The anti-samurai sentiments of Kaneto Shindo’s ‘Onibaba’

Posted On

Posted On

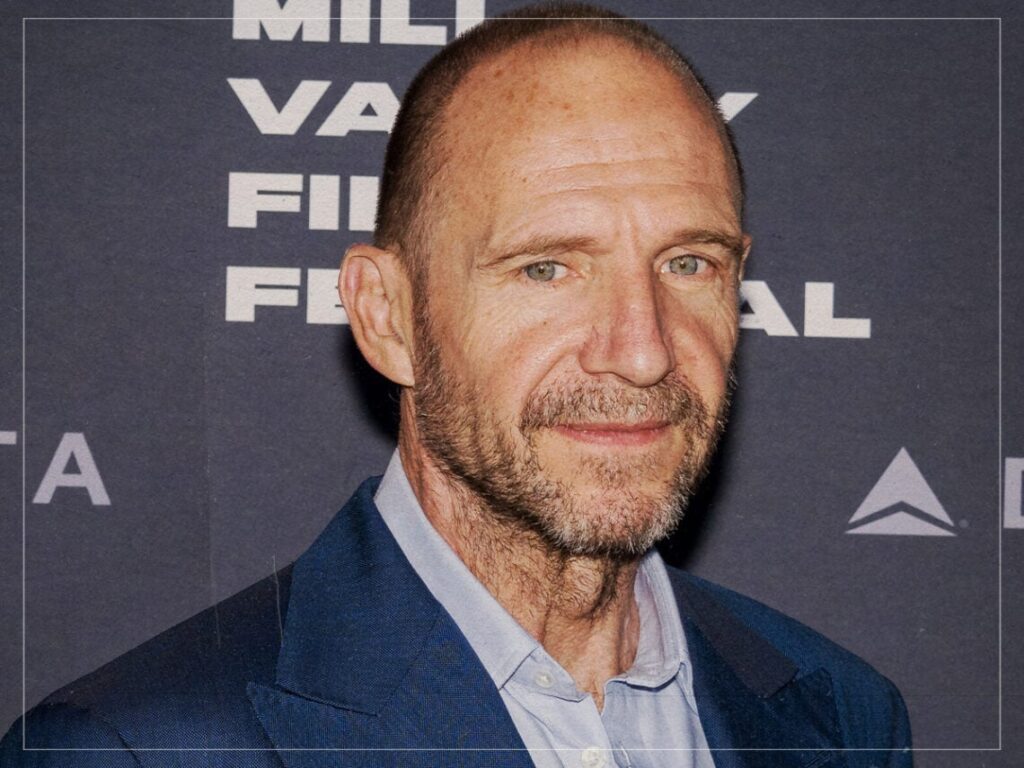

(Credits: Far Out / Toho)

The samurai genre is one of the most popular period drama categorisations in the cinematic realm of Japan, and early films in the genre were often dramatic in tone, while later works glorified the action combative action of the Tokugawa or Sengoku eras in Japanese history.

Focusing on the honour and code of conduct of a samurai or a masterless ronin, samurai movies often explored the psychological and physical effects of a life in solitary duty. While the works of Akira Kurosawa, Masaki Kobayashi and even Takashi Miike have drawn acclaim for their examination of samurai valour and honour, there’s a classic Japanese historical drama that serves as something of an “anti-samurai” movie.

Kaneto Shindo’s widely admired 1964 work Onibaba is this precise film. By straying from the commonly accepted tropes and conventions of the samurai genre, Shindo details the effects of warfare in the Nanboku-cho period, when conflict was rife and led to widespread social and political upheaval. However, through delivering, in essence, a horror story, Shindo eschewed the action of the samurai film and dived into something far darker.

Nobuko Otowa and Jitsuko Yoshimura play two peasant women who murder two soldiers fleeing from the Battle of Minatogawa and who subsequently sell their weapons and armour in order to survive. Onibaba, which translates to ‘Demon Woman’ in English, creates an eerie air of the supernatural, creating a departure from normal samurai movies, even more so than Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood.

Championed for its creeping atmosphere and intense cinematography that captures its minimalist setting, Onibaba is the work of a master. By using a field of tall grass and rundown domiciles as the film’s setting, Shindo leaves behind the battlefields of the samurai genre in favour of a focus on the relationship between mother and daughter-in-law and the merchant who fosters a mutual sense of resentment and jealousy in one another, showcasing the destructive nature of war on the peasantry without submitting to detailing actual military conflict.

Rather than depicting samurais as noble warriors with strong ethical codes of conduct, Onibaba suggests that they are oppressors of the common people. Shindo’s narrative has the two women deal with such figures in the most harrowing and violent of ways if only driven by a necessity to survive and to keep death, sickness, and starvation at bay.

It’s the horror and supernatural elements of Onibaba that really cement its position in the anti-samurai genre, though. The demon mask stolen from a murdered samurai becomes a symbol of the mother’s descent into psychological madness whereby the boundaries between human morality and otherworldly violence are blurred, offering the suggestion that war itself creates an inevitable psychological consequence on those who aren’t necessarily even a part of it.

The black-and-white cinematography, though, is very much in line with the great samurai movies of yore. However, this only serves to create a distinction between the narratives of such films and Onibaba itself, which possesses a unique sense of evil and dread, a far cry from the honour and valour found in the works of Kurosawa and Kobayashi.

Onibaba is a masterwork of Japanese cinema, one that transcends the conventions of one of the country’s most popular genres. By removing the romantic qualities of the samurai’s narrative, Kaneto Shindo details the brutal realities of war on those most often banished from its most famous stories.

[embedded content]