology which encourages you to prioritise what you think and what you feel and what you want as the centre of the universe.”

The films of Curtis and Anderson are just as far apart in terms of their themes and aesthetics as you can imagine, but Curtis is so invested in the world of socio-politics that he finds a great problem in the overly cutesy style of Anderson, a criticism that hasn’t been levied against the American director on many occasions.

[embedded content]

Related Topics