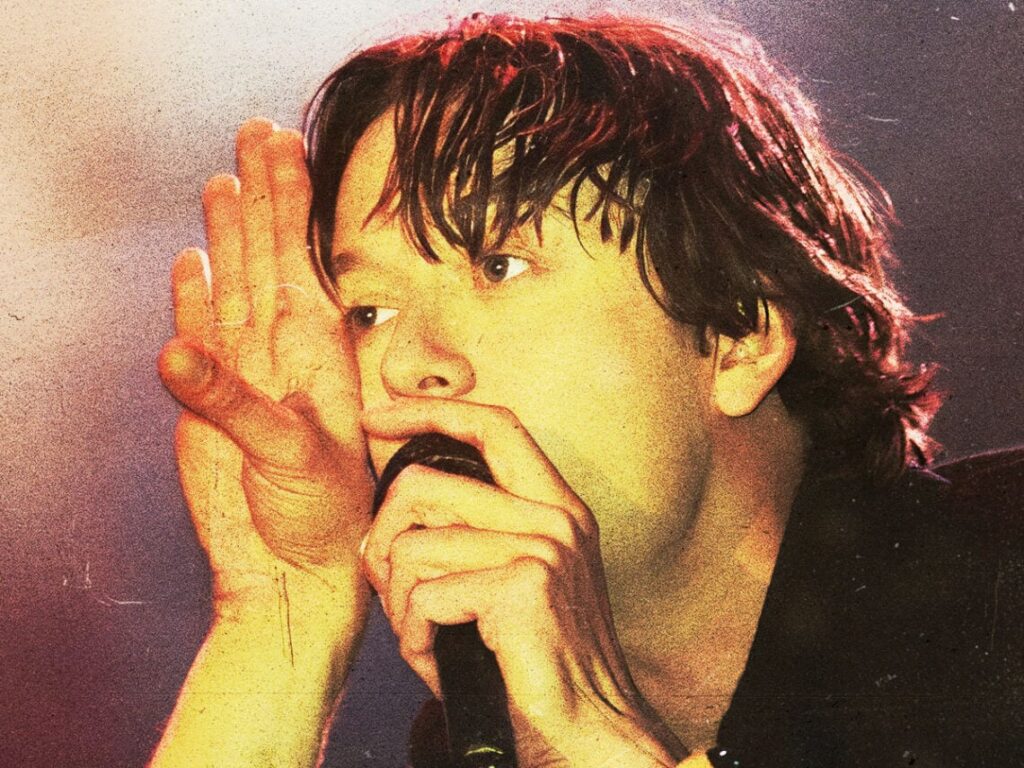

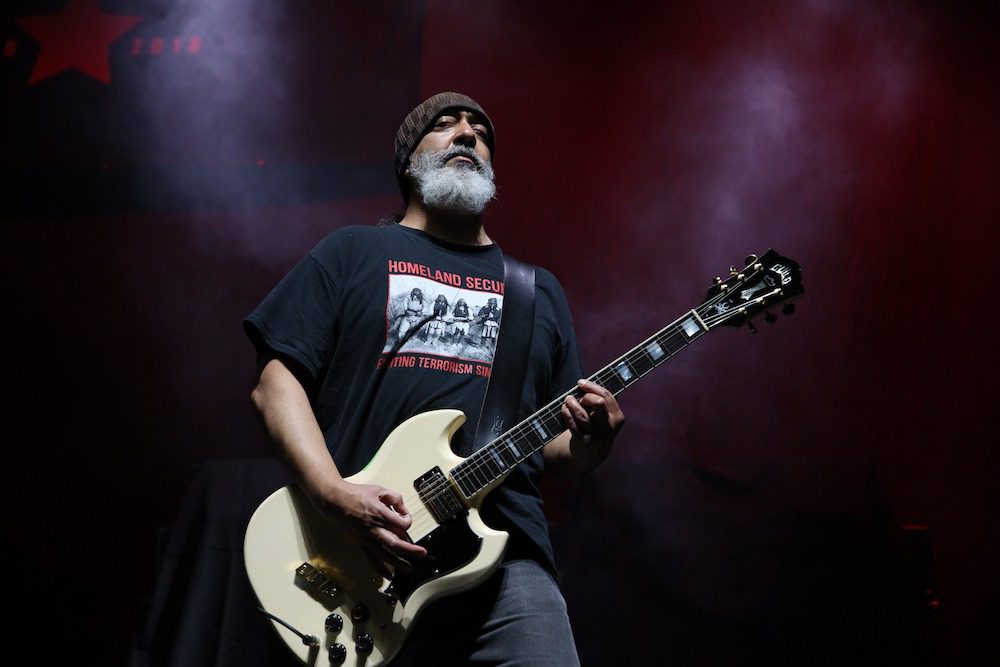

Soundgarden's Kim Thayil on Protests, Quarantine and Teaming Up With Brandi Carlile

Posted On

Posted On

Like most of us, Kim Thayil has spent the past few months more or less sheltering in place.

Which, by his own definition, might not be something particularly out of character for the 59-year-old Soundgarden guitarist. “So many of the people I know who are writers and players, if they’re not the kind of person that jumps around and parties all the time, tend to live as hermits to begin with,” he says, calling SPIN from his Seattle-area home.

But while Thayil, whose dense, twisted-metal riffs and noise-damaged, often frenzied solos belie his generally reserved public demeanor, would likely never be perceived as the jump-around-and-party type, he has managed to remain fairly active while also staying home and doing nothing much at all.

“I think a lot of this shelter-in-place thing has really been about focusing on the big picture — what’s going on in society, what’s going on in our community, what’s going on in the country. There are a lot of big political and social issues,” he says. “And then there’s also the small picture, like, how do I manage to address my domestic needs? How do I connect with family and friends?”

For Thayil, the solution has been to spend his days engaged in both major and minor activities. He’s listening to music, “farting around” on the guitar and, like the rest of us, ordering stuff on Amazon and learning how to use Zoom. At the same time, he has participated in the rallies and protests that have gripped cities like Seattle in the wake of George Floyd’s murder. “One of the amazing things about this time right now is how one social and cultural issue flowed into another important one,” he notes. “These protests may not have happened in the first few weeks of the COVID-19 shutdown, but they also may not have happened without a COVID-19 shutdown.”

Thayil took some time to talk (and no, not over Zoom) about sheltering in place and protesting in the streets, and the motivations and outcomes attached to these actions. He also spoke about the musical activities that have been filling his quarantined days, from anticipating a Record Store Day release that sees the surviving members of Soundgarden — Thayil, bassist Ben Shepherd and drummer Matt Cameron — backing Brandi Carlile on two of their own songs, to immersing himself in the pleasures of deep-net music scavenging.

To that last point, he enthuses, “You’re home, someone texts you a link to some weird digital electronic version of Black Sabbath’s ‘Paranoid,’ it gets a laugh out of you and then you send it onto someone else and they send something back,” he says. “That kind of conversation wouldn’t only occur during this weird COVID-19 shutdown time, but it certainly is more likely to. It’s like, ‘Oh, look—this guy programmed a bot to invent an AC/DC-style song!’ You send out the link, and the next thing you know people are turning each other on to weird stuff. That’s the kind of conversation that I’ve had with musicians and writers over the past couple of months. And that’s been a great thing.”

SPIN: So what has quarantine life been like for you these past few months?

Kim Thayil: It’s been very mellow, just watching the zombie apocalypse—you know, the empty streets with a few walkers. It’s kind of like living your life like you don’t exist. [Laughs.] I learned how to do the Zoom. I had some Zoom calls with family and with band family as well, some of our crew guys. So that’s been fun.

Has there been any music happening on your end?

I’ve had a lot of offers come at me. A lot of friends are writing or trying to record things and doing things remotely. I actually shot a video remotely. You know Brian Posehn, right? He’s a big metal fan and he just released an album, Grandpa Metal, sort of a heavy-metal-comedy thing. I play a couple of solos on the title track, and there’s some work we did on a video for the song, where everyone recorded cellphone footage from their own shelter and then we emailed the footage to each other.

Have you been writing on guitar at all?

You know, it’s odd because the situation I’m in right now does not provide access to a home studio set up. But for me, every time I pick up a guitar I usually come up with something. Because of the way I play, I wasn’t formally trained. I don’t run through scales. And so I end up writing things. That’s fortunate, I suppose. I just start farting around and I come up with something interesting that I like and then I try to remember it.

Soundgarden and so many of your Seattle contemporaries emerged out of an incredibly fertile and close-knit scene. Do you believe that sort of music community will, or can, exist again once we’re through this pandemic?

I would hope so. Those are conversations I’ve certainly had with many of my peers and friends over the past number of months. As far as a sentimental attachment, there is support for the community and for various venues, but all of us have also been around so long that we’re used to venues disappearing. You know, Soundgarden used to play at the Rainbow Tavern, which has quite a history in Seattle, and that’s been gone since, I don’t know, the ‘80s, early ‘90s. The Central Tavern hasn’t really booked bands like they used to in their heyday, and the Moore Theater still has national acts and big local acts, but I don’t know how they’re doing financially, whether they can weather the storm.

But over the past 30, 40 years, things have always shifted in Seattle. Whether it’s the U District or Capitol Hill or downtown, wherever you can find affordable rents and artist studios, that’s the district that becomes the base for up-and-coming and indie bands. I think it’s like that in every city. So I hope we’re able to weather it. But there’s definitely going to be some skeletons and abandoned vehicles by the side of the road here when everything starts going again.

At the same time that people are at home sheltering in place, they’re also taking to the streets and protesting racial injustice in massive numbers.

I was involved in attending some protests early on in downtown Seattle. And there were definitely some negative consequences to what was a peaceful rally and issue—usually violent behavior on the part of, you know, either some disaffected demographic or criminal element or the cops. I mean, tensions run high and cops do stupid things. Also, there’s a component of most protests or demonstrations that gets some people’s fucking boners going and they get rowdy. And then there’s a criminal element which tends to exploit the cover that a political rally or peaceful protest might provide to them. That’s a bummer when those things happen, and unfortunately, it makes some of the concerns sort of change. But this is a great moment for people to address this issue, and also to help give a voice to some others who perhaps haven’t felt that they’ve had the opportunity or the ability to speak.

As a second-generation American and a person of color, how have you absorbed some of the issues—racism, police brutality—at the core of these protests? What has been your American experience?

My folks came here [from India] in the late ‘50s, and I was born in Seattle in 1960 and then raised in Chicago. It complicates one’s identity, being the son of an immigrant and then growing up very American. I mean, I look at my loves and they’re so distinctly American, from baseball to comic books to rock ‘n’ roll. But at the same time, there’s an important allegiance to an immigrant identity that I see with uncles, aunts, cousins, my grandparents. There’s the kind of values that are instilled in you in terms of education and things like that that add to the greater culture as a whole.

Now, a sub-component of being an immigrant is being a minority. And, obviously, I’m not an immigrant from England or Australia or Sweden. [Laughs.] So the minority element is an important part of my identity. Growing up I was certainly used to getting sideways looks from the police—not just as a brown guy, but as a long-haired brown guy. And growing up in Chicago, it’s incredibly metropolitan. It’s incredibly cosmopolitan as well. But at the same time, there was ridiculous segregation. You had areas that were very white, areas that were very black, areas that were very Hispanic. And I’m none of the above, right? I think more often than not, white people and black people thought I was Hispanic. Because they just didn’t know that many Indian people.

Would the police hassle you?

You know, you get looks…it’s a weird thing. I was never doing anything wrong when I was hassled by cops. The only time I would get hassled was when everything was clear and clean. But if I was involved in any juvenile hijinks? Suddenly there were no cops around. [Laughs.] But I generally didn’t get into much more trouble than any teenage stoner in the ‘70s would have gotten into. I was a good kid who was good at math and science…but I also liked rock ‘n’ roll and vodka.

So you were well rounded.

[Laughs.] Yes, I was well rounded. It’s so funny—I meet people from my past, from the town I grew up in, who characterize me as the long-haired kid with ripped-up jeans and who thought I was a delinquent. And then I meet other kids who are like, “Dude, you were the brainiac in chemistry class. We thought you were going to be a scientist or a doctor or something!” It’s like, “Wow, I guess you’re a lot of people when you’re growing up…”

To get back to music, have there been any particular artists or albums soundtracking your quarantine time?

You know, my girlfriend and I actually bought a turntable from Amazon and we were like, “Well, what records should we order?” And we went for the big sellers. Things like Dark Side of the Moon. Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours. The Eagles’ Hotel California. We were laughing about that. They’re just those albums where top to bottom it’s like, “Oh, I know this song. Well, I know that song.” Every song is something familiar and reminds you of when you were younger.

Musical comfort food.

[Laughs.] It feeds the nostalgia thing, which is kind of perfect in some ways while you’re in a shutdown. But the album that’s gotten the most airplay at my place has been John Coltrane’s Blue Train. I play that while washing the dishes. I play that while reading.

As far as vinyl is concerned, you and your Soundgarden bandmates recently teamed up with another Seattle-bred artist, Brandi Carlile, to record “Black Hole Sun” and “Searching With My Good Eye Closed” for an upcoming Record Store Day release. How was it to hear Brandi sing those songs from your past?

It was amazing. She nailed both songs, but “Searching With My Good Eye Closed,” there’s this thing her voice does in the verse… I don’t know how to describe it, but it just evokes tears. It’s really moving and beautiful. It’s strong and vulnerable. It’s fragility and power. It’s a small move but it kind of made the song hers.

I guess I can describe things this way: There are certain performances that I’ve seen or heard that have sent shivers up my spine. Chris [Cornell] certainly did that for me. The first time I saw Eddie Vedder sing with Mookie Blaylock. Jeff Beck doing the Beatles’ “A Day In the Life” instrumentally. It’s so moving that your eyes well up and you get that shiver. Brandi’s performance of “Searching With My Good Eye Closed” did that for me, too. That’s the power of music.