The Lars von Trier movie that depressed Rick Rubin for three months

Posted On

Posted On

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

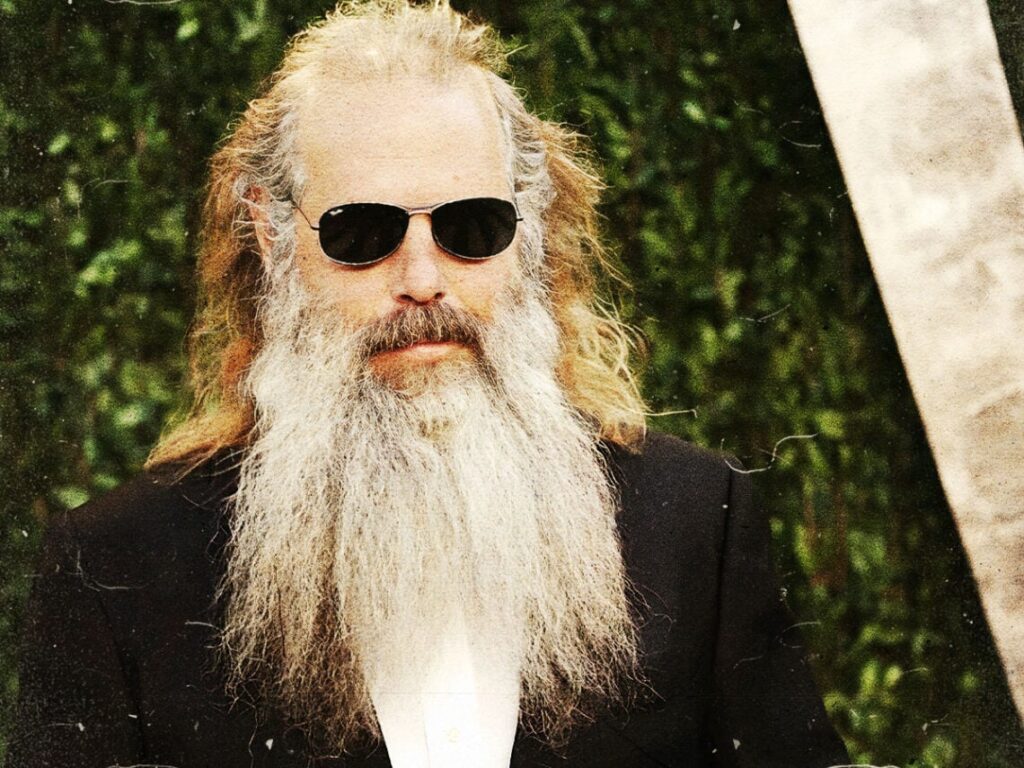

A sheer monolith in the music industry, the legendary producer Rick Rubin has proven throughout his career that he possesses a deep ability to bring the best out of the artists he works with. With a refined technical ability and a profound understanding of the actual process and reality of creativity itself, Rubin has carved out a legacy that speaks for itself.

By employing a minimalist approach to production, Rubin has been able to get to the essence of a song, which has been considered attractive to some of the biggest recording artists in the history of music, including Jay-Z, Johnny Cash and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, the likes of which also showcase a versatility for style and genre that so many other producers could only ever dream of achieving.

As a bastion of creativity, Rubin’s love for artistic endeavours extends far beyond his usual realm of music. The producer once explained how the cinematic medium can have a deep impression on his mood and psyche and pointed out a Lars von Trier movie that left his spirits increasingly low.

“A movie can impact me,” Rubin once admitted. “Like there was a movie called Melancholia that I saw years ago, a Lars von Trier movie. I thought it was a very beautiful movie, but I was in a bad mood for, I would say, three months from the time I watched that movie onwards. It just like did something to my brain that didn’t feel good. I couldn’t snap out of it.”

Well, it’s no wonder that Melancholia left Rubin feeling melancholy for so long as it’s the middle part of von Trier’s Depression Trilogy and centres on the very experience of mental affliction. The Danish director likens depression to an impending global disaster, and the film sees Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg play two sisters who experience anxiety and melancholy in starkly different manners.

The recently married Justine seems to have complete apathy towards the events that surround her, even as a rogue planet inevitably hurtles towards Earth. However, Claire, who tackles life with a more rational approach, can’t accept such a truth and writhes in angst and desperation of the unavoidable.

Many consider the film to be amongst von Trier’s best work and informed by his own experiences with anxiety and depression; it certainly does a commendable job of detailing the kind of low-mood moments of our lives, aided by some of his best cinematography and a score that haunts the images with which it co-exists.

It’s understandable, therefore, why Rubin would have felt such a great impact after watching Melancholia, a film that shudders one’s emotions and senses to the core simultaneously. Of course, though, the film has more resonance with those who have themselves experienced depression and also those who have a higher level of emotive sensitivity, as Rubin clearly does.

Rubin has often spoken openly about his struggle with depression and once told Lex Fridman, “When I went through depression, afterwards, I was a different person than I was before. And I feel more grounded now than I did then, and I probably relate to the artists – so many of the artists I work with suffer – so many artists suffer because that’s part of what makes an artist great: their level of sensitivity.”

[embedded content]

[embedded content]