Pioneering independence: 10 modern movies inspired by the Italian neorealism movement

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Searchlight Pictures / MUBI / BFI / The Works)

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the Italian neorealism movement of the late 1940s and 1950s had such a profound effect on the shape of cinema in the latter half of the 20th century. Donned “the most precious moment in film history” by the great Martin Scorsese, cinema’s focus on the working man and woman would continue long into the century thanks to the movies of Federico Fellini, Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica.

The French New Wave era of creativity and innovation in the 1960s was one era of cinema that was particularly influenced by neorealism, with the likes of Agnès Varda, Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut each taking direct influence from the stark styles of the Italian pioneers. In turn, this led to the emergence of New Hollywood in the late 20th century, where such minds as Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Robert Altman drew from the exciting work of the New Wave minds.

As Giulia Saccogna, the programmer for the BFI’s latest Italian Neorealism season, points out, the movement encouraged a global domino effect in cinema. “The list is very long, but just to mention a few: Luis Buñuel, Satyajit Ray, Ousmane Sembène,” she said of contemporary directors who have been inspired by neorealism, adding, “Cinema Novo in Brazil, the Third Cinema in Argentina, Free Cinema in Britain, Neorealism Iranian style, New Hollywood Cinema, but also more recently Kelly Reichart, Ken Loach…In short, it has always been ingrained in the fabric of independent arthouse cinema”.

Taking the spirit of the movement and modernising it for contemporary audiences, the following movies have a debt to pay to Italian neorealism.

10 contemporary movies inspired by the Italian neorealism:

After the Storm (Hirokazu Koreeda, 2016)

It’s no secret that Hirokazu Koreeda has been championed as one of the greatest modern Japanese filmmakers, but his 2016 film After the Storm is one of his most underrated gems. Telling the story of a private detective trying to reconnect with his son and ex-wife following the death of his own father, Koreeda’s film plays on his long-held interest in family heritage and how love is passed from one generation to another.

While the story of the film takes notes from neorealism, it is the style of After the Storm which is most influenced, with Koreeda saying of the Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini: “Fellini has been a very strong presence in my life, since I was only 16. My first choices as a director were influenced by him. He gave me a clear idea of what directing is and its meaning. Fellini had a duplicitous aspect, caught between character and poetry”.

[embedded content]

Daddy Longlegs (Josh Safdie, Benny Safdie, 2009)

Speaking of directors who are directly inspired by the work of Italian neorealism, each of the movies of the American Safdie brothers feels stripped from the very core of the works of Vittorio De Sica. Naming the 1948 classic Bicycle Thieves as one of their all-time favourite movies, the influence of neorealism isn’t hard to spot in their work, with their 2009 film Daddy Longlegs being one of the clearest examples, telling the story of a father trying to cope with his own life while raising his children at the very same time.

Laced with comedy and heart, Daddy Longlegs feels like an American interpretation of Italian neorealism, with the distinctive style of the movement being replicated here with 16mm and Arriflex 416 cameras that shake and sway as if it were being filmed ad-hoc in real life. Using non-professional actors or performers to make their feature film debut, the Safdie brothers created a movie that was authentic and passionately raw.

[embedded content]

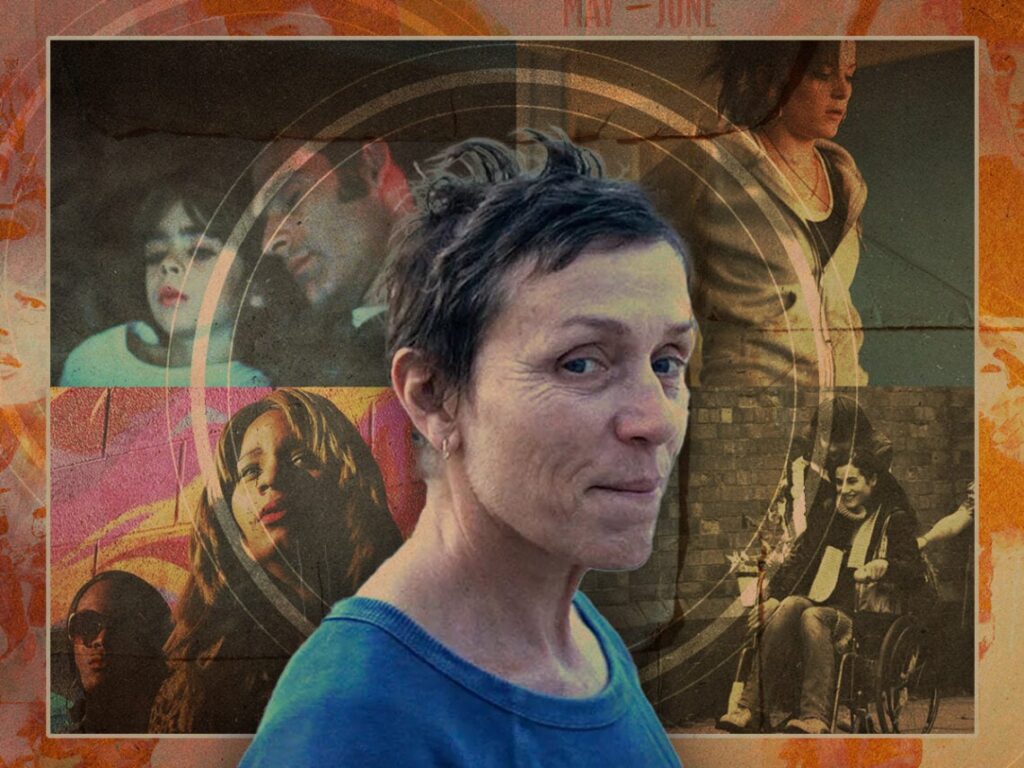

Fish Tank (Andrea Arnold, 2009)

Lovers of social realism, the fingerprints of Italian neorealism, can be found throughout the history of British cinema, with the 2009 film Fish Tank by Andrea Arnold being no different. Telling the story of an isolated young girl living in an East London council estate whose world is upended by the arrival of her mum’s new boyfriend, Arnold’s film is a powerful study of the adolescent experience from the viewpoint of an underrepresented cohort of people.

Recruiting Katie Jarvis, an actor with no previous acting experience, in the lead role, Arnold forges a narrative that reflects the authenticity of the British capital in the late 2000s. Taking on social realism with a dedication to poetic storytelling, Fish Tank remains one of her finest movies.

[embedded content]

Gomorrah (Matteo Garrone, 2008)

It wouldn’t feel right to make a list of modern movies inspired by neorealism without delving into contemporary Italian cinema. Released in 2008, Matteo Garrone’s Gomorrah, based on the book of the same name by Roberto Saviano, the film depicts the real-life crime syndicate, named the Casalesi clan, offering a remarkable insight into the lives of abhorrent criminals, differing from the ‘salt of the earth’ characters of traditional neorealism.

Certainly not a typical neorealism tale, Gomorrah does share similarities with the post-war movement, especially in its frank approach to its visual style. Capturing sound live on location, Garrone also used real locations and hand-held camera work to capture the authenticity of the gritty tale.

[embedded content]

George Washington (David Gordon Green, 2000)

Modern independent American cinema, with its minimalism and commitment to low-budget filmmaking, has long drawn comparisons to the neorealist films of post-war Italy. For example, David Gordon Green’s 2000 film George Washington, which became an indie hit of early 21st-century American cinema, felt stripped from the neorealism playbook with an extra sprinkling of enchanting authenticity.

A bleak coming-of-age tale about a young boy and his group of friends who mistakenly kill someone during summer in a small, downtrodden town, George Washington has all the hallmarks of neorealism. With the humanity of his central characters front and centre, Green also commits to stylistic minimalism, recruiting non-professional actors to help him achieve this.

[embedded content]

Man Push Cart (Ramin Bahrani, 2005)

The forgotten American indie movie Man Push Cart, directed by Ramin Bahrani, is so indebted to Italian neorealism that the legacy of Rossellini and De Sica runs through its DNA. A film about a Pakistani immigrant who goes about selling coffee and doughnuts on the streets of Manhattan, Bahrani focuses much of his efforts on curating a distinctive style for the film, which bleeds with sheer love for the human race.

The beauty of Man Push Cart is, indeed, in its simplicity, something which neorealism was championed for. “I like those films because they deal with reality,” the director told Reverse Shot, “I’ve always been interested in reality and I’ve always been terrified of escape. I don’t like escape in my personal life or in my art, and I prefer to try to understand how I should behave in this world based on what’s really around me. And I try to do that with my eyes open to the best of whatever knowledge I have, which is finite—I don’t know everything.

[embedded content]

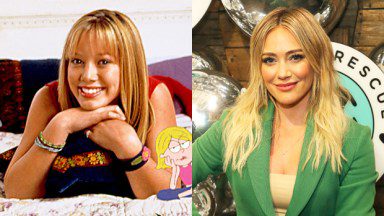

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao, 2020)

Few filmmakers are as influenced by the pioneers of neorealism as American director Chloé Zhao, whose entire filmography breathes from the same body of work that thrived in post-war Italy. Her 2020 ‘Best Picture’ winner Nomadland is certainly her masterpiece, with the film using real-life locations, non-professional actors and a stark documentary style to tell her deeply human story of a woman who abandons her city life after the financial crisis to live and travel in the wild.

Taking note from Rossellini, Zhao’s 2017 film The Rider is similarly dedicated to realism above all else, yet Nomadland has truly stood the test of time. An innately human tale that ties itself by holding up a mirror to the questionable contemporary world of consumerism, Nomadland does neorealism proud.

[embedded content]

Somers Town (Shane Meadows, 2008)

The world of British social realism has already been touched on earlier in this list when the virtues of Andrea Arnold were sung, but arguably, no one does it better in Britain than Shane Meadows. Transforming modern independent British cinema with his style of filmmaking that champions authenticity, in Meadows’s films, characters talk over each other, pause for extensive periods of time, and have their own idiosyncratic inflexions, giving each one a life and soul of their own.

He may have better films, but no release better reflects his influence of neorealism better than 2008’s Somers Town, a monochrome film that follows two unlikely friends who explore the streets of urban London. An innately human approach to filmmaking, Meadows adds few frills to his work, often using non-professional actors in his tales that focus on people surviving on the fringes of society.

[embedded content]

Tangerine (Sean Baker, 2015)

The services of American filmmaker Sean Baker to contemporary cinema have been unparalleled, yet he has only recently received his due plaudits, winning the Palme d’Or in 2024 for Anora. While he loves a sprinkling of magical realism, Baker is also committed to telling authentic stories about America’s most curious estranged souls who are struggling to live from month to month.

While each of his movies shares this similarity, 2015’s Tangerine is the piece of work that best reflects Italian neorealism, telling the story of two sex workers in LA trying to seek justice on Christmas Eve. Shot on an iPhone, Baker’s film is dedicated to its independent roots and to its promise to reflect the true lives of its subjects, even if it does so with an ingenious eye for comedy.

[embedded content]

Wendy and Lucy (Kelly Reichardt, 2008)

Independent American cinema has been a recurring theme on this list, and the final entry is no different, with the movies of Kelly Reichardt bookending this collection. Indeed, while Wendy and Lucy might be the director’s biggest tribute to the world of Italian neorealism, almost each and every one of her films owes a debt to the post-war style in their focus on humble, human souls trying to find solace in times of tough societal pressures.

Released in 2008, Wendy and Lucy, which told the story of a woman and her dog whose lives change forever as a result of the financial crisis, Reichardt said of the movie which shares many similarities to Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D: “That film is a masterpiece. What can you say about that movie?…They also sort of touch on themes like, are we connected? How much should we be helping each other out? Those kinds of questions”.

[embedded content]